By Jan MacKell Collins

By Jan MacKell Collins

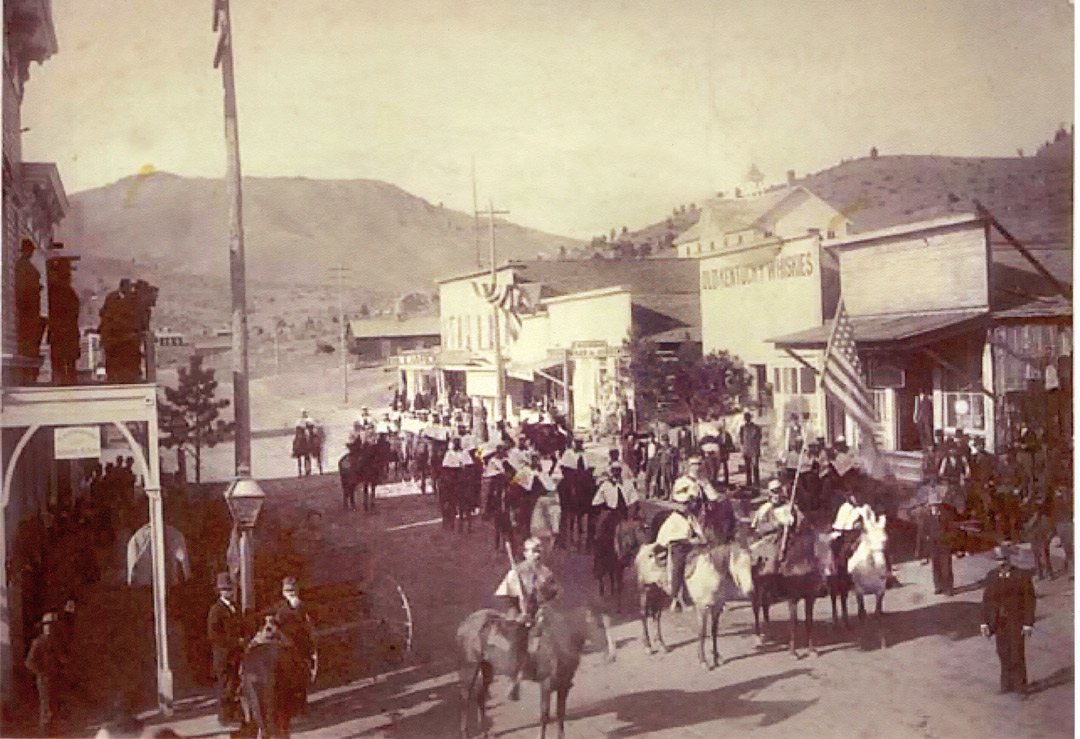

Elkton – Boom and Bust

Named for the nearby Elkton Mine in 1894, this town in the world-famous Cripple Creek District once had a population of 2,500 people. All three railroads of the District once served Elkton, and a special siding was constructed for the sole purpose of transporting gold ore from the Elkton, the Cresson, and other big mines. In Elkton proper, streets of the community were laid out in tidy rows on the hillside, with miner’s cabins and small houses lining up next to one another. There was a school, plus several restaurants and shops, and a post office which opened in 1895. Being a family town, Elkton had only one saloon.

Elkton eventually absorbed the smaller towns of Arequa and Eclipse, and served several area mining camps whose residents received their mail there. By 1916, the Elkton Mine had produced $16.2 million in gold, but mining was becoming too expensive and production throughout the District was slowing dramatically. Only 350 people remained by 1919, and the post office closed in 1926. Up to the 1950s, however, a few people continued calling Elkton home.

Elkton eventually absorbed the smaller towns of Arequa and Eclipse, and served several area mining camps whose residents received their mail there. By 1916, the Elkton Mine had produced $16.2 million in gold, but mining was becoming too expensive and production throughout the District was slowing dramatically. Only 350 people remained by 1919, and the post office closed in 1926. Up to the 1950s, however, a few people continued calling Elkton home.

