by Martha Quillen

A friend and I spent a Wednesday in mid-September hiking near Tincup. It was an Edgar Allen Poe sort of day – gloomy, gray and melancholy: “Ah, distinctly I remember, it was in the bleak December.” Except, of course, it was September. On that rainy, cold September day, the brush was wet and the trails muddy. Clouds obscured the ridges, and mist shrouded the evergreens, but golden aspen brightened the slopes.

Although we walked for hours, we didn’t pass a single other person afoot, which was understandable. It was perfect weather for settling into a cozy armchair in front of a crackling fire to read a gothic novel. But it was far too beautiful to stay indoors.

After walking around Mirror Lake, we visited the Tincup Cemetery. I hadn’t been there in a decade or so, and it had changed. I remembered it as an old-fashioned cemetery with lots of fenced-in burial sites, wooden markers, and old monuments, but most of those were gone. There were lots of modern tombstones, though.

In such an historic cemetery, I expected to see numerous monuments to children, but those were rare (having, doubtlessly succumbed to wind and weather). The new occupants were more likely to be in their forties or fifties. And a disturbing proportion of the graveyard’s more recent arrivals had been born after I was: 1951, ‘53, ‘54, ‘55, ‘58, ‘59 ….

At that point it occurred to me that my husband’s fate was, perhaps, not as rare as I had assumed. Even though the average life expectancy in the United States is 78.49, not everyone lives that long. In fact, in late 2010 the national news media reported that life expectancy in the United States had declined. People attributed that development to bad diet, inadequate exercise, laziness, lethargy, smoking, pollution, toxins, environmental degradation, and a rise in obesity and type 2 diabetes.

But what if the primary cause of our lackluster health statistics isn’t our personal failings? What if the U.S. is ranked as the 37th best health care system in the world – behind Costa Rica, Greece, Cyprus, and Colombia – because our care is exorbitantly expensive and therefore many Americans skimp on it?

This June The Atlantic reported that “26 percent of Americans have faced grave financial difficulties due to medical costs, and 58 percent have delayed treatments due to their inability to pay out-of-pocket expenses or co-pays. For those without health insurance or Medicare coverage, a startling 81 percent say they forego treatments, as do 72 percent of poor Americans earning less than $40,000 per year.”

The magazine’s list of health care woes continued.

As did ours. For years, Ed and I held onto an over-priced health insurance policy with ever-rising deductibles. But by the time our girls left home, our premiums were so high, that we avoided regular medical and dental care in order to pay them. So we gave it up. Periodically, we’d consult our favorite insurance agent to inquire about other policies, but prices kept rising. Thus, we started setting aside several hundred dollars a month to cover medical bills. Then Ed was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes, which dashed any hope of him ever obtaining affordable private coverage.

Ed got care (sometimes even exceptional care), but he was always cognizant of the costs – as were his providers. A few years ago, I started worrying about whether Ed’s treatment was going well, because he was too thin, too tired, and too cold. He seemed less enthused about walks, hikes, and outings – and far more irritable than usual. So I urged him to read more about his condition and ask his health care providers more questions. But rather than encouraging Ed to reassess his treatment, that merely convinced him that I didn’t approve of it. So I tried to lighten up.

In retrospect, that may not have been my wisest move. But at the time I didn’t realize how serious his condition was – nor how thoroughly monetary concerns were influencing his decisions. Later Ed got a sore on his foot that required aggressive treatment due to his diabetes, and I started worrying again. I couldn’t help it; I just couldn’t understand why he seemed to be getting worse when his sugar levels, blood pressure, and weight were all reportedly normal and under control.

Finally, after his foot healed, I suggested that it might help to find an expert on diabetes or circulatory problems for a second opinion. Whereupon Ed protested. “But that could cost thousands.”

I concurred, but we had already spent thousands, and I thought it would be worth thousands more if there was a chance we could determine what was going wrong and fix it. Ed protested that even if he needed follow-up treatment we couldn’t afford it.

So I told him if that happened, we could almost certainly qualify for some sort of financial aid. A few days later, Ed died of a heart attack, but after his funeral I found a copy of an email he had written to his health care provider which said that his wife didn’t think he was doing well and he agreed; it also asked what sort of follow-up she would recommend.

It was too late, of course. But that, I suspect, is all too common. Proud Americans try to be frugal and “responsible” and not consume care that they can’t afford. In essence they act just like Ron Paul and his ilk insist they should – which explains why the world’s wealthiest nation has the 37th best health care system.

Clearly, Ed may have died even if he’d lived in Scandinavia or France and had beaucoup bucks; that isn’t in contention. What’s in contention is whether America’s health care system is adequate or just. And the obvious answer is no; our stats suck and people are dying. Yet when Democrats clamor for a medical system that rivals the best in Europe, Republicans cry socialism.

And such systems are socialistic, as are Medicare, and Medicaid; and medical subsidies for children, Veterans, public school teachers, other government workers, Native Americans, and the disabled. And likewise our hospitals, ambulance services, medical research, and the CDC, NIH, FDA, and Colorado Department of Health also rely on tax dollars.

Yet I don’t see many Republicans shunning their Medicare or Social Security checks. Because despite all of the rhetoric, this isn’t really about socialism or freedom. It’s about whether our system will treat everyone, or merely those people that Congress regards as worthy.

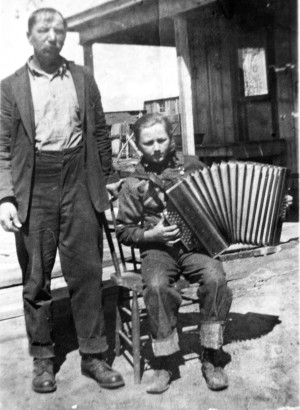

I miss Ed everyday, and so do many other people. He was not just my husband: he was a friend, colleague, father, writer, history buff, and trivia expert. Ed introduced me to journalism, and shared his home state with me, which made me love not just him, but also Colorado, and its past, present and geography.

I love this region and my country, but I am thoroughly sick of the American politicians who question my morals and values while they fight to preserve a health care system that serves insurance companies better than it does patients.

I want to make this clear: I paid Ed’s ambulance, hospital, and mortuary bills (with some generous help from my friends and family). And while Ed was alive, he paid for all of that Social Security, Medicare, and disability insurance that he will never use.

Ahhhh, but maybe that is the Republican plan: They can reduce costs by supporting policies that dispatch patients to early graves. And yes, that sounds a bit extreme, but what other reason could they have for praising a dangerously inadequate health care delivery system that’s costlier than any other in the world?

As of late September, Martha Quillen was alive and apparently well in Salida.