by Duane Vandenbusche

The year was 1878 and prospectors R.E. McBride and the Boon brothers, unable to get good mining claims at Monarch, east of the Continental Divide, headed west. The three men went up a gulch past Waterdog Lakes, crossed the Divide and descended into the upper Tomichi drainage on the Western Slope. There, the men found good silver ore and filed claims. The following May, over 200 men swarmed into the area and uncovered the rich North Star, Eureka, Carbonate King and May-Mazeppa silver mines.

During 1879, all supplies had to come in via jack train from Monarch over Old, Old Monarch Pass. By May 1, 1880, the Monarch Toll Road was completed and a fledgling mining camp called White Pine was laid out along Tomichi Creek. The new camp was named for the dense growth of pines which covered the surrounding mountains. The two major routes into the camp were from Monarch on the Eastern Slope and Sargents on the Western Slope.

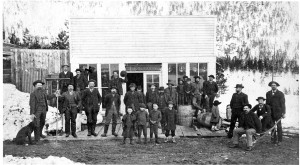

By 1883, White Pine had a post office, the White Pine Cone newspaper, daily stages arriving from Monarch and Sargents and 1,000 miners in the camp and nearby hills. The Horseshoe Saloon, twenty-five by fifty feet and containing a pool table and five round tables for gambling, was the center of attraction in the camp. George Root, editor of the White Pine Cone recalled: “The camp was booming. New faces came in on every stage. Scarcely an hour of the day passed without hearing the creaking of heavily loaded ore wagons passing down Main Street or returning from the railroad laden with goods for the camp.”

By 1884 the boom peaked. White Pine then boasted five stores, three saloons, two livery stables, three hotels – The Crawford House, White Pine Hotel, and Cummings House – meat market, and photographic gallery. Two sawmills worked frantically to meet an ever-increasing demand for lumber and shingles.

The location of White Pine was not desirable. George Root declared: “There was scarcely enough level ground in the camp for more than six or seven town lots. The back yards of the lots on the west side of Main Street were from 50 to 75 feet higher than at street level, while the rear of those on the east side were from ten to 40 feet lower in the front.” Main Street was three quarters of a mile long and “not quite as crooked as a dog’s hind leg.” Huge boulders dotted Main Street, and stages had to run a slalom course to avoid them. George Root summed up White Pine’s location: “As the mines could not be brought any closer, the town was started as near the mines as practicable.”

Dark clouds appeared over White Pine in 1885. The mines were not rich, transportation was difficult, and the price of silver was way down. When the Silver Panic of 1893 hit, White Pine became a ghost town. However, the Akron Mining Company bought most of the mines in 1902 and drove the Akron Tunnel 4,000 feet into Lake Hill, tapping rich veins of coal and zinc. During World War I, the company took out a million dollars of ore for the war effort.

In 1930, the Callahan Lead-Zinc Company bought out Akron, and during World War II engaged in round-the-clock mining to provide badly needed lead, zinc, and copper for the U.S. By 1944 it was like old times in White Pine, with mining going full-blast and over fifty men employed. The town was rebuilt to provide living quarters for the miners. A huge flotation mill was built in 1947, and mining continued until 1953 when falling prices and a lack of demand for ore closed White Pine for good.

During the late 1940s and early 50s the Callahan Mining Company built a rope tow just below town with a 300’ vertical drop for miners and their children – one of the few ski areas in Colorado. White Pine was also unique for its famed “Liberty Bell” – a perfect liberty bell of yellow aspen in the fall of the year surrounded by evergreens.

Today only a few people live in White Pine during the summer. Only a creaking of the majestic pines and the aging cabins remind us today that a great mining camp once existed in the shadows of the Continental Divide.

Duane Vandenbusche has been a professor of history at Western State College since 1962 and is the author of the book Around Monarch Pass from Arcadia Publishing.

I was hoping Duane might have some more information about the numerous avalanches that occured in White Pine, I teach a fourth grader who is writing a report and the avalanches are part of the report. Thanks and hope to hear from you soon.