by Virginia McConnell Simmons

Ute Indians say they were always here, but, like migrations of other emigrants, theirs began far away. It started in Central America and Mexico thousands of years ago and ended on reservations in Utah and Colorado.

The Ute and other Uto-Aztecan people, whose language is reflected in Utah’s state name, moved north to southeastern California and the Great Basin of Nevada and Utah, anthropologists believe, sharing the numic linguistic family that included other tribes such as Hopi, Paiute and Shoshone. From there, the nomadic Ute people gradually moved north and east through Utah and the mountains of Colorado and New Mexico by about 800 years ago.

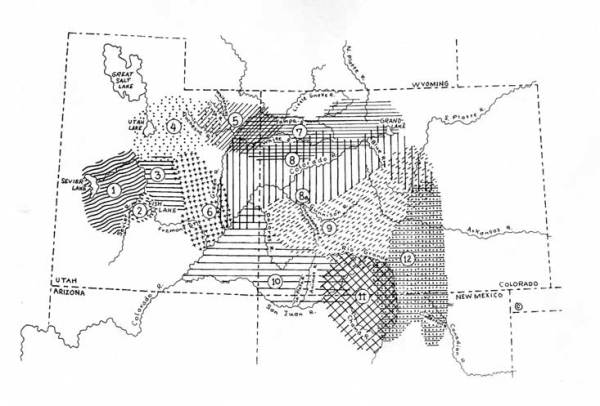

They became several bands; perhaps the band best known by today’s residents of central Colorado is the Tabeguache band. The Muache band was in the region along the Front Range of southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, the Wet Mountain Valley, and part of the San Luis Valley. The Capote band, farther west in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, also came into the San Luis Valley from time to time, while the Weminuche (Weenuche) band of southwestern Colorado visited it infrequently.

Dependent on natural resources, members of the various Ute bands roamed in extended or small family groups, hunting and gathering natural resources to secure food, clothing, tools, weapons and shelter, with some variations in lifestyles in different locales, especially around Utah’s lakes and marshes. Tabeguaches enjoyed a splendid area that included the Upper Arkansas River Valley; South Park; headwaters of the Rio Grande, Gunnison and Uncompahgre Rivers; and Elk, Sawatch, Mosquito, San Juan and part of Sangre de Cristo Mountains.

Ute country was bounded by other tribes; hostilities often resulted when they met during hunting expeditions. In the Four Corners area were Navajo; Comanche were in southern Wyoming; Kiowa moved down the plains around the beginning of the eighteenth century; Arapaho and Cheyenne came to Colorado about 1800; Apache or Navajo-Apache dominated to the south; and Pueblo villages were plundered for food, livestock, goods and captives. Occasionally hostile nomadic tribes entered Ute territory, as happened with a legendary battle between Utes and Kiowas east of Antonito in the San Luis Valley and with Arapahoes in South Park near Garo.

After the arrival of Spanish explorers and colonizers, horses became part of the Utes’ lifestyle, allowing farther and faster travel, and they even hunted occasionally as far east as Kansas and Oklahoma. The first known conflict with Utes took place in about 1600, when mounted Spaniards came north in a wildly unsuccessful attempt to corral bison for domestication. When they met Utes on foot with a supply of meat and corn, probably stolen from Taos Pueblo’s fields, a clash ensued. By the 1630s, some Utes were taken to Santa Fe for forced labor, but a few escaped with horses, abetting the tribe’s transition as horsemen, while women or dogs with travois also continued to carry burdens.

By the mid-1700s, intermingling was also occurring in outposts like the Chama Valley, where Christianized Indians (genízaros) of various tribes were being relocated for labor and defense. Profitable trade at fairs like Taos’s also enticed Utes to bring their captives to trade. Usually peaceful, encounters took place with Utes and Spanish expeditions – notably those of Rivera, Domínguez-Escalante and Anza, while relations with French-Canadian and American trappers and traders could be good or somewhat bothersome, and those with American explorers went well (an exception being the fate of Gunnison in Utah). Meanwhile, the earliest attempts by Hispanic herders and farmers to settle as far north as the San Luis Valley failed due to raids.

Transformation came in the second half of the 1800s after the Mexican-American War and the acquisition of the Southwest by the United States. Now in rapid succession came the American military forts; territorial government; Indian agencies; settlement on land grants; settlement in Utah; fifty-niners and mining camps with populations as large the entire tribes; destruction of game and other natural resources on which the Utes depended; towns, farms and ranches. A treaty in 1868 was supposed to keep all Ute Indians at a distance, west of the Continental Divide; but wandering continued, and discovery of riches in the San Juan Mountains led to new problems.

Under Chief Ouray, Tabeguaches made concessions on their land west of the Divide with the Brunot Treaty (Agreement), while three other Ute bands were restricted to the Southern Ute Reservation in a strip along the southwest border. Its administration, with headquarters at Ignacio, Colorado, served Muaches, Capotes, Weminuches and, briefly, Jicarilla Apaches. The Meeker Massacre at the White River Agency in northwestern Colorado in 1879, however, brought disaster for the Tabeguaches who, for no reason except to get them off prime real estate, were then removed to the Uintah and Ouray Reservation in Utah, with headquarters at Fort Duchesne. With them were all Utes of northern Colorado and Utah. Within a few short years at the Southern Ute Reservation, led by Chief Ignacio, Weminuches elected to split from the others and received the western end of the reservation, henceforth to be called the Ute Mountain Ute Reservation with headquarters at Towaoc, Colorado.

Thus, the vast region once occupied by nomadic Ute Indians in western North America was whittled down to three reservations, where the United States Government expected them to become sedentary farmers. The Ute Indians had stood in the way of “progress” too long.

Virginia McConnell Simmons is the author of The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico and of other histories of this region and the West. The map of Ute Indian bands accompanying this article is from her book, with permission of its publisher, University Press of Colorado (©2000).