By Mike Rosso

The Rainbow Trail, which celebrates its 101st birthday this year, could well be seen as an allegory for the various uses and controversies surrounding Colorado forest lands over the past century.

At just over 101 miles long, it spans four counties – Saguache, Chaffee, Fremont and Custer – and ends at the Huerfano County border.

Along its length, outdoor enthusiasts can access numerous 14,000 foot peaks, including Kit Carson (14,165’) and Crestone Peak (14,294’), and over a dozen alpine lakes. The Trail has an average elevation of 9,000 feet and winds in and out of thick spruce forests and aspen groves, as well as high mountain meadows. What initially began as a foot and horseback trail is now accessible to mountain bikes, motorcycles and, for the entire stretch in Custer County, all-terrain vehicles.

The Trail is said to have derived its name from its arc-like shape as it parallels the eastern flank of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains, although views of rainbows across the mountain valleys in the spring and summer are not uncommon. It also hosts a variety of wildflowers, the colors of which rival a painter’s easel.

On its southern end, the Trail lies above where Lieutenant Zebulon Pike, Jr. and his corps encountered the worst weather conditions of their Louisiana Purchase expedition and a near mutiny from January 25-26 in 1807.

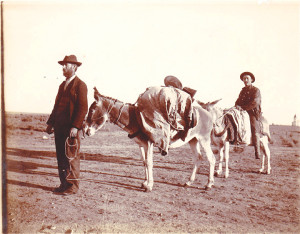

The earliest accounts put the initial Rainbow construction beginning in 1912 and completed by 1930. The San Isabel National Forest was established in 1912 with offices in Westcliffe and La Veta. An early photograph belonging to the West Custer County Library shows two men, Roy Lapsley and Will Falkenberg, with an inscription on the back designating them as “Builders of the Rainbow Trail.” Initially the Trail was built to provide easier access for cattle to high mountain meadows and to gain easier access for fishing the high mountain lakes, many of which already had primitive trails leading to them. Another use of the Trail was horseback wildfire patrol.

An article from the May 1924 issue of the Wet Mountain Tribune describes the maintenance and construction of trails in the Sangres, with an allotment of $9,015 going toward the forest road department of the San Isabel National Forest, $3,310 of which was appropriated for the “making” of nine new trails, including Hayden Pass, Lilly Lake, Sangre de Cristo and the Rainbow Trail, all in an effort to create connecting links in the forest trail system for “both hikers and those who travel by saddle.”

Another article from the Tribune of the same year goes on to describe “seven miles of the new Rainbow trail” going “northwest and southeast from the American Legion campground” intersecting “all the trails going to the fifteen or more lakes in that region. Eventually the trail will reach from Salida to Mt. Blanca and will be 100 miles in length. In several places it runs down to connect with farmhouses for the convenience of travelers.”

A comprehensive account of the construction of the Trail is found in an oral history of Custer County native Archie D. Hess, conducted in 1967. Mr. Hess began working on trails for the government in 1919 and was foreman of the Rainbow Trail project from 1928-29. His sons Archie Jr. and Ray Hess also worked alongside their father on the Trail. In the interview, he states he first began work on the Rainbow in 1925 near the Alvarado ranger station. In those days, remote ranger guard stations dotted the forests managed by the U.S. Forest Service at 20-mile intervals. Fritz Polk was the forest supervisor at the time and Hess speaks of initially working alongside William “Bill” Falkenberg, a man he describes as “one of the most wonderful lovers of nature, and a nature’s gentleman, that I ever knew.”

Hess managed a crew of 10 to 12 men, camping out at night at lakes or alongside streams, dining on fresh-caught trout, and descending in the morning to the Trail where they employed axes, saws, picks, long bars, and one-bladed grubbing hoes (Hess refers to them as “hoe-daddies”), as well as dynamite for “blowing out stumps and rocks.” Crews would work in pairs. Hess describes them as “two men that could get along together and liked the same grub … there was no such thing then as a sleeping bag, it hadn’t been heard of, so the two pair would work together and eat together and sleep together and it, well, made things more harmonious around the camp to work ‘em in that way.” Trail work began around mid-May or early June and lasted until, as Hess described, “the snow would run us out,” usually around early October.

