by Hal Walter

The old rancher told me

This time of year

it’ll blow and blow and blow

until it snows.

He’s gone now

but I remember him

in March, April and May

When the wind howls

for days on end

The trails I run turn to sand,

the fine dirt has flown

Grasshoppers scatter with each step

and my eyes are full of grit

Then one day it’s still

and the big flakes fall

I keep my eyes on the trail

because I cannot see ahead through the falling snow

Somewhere off in the white

a meadowlark sings

His voice hangs on the stillness

of each falling flake

Last fall as I awaited the arrival of winter with all the enthusiasm of a condemned man looking over a menu for his last supper, I marveled at day after day of golden fallish weather. “Every day like this is one day less of winter,” I told myself in hopes of warding off the feeling of gloom that sets in when the days grow short.

And now, as winter fades to spring and the days grow longer in the run-up to the Spring Equinox, I often find myself saying “Every day like this is another day closer to summer.” True, winter came late to Central Colorado this season and seems to be leaving early, too. It also gave us some nice breaks, including some spectacularly beautiful days in February.

But I do seem to recall a few truly Arctic moments from early December to mid-January, and some actual brutally cold days, though our nighttime lows were nowhere near the sub-zero stuff we saw the last two winters. And it must have snowed sometime, otherwise the overall Arkansas River Basin would not be registering over 100 percent of average snowpack on the Ides of March.

Still, the milder winter has some local residents freaking out about moisture, the possibility of a drought and the fear of wildfires. Of course it could happen, but I bet not. An old rancher once told me, “This time of year it will blow and blow and blow until it snows.”

I can think of only one year in a quarter century that he was wrong.

I’ve lived in the Wet Mountains for 25 winters, and from my experience this past winter was fairly typical. The idea of winter snowpack, such as it is, at moderate altitudes under 10,000 feet is vastly overrated, and in very few years has January-February snowfall at these altitudes provided significant amounts of moisture. Moreover, it’s been the wet spring storms in late March, April and even May that make the green grass grow in June.

Frankly, the high-country snowpack above 10,000 feet is largely the concern of Front Strangers who depend on this snowmelt for municipal water supplies, though it also figures into our region’s agriculture. The fretting over snowpack is partly a machination of the Front Range mainstream media, which reports on the subject as if it can sway public opinion to affect the weather.

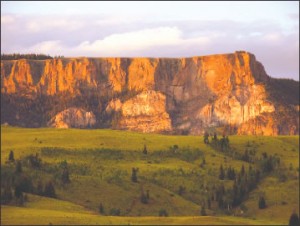

One only needs to look at the vegetation to gain an understanding of how snow and summer moisture work at moderate altitudes and in the snow shadows of our larger mountain ranges. The north-facing slopes hold the trees that require more water — spruce, fir, aspen and Ponderosa pines. That’s because these slopes are shaded from the low sun most of the winter and can harbor snow.

The south-facing slopes, on the other hand, are where you find pinion pine, juniper, scrub oak and yes, even yucca and cactus. In these areas you can find some of these desert plants even at altitudes of 9,000 feet or higher.

These vegetation microclimates are particularly evident in the shadows of the larger ranges such as the Collegiate Peaks and Sangre de Cristo mountains.

There’s usually not that much water content in the snow that falls in the coldest months, and often the process of sublimation literally sucks the moisture out of what snow we do get. Moreover, the ground is frozen, and the snow insulates the ground from the sun, so when it melts it runs off and often does not soak in.

It’s quite different when a heavy wet snow falls on the bare ground in late March or April. In 2003 we had very little snow all winter but a storm dropped a whopping seven feet of snow starting March 17. I think we’re still drinking water from that storm. Likewise, we had more than two feet in late April 2004.

Now when it comes to snowpack in the high country it’s a different story. This snowpack at higher elevations does add up, and when it melts in late spring the water feeds the streams and ditches that irrigate hayfields and other crops. Evaporation from this moisture also helps fuel summer thunderstorms.

When it comes to high snowpack, we’re actually still ahead of the game, though this lead has been eroding in recent weeks. The South Colony SNOTEL in the Sangre de Cristo range registered just over 100 percent of average in mid-March. The water content rested at 86 percent of the average peak, which occurs on April 15. That leaves about a month to make up 14 percent. One or two good spring storms could push the snowpack over that average.

And one of those spring storms could certainly arrive after April 15. I’ve seen a number of late spring snowstorms, including one whopper in late May. So anything is possible.

For several days now I’ve been waiting for a cow I call “Number 30” to calve. She’s been showing all the signs, beginning with a swelling udder. This morning with a fresh coating of snow on the ground and a gray fog hanging low over the Wet Mountains, I checked on her and the other cattle. They just looked at me and munched hay. The calf, like the snow, will arrive when it arrives.

As I walked back to the truck I heard a sound that was completely out of context and looked up to see a pair of Canada geese honking and flapping against the gray sky. There’s no large body of water within miles and the sight of flying geese is quite rare here at 8,800 feet in the Wet Mountains.

I watched as the geese zigged and zagged across the sky, heading generally north. They dropped behind a ridgeline and disappeared in the clouds. But I could hear the honking in the dead-still air for some time after they had dropped from sight.

In a couple of days the wind would blow again, and when it stopped it would snow again. I just knew it.

Hal Walter writes and edits from the Wet Mountains. You can keep up with him regularly at his blog: www.hardscrabbletimes.wordpress.com