by Judy Suchan

Two aggressive railroads, hastily built forts, a cannon commandeered by the legendary ‘Bat’ Masterson, gunfire, and a legal battle that raged in the courts for almost two years. This was the little known Royal Gorge War, an event that helped shape Colorado’s, as well as the nation’s transportation system.

In the late 1870s, miners converged on the Arkansas River Valley of Southern Colorado in the search for silver and lead. Feverish mining in the area led to the town of Leadville and attracted the attention of two railroads, the Denver & Rio Grande (D&RG) and the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe.

Both railways had tracks in the lower Arkansas Valley at the time. The Santa Fe was at Pueblo, about thirty-five miles east of Cañon City where the Denver & Rio Grande had its tracks. Leadville was over one hundred miles northwest of Cañon City.

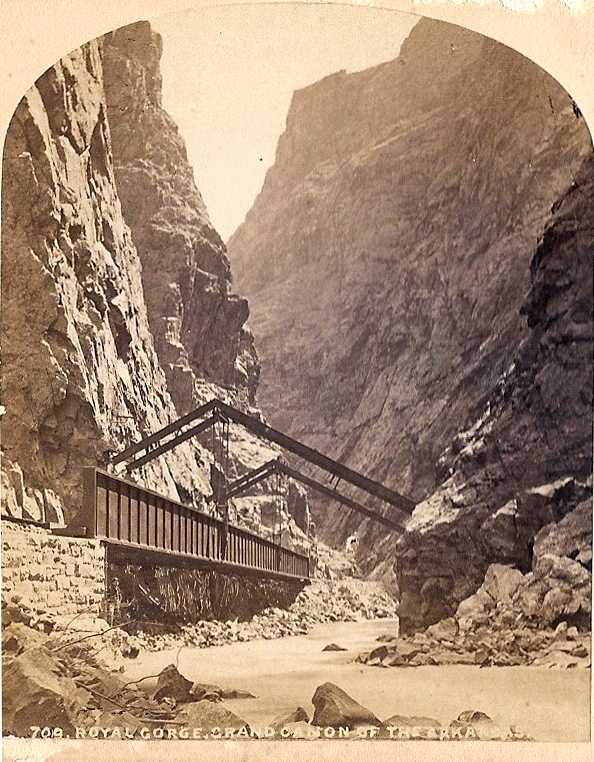

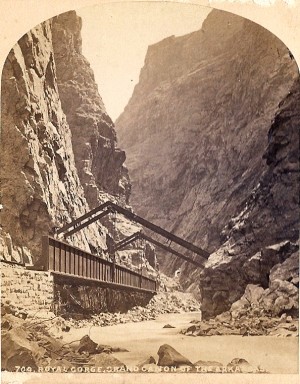

Normally two railroads occupying the same valley would not be a problem, but west of Cañon City, and on a clear path to Leadville, stood the formidable, 10-mile-long, Royal Gorge canyon, a chasm that in some places is 1,250 feet in depth and 30 feet at its narrowest point, with sheer granite walls that plunge into the tumbling Arkansas River, creating an impassible barrier.

Both railroads wanted the right of way through the gorge to the rich mining fields in Leadville. But with room for only one set of tracks, the war for the gorge began between the two rail lines.

In April of 1878, a construction crew assembled by the Santa Fe railway began grading for a rail line west of Cañon City at the mouth of the gorge. The D&RG, which had track that ended about ¾ of a mile east of Cañon City, quickly sent crews to the same area, but were blocked by the Santa Fe workers at the narrow entrance. This was to be the first round in the two-year struggle of the Royal Gorge War.

The D&RG crews tried to leapfrog the other crews but were met with court injunctions from the Santa Fe railroad organization. In an effort to block the Santa Fe they built several stone forts upstream, one of which was Fort DeRemer, at Texas Creek. They harassed Santa Fe work crews and committed several acts of sabotage. They rolled rocks down on the men and threw their tools in the river. Both sides resorted to hiring armed guards for their crews. Soon rifles and pistols accompanied picks and shovels. Both railroads went to court in an effort to establish themselves as having the primary right of way. In April 1879, the D&RG was granted the right to build through the gorge.

Santa Fe announced it would build parallel tracks and compete with existing D&RG lines. Fearing financial ruin, bond holders of D&RG pressured management to lease the tracks to Santa Fe for 30 years. A short-lived truce was established.

To the detriment of merchants in Denver, Santa Fe soon manipulated freight rates south of Denver in favor of shippers from Kansas City over its lines to the east. During this period the Santa Fe constructed the railroad through the Royal Gorge itself. D&RG continued their construction west of the gorge in a continuing effort to block Santa Fe.

After months of shrinking earnings from the leased lines, D&RG went to court to break the lease. A court injunction restraining Santa Fe from operation on the D&RG lines on June 10, 1879 sparked an armed retaking of the railroad by Denver & Rio Grande crews. Bullets flew, trains were commandeered, and depots and engine houses were under siege.

