UPDATED Editors note: John passed away Dec. 8 after sustaining multiple injuries in a car accident on Nov. 12. Please give here if you are able. Thank you.

COOPER THE WHOOPER, a pile of welded and painted farm tools and spare parts, stands on U.S. 160 in the center of Monte Vista. Cooper was my first sighting of John Patterson’s “Farm Art.” Not everyone knows that, once upon a time, Monte Vista National Wildlife Refuge hoped to be a location for the recovery of the endangered whooping crane. The first ever Monte Vista Crane Festival in 1984 was held to celebrate THOSE cranes, not the Sandhill Cranes people flock to see each spring. As nature would have it, the comparatively small and vulnerable Whooping Cranes didn’t make it in the San Luis Valley. All that remains of that dream is John Patterson’s sculpture.

“That was really my start. I’d probably been making art for five or six years for friends and family, Christmas presents and stuff. Then I had a chance with the city [Monte Vista]. They wanted to do something big with a crane and thought something out of steel would be good. They wanted it to be about 7 feet tall. I had just made little things. I wondered if my old welder would build something that heavy, but it did. I traded the crane for two years at the golf course. It worked for the city; they got a free crane. It worked for me; I got a couple years at the golf course. It really started me thinking maybe I could sell some of this stuff, sort of a working hobby. That’s what it’s been. I found my niche as a festival artist. I enjoy festival art because I like meeting people.”

I ran into John at the San Luis Valley Potato Festival last September, where he’d set up an exhibit with some of his work. I was struck again by the humor in these welded piles of nuts, bolts, wrenches, gears and faucet handles. I told him I’d seen one of the four bike racks he’d recently built for the City of Monte Vista, a project organized by the citizens’ action network, Optimystics. The bike racks are public art as much as they are places to hang bikes.

John nodded, “I wish they’d let me paint them.”

I got that. Much of the whimsy in John’s work is in the way he paints it. Two small pieces of steel welded bluebirds onto a perch might look like junk until they’re painted to reveal what John would call their inner spirit.

John calls his work “farm art” because the raw material — other than John’s imagination — is old tools and odds and ends from archaic farm equipment. A fourth-generation farmer in the San Luis Valley, John knows the original functions of the “junk” he welds together. “The old people who’ve been around will start looking at my art and recognize the parts. The parts start telling them a story.”

“With my process, I might start out building a tractor. And the next thing you know, I’m building a flower because the parts said, ‘I won’t go on the tractor, but I’d make a nice flower petal.’ My art is a game I enjoy playing.

“People ask all the time, ‘How do you come up with these ideas?’ I tell them, ‘I play Tinker Toys, and if it looks good I weld it. If it doesn’t, I don’t.’ To me it’s a creative process coming out of the air or out of the spirit of the thing. It usually tells me what it wants to be. Like this.” John points at a beautiful tractor sitting on the table beside us. “I’ve had this clamp for a long time, and I’m like ‘What am I going to do with this clamp?’ And then one day I looked at it and thought, ‘That might be a tractor.’ So I welded it as a tractor.

“These sculptures represent the blood, sweat and hard work of our pioneering forefathers, planting, cultivating and harvesting the bounty of the land. Most people will only see the figures the scrap becomes: dragons, tractors, birds.”

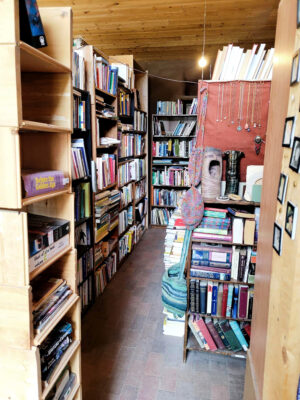

John gave me a tour of his workshop, a workshop filled with time and history.

“The junk I weld is in the corners. Shelves and shelves of it. This is just the inside stuff. I got a whole back full of junk.”

The shelf was overflowing with whimsical beings of the future.

Then John gestured toward a wall of neatly organized shelves filled with old tools and parts. “This is the stuff I won’t weld up. A lot of it I either collected or it was in our old barn when I cleaned it out. I just could not get rid of it. It all has a story, a spirit.” The shelves held planers, old farm tools, ice tongs, clamps — mysterious old things. From the ceiling hung a branding iron, snow spikes and a tool for capturing an intractable hog — a hog wrench. “I’m not sure how it works, but you use it on the snout of the hog. And I think People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals probably stopped them from using those before PETA was even a thing.”

“Even as I’m building my sculptures, I’m thinking, ‘I wonder what the story is on this piece.’ You can tell when a farmer had to really work on something. You can see hammer marks, saw marks, or a cutting torch. You just don’t know the story. I appreciate the parts for what they are.”

John puts his farm art together with something many people might consider a museum piece. “I weld with this old 1949 Forney Stick Welder, still going after all these years. When I post pictures of it on a welding site, a lot of people just laugh at me. But that’s what I am. An old stick welder.”

John handed me a notebook filled with photos of some of his work. “I don’t think you’ve seen these,” he said. I opened the book, turned a page and started laughing. “What are you looking at?” I showed him and he said, “Ah, Fuel Boy!”

“Fuel Boy” evoked every kid I ever saw in the pre-self-service-gas days who rushed out of the station to say, “Fill ‘er up? Regular or high-test? Check your oil?”

“I love steampunk,” John said as I turned the page. “It’s a very interesting genre. It grew up in Europe. It’s people who like to imagine what life would be like if we went back to steam power, the original power that started industry. I like to make these guns.”

John pointed toward the ceiling where a silver and green retro-futuristic “gun” was hanging. “It’s an old JC Penny drill with those graduated silver things from a cream separator. That green bubble on the end is an old hummingbird feeder.”

“And this is my steampunk musical machine. I made it to show kids how much fun it is to use your imagination.”

John, who’s a father and grandfather, appreciates the way children see his art.

“If I do a show and a kid is walking by, I’ll go, ‘You want to learn to twist up a tree or something?’ They will. They’re so into it. I like to open their eyes to the fact that they can do something creative. Maybe that will open up windows to a different thing for them. I’ll give away art for free to a kid who really likes it, hoping to inspire them. I’m not here to make a million dollars.

“At festivals, sometimes parents say, ‘Don’t touch the art! Don’t touch the art!’ And I say, ‘This is the kind of art kids can touch.’”

“I’m a creator, a builder, and it took me a long time to say, ‘OK, no, I’m an artist.’ When you’re having to rely on other people to tell you if your work is good or bad, that’s hard. I think a lot of artists put themselves there, and they shouldn’t because, really, art is for you. When I see good art, I always tell the artist. I think the art community is a good community to be in because we try to lift each other up. I know there are some who try to butt heads, but I’m not that guy at all.”

John is definitely not that guy.

If you would like to learn more about John’s work or are interested in commissioning some farm art, you can reach John at

ArtPostle@gmail.com.

Martha Kennedy, a Colorado native, retired from a long career teaching writing at the university level and returned to Colorado. She lives in the San Luis Valley which she calls Heaven.

[…] article came out today on the Colorado Central Magazine website, so I thought I would share it since many of you asked. The website is having some […]

Nice window into a nice man.

GREAT! Writing, Martha Kennedy. John’s work and John rock!