Article by Allen Best

Recreation – September 2005 – Colorado Central Magazine

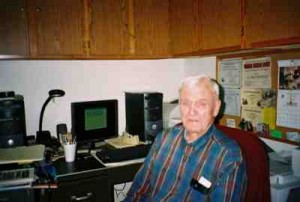

MAURY REIBER can claim a distinction like no other in Colorado. He owns the highest of Colorado’s privately owned high-end real estate, the summit of Mt. Lincoln. At 14,291 feet, it’s Colorado eighth-highest mountain.

But even if very few people own a mountain summit, Mr. Reiber remains in rarified company in another way. He is Colorado as it used to be – a person who values Colorado real estate as much for what can be grubbed from it as for its scenery. He is, at heart, a miner.

That rarity shoved him into the newspapers this summer after it was reported – incorrectly, as it turned out – that the Forest Service had ceased issuing permits to climb Mt. Lincoln and others of the fourteeners in the Mosquito Range. In fact, the Forest Service never issued permits. How could it? It does not own the land. It does not even issue permits for any mountains in Colorado.

But the newspaper did get the story right that Mr. Reiber and other mine owners are worried about their liability while they wait for metal prices to rise. That fancy led Mr. Reiber to buy the 9.46-acre parcel atop Mt. Lincoln and, individually or in partnership with others, some 233 acres on the mountain as well as hundreds of other mining claims in the Mosquito Range between Fairplay and Leadville. They believe the price of silver and other precious minerals will someday rise again to the level necessary to make these mines valuable. “One day – it may not be in my lifetime, but hopefully in that of my heirs,” says Mr. Reiber, who is 75.

If Mr. Reiber is an anomaly among Coloradans, so is the Mosquito Range anomalous among Colorado landscapes. In recent years, vast chunks of old mining properties in the backcountry have been purchased by land-preservation groups such as the Wilderness Land Trust and the Trust for Public Land. They, in turn, sell the properties to the Forest Service and other federal land agencies as federal funds become available.

The goal is to avoid development of the parcels, whether by mining or, more commonly, for backcountry cabins. The mountains around Breckenridge and Fairplay in particular are dotted almost to timberline with homes and some weekend and vacation cabins. Near Aspen, as land prices escalate on the valley floor, the well-heeled are increasingly studying remote, mining parcels – much to the concern of local governments charged with dispatching fire trucks and otherwise providing public services.

“I can show you example after example of mining claims that are being developed as second-home sites,” says Doug Robotham, the Colorado director of the Trust for Public Land. “It’s not a theoretical thing. And it goes right up to timberline.”

In places, the transfer of private lands into the public realm has been sweeping. In the triangle of Silverton, Ouray, and Telluride, for example, a consortium of governments and non-profit groups has transferred 8,000 acres of old mining properties into the federal administration during the last several years. A similar effort is now underway in the mine-pocked Elk Range between Aspen and Crested Butte.

But the story in the Mosquito Range is different in several important respects. First, unlike Aspen, Breckenridge and a number of other old mining towns, a skiing-based tourism and real estate economy did not rush in to fill the void in South Park. Instead, people like Mr. Reiber, who expect the mines to someday reopen, remain influential in county politics. Second, private lands among the high peaks are more extensive. The ore deposits in the blue limestone generally swept up well above timberline, which is why Lincoln – but also its companion fourteeners of Bross, Democrat, and Sherman – came into private ownership.

Mr. Reiber is as much mining historian as he is mining speculator. His mine atop Mt. Lincoln, called the Present Help, was staked in 1871 – five years before Colorado was even a state, he feels compelled to stress. It was patented, or put into private ownership, in 1882. The plot, like others authorized by the Mining Act of 1872, is 300 feet by 1,500 feet long.

NEAR THE PRESENT HELP is another mine, called the Russia, which has a tunnel that bores 968 feet into Mt. Lincoln at an elevation of 13,990 feet. The Russia converges with the Present Help in the interior of Lincoln at an elevation of more than 14,000 feet. It is believed to be the highest mine in North America and, the extreme elevation notwithstanding, it was worked year-round in the 1870s and 1880s. It made men rich, if not necessarily millionaires.

Silver was the principal metal in most of these mines. As such, their best days were prior to 1893, when the federal subsidy for silver was withdrawn. Still, the ores are so good that the mines have since been worked sporadically, most extensively during the 1920s.

Mr. Reiber’s involvement in mining began in the 1940s, soon after he moved with his family from Nebraska. An uncle gave him his first experience with mining, and he remembers disliking it. His task was to muck, or shovel, ore. He didn’t get the mining bug until the 1950s. He remembers seeing a television program in which the speaker explained that making money in most cases required having money to invest. But not mining, said the announcer. Only in finding deposits of silver, nickel, and uranium could a poor man become rich.