While lawyers argued both sides in court, armed men hired by Santa Fe took control of Rio Grande stations from Denver to Cañon City. They hired the legendary W.B. “Bat” Masterson, a sheriff in Ford County, Kansas at the time, to assemble a group of men to defend their interests. Some sources allege Santa Fe used its political influence to obtain a U.S. Marshall’s appointment for him so he could legally defend their property. Masterson enlisted the help of J.H. “Doc” Holliday to find recruits. Among the sixty or so hired were two gunfighters with the colorful names of “Dirty” Dave Rudabaugh and “Mysterious” Dave Mather. Gunman Ben Thompson, reported to be a personal friend of Masterson, was also recruited. Holliday tried to recruit his friend, entertainer Eddy Foy, who declined on the grounds he couldn’t hit anything with a gun. The group held the key position of defense at the Santa Fe round house in Pueblo.

In June of 1879, R.F. Weitbrec, treasurer of the D&RG, suggested to Chief Engineer J. A. McMurtrie, Sheriff Henly R. Price, and his deputy, Pat Desmond, that they “borrow” the cannon from the state armory as a way to drive Masterson and his men from the roundhouse. To their surprise and dismay, the group found that Masterson had already “borrowed” the cannon and had it at the roundhouse trained on the line of attackers.

[InContentAdTwo]

Weitbrec assembled a group of gunmen. They stormed the telegraph office on the railroad platform and drove the defenders out the back windows, where, it is said, Henry Jenkins, the only causality of the war, was shot in the back by a drunken Rio Grande guard. They then turned their full attention to the roundhouse.

With the cannon trained on them, Weitbrec met with Masterson, who then surrendered the roundhouse.

Masterson was later criticized for his actions and rumors flew that he and his men had been paid as much as $25,000 to surrender. The probable truth is he surrendered after seeing the court order proving the D&RG held the right of way through the gorge.

A final peace was established after the intervention of the Federal courts. The railroad “robber baron” Jay Gould agreed to loan the D&RG $400,000 while announcing the intention to complete a rail line in competition with the Santa Fe from St. Louis to Pueblo.

On March 27, 1880, both railroads signed what was called the Treaty of Boston, which settled all litigation and gave the D&RG back its railroad. D&RG paid Santa Fe $1.8 million for the rail line it had built in the gorge, the grading it had completed, materials on hand, and interest. The Royal Gorge War was over.

D&RG resumed construction and the rails finally reached Leadville on July 20, 1880.

An interesting facet of the construction in the gorge is the hanging bridge at the point where the gorge narrows to about 30 feet. At this point, the railroad had to be suspended over the river on the north side of the gorge, as sheer rock walls go almost straight down into the river. C. Shallor Smith, an engineer from Kansas, designed a 175-foot plate girder suspended on one side by A-frame girders spanning the river. It was anchored to the sheer rock walls. The bridge, when built in 1879, cost $11,759, a kingly sum at the time. In today’s economy, it would cost an estimated $20 million. It was strengthened over time, and has served the rail line for almost 130 years.

Passenger service through the gorge began in 1880 and ended in July 1967. Freight service continued until 1989 when the company merged with Southern Pacific Railroad, who took control of the gorge in their name. In 1996 that combined company merged with Union Pacific Railroad. The year after that merger, Union Pacific closed the route through the gorge.

In 1998, two new corporations, Cañon City & Royal Gorge Railroad (dba Royal Gorge Route Railroad, RGRR) and Rock and Rail, Inc. (R&R), joined to form Royal Gorge Express LLC. The company was awarded the bid from the Colorado Office of Economic Development to purchase 12 miles of track through the Royal Gorge from the Union Pacific to preserve the rail corridor for passenger and freight service.

Passenger service began in May 1999 with five coach cars and one class of service. The coaches in use today are restored 1953-1954 Canadian National Railway cars used on the transcontinental routes throughout Canada. In 2005 and 2006 the RGRR purchased four full-length glass topped dome cars from Holland America Cruise lines in Alaska. After updating they were put into service through the gorge providing a comfortable and climate-controlled view of the gorge while enjoying a full service bar and gourmet menu items. Today there are six classes of service to choose from, including the Murder Mystery dinner train and the opportunity to ride in the cab with the engineer.

The RGRR runs a number of locomotives, including two F-7 class, numbered 402 and 403, that were built in 1949 and 1950 for the Chicago & Northwestern Railway as freight engines. They were later rebuilt for faster commuter service, and were eventually purchased from Union Pacific for the Royal Gorge Route.

The RGRR is a major attraction, carrying over 100,000 visitors and railroad enthusiasts annually on a two-hour, 24-mile round trip historic and scenic ride through the gorge.

Passing under the famed Royal Gorge Bridge towering 1,053 feet above the tracks, the RGRR offers an opportunity to view nature up close and personal while preserving a vital part of Colorado history.

Judy Suchan lives and writes in Cotopaxi, CO.