By Susan Tweit

When I was a child, I knew exactly where home was: Wyoming. Although I was born and lived in Illinois, I recognized the home of my heart on a family vacation. It was June, the beginning of one our annual weeks-long camping and nature study expeditions through the West.

My father was driving, gas pedal to the floor as he urged the engine of our home-made camper-van to its top speed on brand-new Interstate 80 west of Laramie. My mother, chief navigator, sat next to him, my brother scanned the passing landscape for birds new to his life list. I sat in back with my face buried in a book.

As the van engine knocked hard, I looked up. Elk Mountain, still splotched with spring snow, rose out of an ocean-like expanse of sagebrush, silver-green and spangled with moisture. The air pouring in the open jalousie windows bore a fragrance I still find intoxicating: turpentine mixed with pine-resin and the spicy sweetness of orange blossoms.

Sagebrush, I said to myself. I’m home.

My heart swelled with feelings a child could not explain.

Ever after, when asked where I was from, I answered without hesitation: “Wyoming.” My parents were chagrined, but it was clear to me: I simply existed in Illinois for the school year; home was the landscape my heart recognized, where sagebrush perfumed the air and mountains lined the horizon.

I moved to Wyoming in college, found a job in Yellowstone National Park, and never looked back. I got my first job as a field ecologist in Wyoming, wrote my first scientific publications there, married for the first time, divorced, married more wisely the second time, and wrote my first weekly newspaper column there, beginning my evolution into a writer who chronicled the lives and loves of the landscapes I called home.

When Richard, Molly, and I left of Wyoming one August evening nearly thirty years ago, bound for West Virginia and his first faculty position, I cried as I said goodbye to that wide landscape of sagebrush and mountain ranges.

Many moves later following Richard’s academic career, I realized that my childhood self had it wrong: it wasn’t so much the state I love as the aromatic shrub and the region it defines.

Scientists name the plant Seriphidium tridentatum, but most folks call it big sagebrush. Whatever the moniker, this gray-green shrub with the small, silver-hairy, three tipped leaves (hence tridentatum, or “three-toothed”) is the most common shrub in the inter-mountain West.

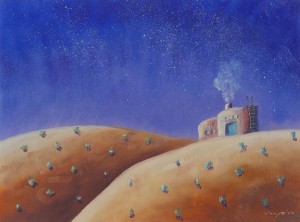

Its evergreen foliage tints miles and miles of open country between the Rocky Mountains and the coast ranges, from Canada south to northern Arizona. When rain or spring snow drenches these expanses of shrub desert, big sagebrush looses its signature fragrance on the air. One whiff, and I know I am home.

At nine, I didn’t know why I loved sagebrush, just that it identified the place where I belonged. After I studied the plant as a scientist, I understood that big sage is so tightly woven into the wind-blown, arid, cold-winter landscapes where it grows that each defines the other.

From its tiny, three-tipped leaves covered with an insulating and water-retaining felt of silver hairs to its varying height and shape, and its behavior of actively reorienting its leaves in response to the movements of sun and wind, big sagebrush is supremely adapted to its environment.

Even its signature scent, the turpentine-like smell, weaves itself into the community as an aromatic advertisement announcing to grazing critters that the ubiquitous plant’s tissues taste bad and are gut-cloggingly difficult to adjust.

It is as necessary to those arid spaces are they are to it. Big sagebrush’s canopy of evenly spaced shrubs shades the ground like a dwarf forest overstory, protecting the cold-desert ground from both searing daytime temperatures and frigid nights. It cuts the constant wind, traps fertilizing detritus, captures rain, and even collects its own mini-reservoir of snow to melt and moisten the ground in spring.

When my homesickness became acute, Richard had just gotten tenure. So I was stunned one evening when he proposed leaving that career behind to move to a place I could call home. Would Salida, his childhood hometown do? He asked. It had sagebrush, I replied.

When Molly arrived home from college that spring, we packed our belongings in the largest rental truck we could find and set out for our new life in a small town a hundred miles from the nearest university (not the mention the nearest city, major airport, or shopping mall.)

Molly found a job at a local coffee shop; Richard took his consulting practice full time, and I worked on finishing my seventh book, the last, it turned out, about somewhere else.

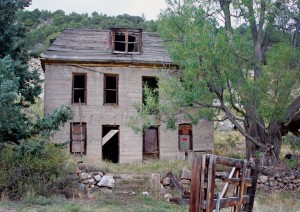

The move did not go exactly as planned: the historic duplex we had bought required more work than we had imagined, from leaking roof and unsafe wiring to original but inoperable windows and spongy floors. And our new space, while charming, had no space for Richard’s shop-full of wood- and stone-working tools.

A few months later though, I found the perfect shop for him, a sprawling and neglected brick building just across the alley. Acquiring it only required buying half a block of decaying industrial property choked in weeds and unwanted debris.

Six years later, we moved our stuff and our Great Dane across the alley into the new house we had built adjacent to Richard’s shop. The house wasn’t finished (who needs trim and doors?) but the consulting work was gone for good and with it, the income we had relied on for building.

But I had finally written myself into home. Belonging came from the native prairie Richard and I lovingly restored in the yard of our formerly blighted site, from the abundance of the organic kitchen garden which yielded food enough to share, and from the connections to the wider community, human, domestic and wild, that we nurtured.

Belonging eventually allowed Richard to pursue the work of his heart: abstract sculpture using native stone as “ambassadors” of the landscapes around us. His basins and sculptures touched hearts and inspired and informed my writing.

What I have learned from writing myself into this place, from the life of a shrub called big sagebrush is that belonging does not arise from a planned, logical sequence of steps. No amount of learning alone can make a place home.

It takes living, rooting as deeply as sagebrush, sprouting branches and leaves that cast shade and invite a community to form. It involves taking the place in, grain by grain and cell by cell, eating from its soil, inhaling its air, nurturing the lives in your own neighborhood, making the place a part of your daily life and your daily life a part of the place.

Belonging means aspiring to contribute to this place I call home in ways as integral as big sagebrush, the plant of my heart, does to the whole region it defines.

And so I sit down to write at a desk full of stories built by my sculptor husband to fit into the bay of windows of my small office. A sprig of sagebrush snipped from the shrubs dotting our reclaimed yard sits on the shelf next to me. I think of the myriad stories woven together to shape this desk, this landscape, and this thing we call life. And then, at home, I put fingers to keyboard and write.

(Adapted from “Writing My Way Home” in An Elevated View: Colorado Writers on Writing, edited by W.C. Jameson)

Award-winning writer Susan J. Tweit is the author of WALKING NATURE HOME, A LIFE’S JOURNEY, and 11 other books, and can be contacted through her web site, susanjtweit.com or her blog, susanjtweit.typepad.com/walkingnaturehome