That’s what Mr. Reiber has been trying to do ever since. While working first in sheet metal, heating and air conditioning and then as a building inspector in Denver, Mr. Reiber steadily bought more mining properties – something he continues to do under the business title of the Earth Energy Resources Co. In many cases during the 1960s and 1970s and even the 1980s, such properties could be had for back taxes or even less. Working on weekends and vacations, he extracted silver ore from several mines and dumps. They trucked that ore first to Leadville and, later on, to a reduction mill in Denver, from which it was shipped to a smelter in El Paso, Texas. Mr. Reiber says whatever profits he made from the ore were eaten up by shipping – not the first miner to come to that conclusion.

STILL, HIS MINES do have ore. When prices spike, mining companies get interested. This has happened twice to the mines on Mt. Lincoln, first in the 1960s and then again in the mid-1980s when the attempt by the Hunt brothers in Texas to control the global market for silver sent miners scurrying to their veins. At one point, a giant air compressor was placed atop Mt. Lincoln. Wryly, Mr. Reiber notes that it takes a lot of work to compress air at 14,000 feet. Air density there is 65 percent of what is at sea level (it is 79 percent at 8,000 feet, or the elevation of Buena Vista).

When Mr. Reiber first started his weekend mining hobby, he was mostly alone among the rocks. “Back in the 1950s and ’60s, a lot of days you wouldn’t see anybody at all. On weekends you might see two or three people on the pinnacle (of Mt. Lincoln) – if the weather was good.”

That began changing in the 1970s. There was no trouble at first, but he distinctly remembers the day when a particular hiker happened by. “You’ve got one hell of a liability issue here,” the hiker, who identified himself as a lawyer, told him. He didn’t mean it as a threat, only as an observation.

In the years since, the number of hikers and four-wheel-drivers and motorcyclists has ballooned. Much of the hiking profusion can be traced to 1978, when Walter Borneman and Lyndon Lampert published A Climbing Guide to the Colorado Fourteeners, the first in what is now a shelf of such guide books. With many climbers striving for what is called a grand slam, reaching the top of all 54 of the peaks above 14,000 feet, the numbers swelled during the 1980s and 1990s. The continued increase is now estimated at 10 percent annually.

MR. REIBER HAS NO specific bone to pick with hikers. By all accounts, he is a genial individual, polite and friendly. But in recent years he has become increasingly concerned about his liability if, for example, someone fell into one of his shafts. While no such lawsuit seems to have ever been filed, he and other mine owners insist a careful inspection of the law leaves no doubt.

That law, the Colorado Recreational Statute, seeks to exempt rural landowners from liability so that farmers, for example, will allow hunters on their property to hunt pheasants. But, says Mr. Reiber, the law exempts “attractive nuisances,” which he believes might apply to mine shafts. Even if somebody is not specifically invited, he says, specific efforts to keep them out can be construed as an invitation. Trying to erect fences across Mt Lincoln, of course, is a task that would challenge even Christo.

As a short-term salve to the mine owners, the Forest Service earlier this year began distributing a notice to fourteener climbers. “All these peaks are PRIVATELY owned,” reads the leaflet, which is handed out at the district ranger’s office in Fairplay. “Trails and roads going to the top of these peaks are NOT under USDA Forest Service jurisdiction.”

NO EFFORTS TO DISCOURAGE HIKERS has been made at Kite Lake and other trailheads, although news of the case has caused some would-be hikers to seek out his permission. He has not given them permission. “You just can’t say yes,” he explains, because to do so would be to invite liability. “It’s so sad.” A miner first, he also understands the lure of the summit. “I do love the view from Mount Lincoln, I think its one of the most awe inspiring in Colorado.”

But while none seem to doubt Mr. Reiber’s concern about liability, his more immediate problem, he says, has been with four-wheelers. They are more likely to drive to his mines, vandalize his locks, tear down his gates, and sometimes make off with his goods – be it rocks for ornamentation or old shacks for their weathered wood. “It wasn’t the hikers,” he says. “It was the people who had the trucks, because they were the people who we felt were really doing the damage.”

There are few, if any, outside models for the Mosquito Range to emulate. Access to Culebra Peak in the Sangre de Cristo Range, the only other fourteener still privately owned, is limited to those willing to pay the $100 the owners demand ($30 on July 4th weekend). However, they also own virtually the entire mountain down to the valley floor near the town of San Luis. Public roads go into the heart of the Mosquito Range.

One idea is for the Forest Service to extend immunity to the private lands. But why? It owns less than half the land in the Mosquito Range. Another idea is for the Forest Service or some other nonprofit to purchase a trail easement. A well-defined trail, reinforced by signs, would discourage people from going to the mine workings. But the Forest Service would want a long-term lease. “We don’t want to put a lot of investment into a trail that might be gone in 12 months,” explains Sara Mayben, district ranger in South Park.