When the last resident left in the 1970s, Elkton officially became a ghost town. Throughout the 1980s, several homes and buildings remained, some still containing furniture and other items from days gone by. In 1994 this historic treasure, and even the mountain upon which it perched, was bulldozed by the CC&V Mine in a frantic search for more gold. Prior to the destruction an archaeological dig was conducted at the town, but any remaining artifacts were sent to an out-of-state university and local museums received nothing. The loss was followed by more destruction in the District; by 2015 all but one of the area ghost towns, which is now on private land, had been destroyed.

Sopris – Town Flooded

Named for General E.B. Sopris, this town outside of Trinidad was built very close to an older settlement called Cariposas. Three other camps, Jerryville, Piedmont and St. Thomas, were located due east. There was also Sopris Plaza. Sopris proper was established by the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company, which owned the Sopris Coal Mine. The post office opened in 1888. In its time, Sopris was amongst the oldest of CF&I’s company towns.

By 1890 there was a bakery and blacksmith at Sopris, and the Colorado Supply Company was the only general store. The mine grew to include over 300 coke ovens. Quaint wooden miner’s houses were soon sprinkled through the town, and one neighborhood was known as “Little Italy.” By 1907 the population was 500. Children were attending Lincoln School, and there were more businesses and stores. Being a company town, however, the Sanborn Fire Insurance map noted most of the buildings were of “cheap construction.” There was never a fire department or water works.

Still, the people of Sopris loved their little town. They say that the population peaked at around 2,400, a number that included the town and outlying communities. By 1910, the number had downsized to around 900. When the coal ran out, the Sopris Mine closed in 1930 but residents continued living there.

In 1955 it was announced, without argument, that a dam would be built across the Purgatoire River, thereby flooding Sopris. It took some time for the project to commence as residents left and bodies from the cemetery were moved. The post office closed in 1969, the dam was finished in 1970, and a final service at St. Thomas Church was held on Christmas Eve in 1971. The buildings were razed and today, Sopris lies at the bottom of Trinidad Lake. Former residents gather every few years at the lake, to remember and honor their town.

[InContentAdTwo]

Rosita – Mob Murder

Gold was discovered in the area around Rosita as early as 1863, but it was not until 1872 that the town was founded. In a short time, Rosita evolved from a farming community to a rollicking silver mining camp. Within two years, primitive tents and cabins had been replaced by more substantial homes, and businesses included a saloon and a hotel. When the post office opened in 1874, over 1,000 people lived there. The next year, Rosita made national news during the Pocahontas Mining War, which resulted in the mob murder of Civil War veteran Major George Graham.

Gold was discovered in the area around Rosita as early as 1863, but it was not until 1872 that the town was founded. In a short time, Rosita evolved from a farming community to a rollicking silver mining camp. Within two years, primitive tents and cabins had been replaced by more substantial homes, and businesses included a saloon and a hotel. When the post office opened in 1874, over 1,000 people lived there. The next year, Rosita made national news during the Pocahontas Mining War, which resulted in the mob murder of Civil War veteran Major George Graham.

By the time Rosita became the Custer County seat in 1878, the population had doubled. One of the biggest breweries in the state, as well as a cheese factory, were well known throughout the region as Rosita became a social center.

When the silver mines ran out in the 1880s, however, Rosita’s population dwindled as residents moved to the still-profitable communities of Querida, Silver Cliff and Westcliffe. A fire in 1881 burned several prominent buildings, which were never reconstructed. In 1886, Silver Cliff was able to snatch the county seat, but Rosita remained resilient for a few more years. Colorado Governor Ralph Carr was born at Rosita in 1893.

When the silver mines ran out in the 1880s, however, Rosita’s population dwindled as residents moved to the still-profitable communities of Querida, Silver Cliff and Westcliffe. A fire in 1881 burned several prominent buildings, which were never reconstructed. In 1886, Silver Cliff was able to snatch the county seat, but Rosita remained resilient for a few more years. Colorado Governor Ralph Carr was born at Rosita in 1893.