Mr. Reiber is also having none of it. “If I were to give an easement, it would have to be revocable,” he says. He does not want anything to hinder development of the mines come the day of soaring silver prices.

Yet another option is for the mine owners to sell to a non-profit such as the Trust for Public Land, as landowners elsewhere in Colorado have done, with presumed transfer to the Forest Service. Mr. Reiber doesn’t reject this notion, but says it would have to be the right price. “If the numbers were right I’d consider it,” he says. “But it’s not going to be for peanuts, because of what’s underground and what’s in the (mine) dumps.

The Trust for Public Land’s Doug Robotham acknowledges an outright purchase of either all the key lands or rights-of-way remains possible. But work on the Mosquito Range is just beginning, and from long experience, Robotham describes a tedious process. “These negotiations are often very complicated and take time and require patience,” he says.

Yet another idea is for Park County – or for that matter, the Colorado Mountain Club or a four-wheeling group – to cite a federal regulation called RS 2477 to assert use of long-used public roads. That would involve claims against both the Forest Service and the private landowners. But James Gardner, a Park County commissioner regarded as most vigilant of private property rights, will have none of that idea. “Sure, we could declare the RS 2477 right-of-way, but then it really gets adversarial,” says Mr. Gardner. Clearly indicating where his sympathies lie, he suggests darkly that a preservation group might even precipitate injury in order to justify a lawsuit – to push property owners toward sale of their mines. But a judicial ruling is uncertain and, in any event, at least the Colorado Mountain Club has no interest in RS 2477.

SEVERAL OTHER IDEAS have been broached, including amending Colorado law to protect landowners like Mr. Reiber from liability in this and similar cases. Several state legislators are reported to be discussing the idea.

T.J. Rappaport, executive director of the Colorado Fourteeners Initiative, which seeks to minimize erosion and other damage to Colorado’s high peaks from overuse, thinks an answer will soon be found. “I wouldn’t pretend to know what the solution is, but there are enough people who want to climb in these mountains that somebody will come up with a creative solution that I think will prevail.”

The subject is addressed in a document called the Mosquito Range Heritage Initiative, which was issued in June. A group called the Alma Foundation, in partnership with Park County government and the Trust for Public Land, set out to address the increasing land-use conflicts. The report outlines goals of public access but also defines the goal of “heritage tourism.” In other words, it values the old mines for their history – and also implicitly acknowledges the potential they could be worked in the future. On the subject of the access to Lincoln and the other fourteeners – Cameron, Sherman, and Bross – the document also identifies potential contributors being land-preservation groups; hiking and four-wheel-drive clubs; plus local, state, and federal governments.

In the Park County courthouse, Mr. Gardner, who grew up wandering through the Mosquito Range as a boy, welcomes a solution that will allow hikers legal access to Lincoln, Sherman and other high peaks, but sees little loss if none is delivered.

“We probably derive almost nothing from the fourteener climbers,” he says. “I doubt that a lot of them even spend a dime while in Park County. The same thing goes for mountain bikers and backpackers,” he adds. Those that do spend money are more likely to spend it in adjacent Summit County, which has a highly developed tourist infrastructure because of the ski industry. Of tourists, only hunters leave a great deal of money behind.

“Part of this is our own fault,” adds Mr. Gardner. Fairplay and Alma just lack the hotels and other accommodations that might cause the peak-baggers, wildflower pickers and others to linger.

Like Mr. Reiber, Mr. Gardner hopes for a return of active mining. “I am convinced that sooner or later, something will come along to make it profitable again,” he says.

ONLY LIMITED MINING has continued since World War II, with the South London continuing gold production until the early 1980s. In 1995, the Sweet Home Mine resumed production, this time for rhodochrosite crystals, but closed a year ago.

Mr. Gardner says Park County has become the epitome of a bedroom community, mostly for metropolitan Denver, but also to the resort economy of Summit County. Only 20 percent of workers who live in the county work there.

This leads to a startling statistic. Park County, he says, has the lowest amount of commercial property in Colorado per capita. Because, under the Colorado Constitution, residential property is taxed at a lower rate, commercial properties carry the heavier burden for delivering both property taxes and sales taxes. That leaves governments in south Park anemic.

“It’s a difficult situation here,” says Mr. Gardner. “We’re too close (to Summit County) to be far, and too far to be close. We’re the epitome of a bedroom community.”

Although mining companies still maintain interest in the Mosquito Range, the money trails suggests a different story. Tellingly, the Coors Brewing Co. purchased the water coming from the London Mine for $1 million, to be used for real estate development near Brighton. The mine itself has yielded no gold recently.

Mr. Reiber offers similar testimony. By his own admission, his mining has produced more expense than income. “Sometimes I think I’m nuts, but everybody has to do something,” he says, adding, “At least it kept me out of the bars.”

Allen Best has climbed many of Colorado’s 14ers, and some of those excursions required trespassing in the Mosquito Range.