In 1958, some of the historic buildings were restored during the filming of “Saddle the Winds.” Rosita’s short claim to fame failed to draw more residents, and the post office closed in 1966. On a visit in 2015, hardly anything in Rosita was recognizable from the old days. The town is now overrun with suburban housing, much of its history gone forever as older buildings have been remodeled, torn down, or lie in ruins. The most historic landmark these days is the beautiful old cemetery.

Dearfield – Dreams Dashed

Historically speaking, much of Colorado’s population in the old days were white, Irish and Catholic. By the early 1900s, prejudices against African Americans remained glaringly evident; most citizens could find only menial jobs. Enter Oliver Tousaint Jackson, who in 1910 established Dearfield as an agricultural center for blacks who met with oppression elsewhere.

“I found it difficult to get the people in the land office to pay very much attention to a negro,” Jackson later recalled. The determined man was able to enlist the help of Colorado Governor John Shafroth to achieve his dream. Within a year eleven families lived at Dearfield. Even the poorest families found a community providing education, farmland and unbiased camaraderie among residents. Together, the residents managed to dry-farm the land, raising vegetables and chickens.

That first tough winter, when fuel and food were scarce, came to be a trademark of Dearfield. Assistance came from the state agricultural college, but dreams of a canning factory, large hotel and other enterprises never materialized. When the market fell after WWI, Jackson turned from farming to just selling lots in hopes that Dearfield would still grow. The peak population, in 1921, was about 700. Many longtime residents were in debt, however, having borrowed during better times but who now had trouble making payments.

Drought and the Great Depression killed the town in the 1930s, and by 1940 only twelve people remained. Historians see now that Dearfield was a worthy but unsuccessful endeavor, especially after Jackson was forced to retire from his project and move on in 1939. More important, however, he deserves better recognition for finding a viable, non-violent way to combat racism in his time. The last resident, Jackson’s daughter, left in 1973.

Ludlow – A Massacre

Ludlow’s post office opened in 1896, but little is known about the town until 1914 when one of the bloodiest battles in labor history occurred near there. At the time, Colorado Fuel & Iron owned several area coal mining camps and towns. Employees in these places were not allowed to shop anywhere but the company store. They could not choose their own doctors, and were forced to live where CF&I told them to live. The men worked long hours at minimal pay, without compensation for side work that did not entail actual mining. Company guards kept everybody in line.

By 1913, the miners had enough. With the help of the United Mine Workers of America, some 10 to 12 thousand miners went on strike. They were immediately ousted from their company homes by CF&I, and relocated to small camps that had been prepared for them by the UMWA. The camp near Ludlow was the largest of these. For fourteen months, dozens of families lived in tents, weathering the winter and struggling to survive.

By 1913, the miners had enough. With the help of the United Mine Workers of America, some 10 to 12 thousand miners went on strike. They were immediately ousted from their company homes by CF&I, and relocated to small camps that had been prepared for them by the UMWA. The camp near Ludlow was the largest of these. For fourteen months, dozens of families lived in tents, weathering the winter and struggling to survive.

Tensions increased, threats were made, and ultimately, CF&I enlisted the help of the National Guard as the strikers refused to budge. On April 20, 1914, guardsmen from both CF&I and the National Guard descended upon the Ludlow camp and opened fire. The dead included at least nineteen miners, but also two women and eleven children who suffocated in a hole beneath the wood floor of a burning tent. The battle spurred further violence before things settled down.

For years, a memorial has marked the site of the battle. In 2003, vandals cut off the heads off a statue depicting a man, woman and child. The statue has since been restored, a reminder of the violent and unnecessary battle during what is now known as the Ludlow Massacre.

Jan MacKell Collins has stumbled her way through Colorado’s ghost towns for over three decades, recording the past so we can preserve them for the future.