The crews would move their camps about two miles beyond completed sections of the Trail and then work back to connect the new sections, repeating this process until the Trail was completed. Hess and another worker would start out ahead and survey the routes. They were provided maps showing the limits of the deeded land, as well as the forest boundaries. Along with these were instructions from the rangers who, according to Hess, “really were supposed to do the laying out.” They were allowed a maximum grade of 15 percent, and made the trail about 16 to 20 inches wide, leveling it as they went with their grubbing hoes. Traveling back and forth to camp would help level the trail as the men worked. They installed water bars made of rocks or logs to prevent erosion. Every spring, a new crew would go over the Trail, hauling out rocks that emerged, cutting downed trees, swamping aspen seedlings and so forth.

Hess kept a journal of the work accomplished, describing how much trail would get built in a day. “On May 26, 1927, with five men, we completed 225 yards of trail, and used seven shots with 15 sticks of dynamite, blowin’ out rocks. And on the 27th, we built 240 yards of trail.” After working on the Rainbow, the crews then focused their energies on the trails leading up to the lakes.

At the time of the interview, there was talk of turning the entire Rainbow Trail into a motorized road, clear across its length. Hess suggested it would be a better use of federal funds than the war in Vietnam or sending a man to the moon – he was more concerned with limiting motorized use on the lake trails, which were more susceptible to erosion. He thought a motorized route paralleling the Rainbow might be great to give folks access for camping, “to enjoy the forest and have a wonderful time.”

Forest Service records suggest the Trail was improved sometime in the late 1930s by crews from the Civilian Conservation Corps, possibly CCC Company 2134, stationed at Gardner, Colorado. The CCC was a public relief program created as part of the New Deal by President Franklin D. Roosevelt to assist unemployed, unmarried men, providing unskilled manual labor jobs related to the conservation and development of natural resources.

Courtesy of the West Custer County Library.

Forest Service personnel who maintain and patrol the Trail have found no remaining features indicating CCC work, such as bridges and rock retaining walls, and no specific Forest Service records of CCC involvement were found at the San Isabel National Forest Supervisors Office. However, there was a CCC building and camp located near the present-day Alpine Lodge southwest of Westcliffe, which was later acquired by the Holy Cross Abbey in Cañon City, renamed Abbot’s Lodge, and used as a boys’ summer camp for a while. Sometime in the 1980s it was burned to the ground by the USFS, after it had been abandoned for some time.

Over the years, recreational interest in the Rainbow Trail, as well as many trails in the Colorado mountains, grew. From 1950-1960, the Sangres saw a 319 percent increase in recreational use. Backpacking and hiking became more popular, as well as fishing in alpine lakes. Along with this popularity came more impact, usually to the detriment of the forest. Fire rings, trash, trail erosion – all became synonymous with the great outdoors in the mountains. Overgrazing by sheep and cattle, partially due to the easier access created by the trail, was an unintended consequence of its construction.

In 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed the Wilderness Act, creating the National Wilderness Preservation System. The Act created a legal definition of wilderness in the U.S. and immediately created protection for 9.1 million acres of federal land. The Act defined wilderness thus: “A wilderness, in contrast with those areas where man and his own works dominate the landscape, is hereby recognized as an area where the earth and community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.” Federal land in the Sangre de Cristo Mountains was not given wilderness status at that time.

From 1966-68, former Chaffee County Commissioner Jerry Mallett was a volunteer for the Colorado Open Space Council Wilderness Workshops. During his time there, the first review of Forest Service roadless lands, the “Roadless Area Review and Evaluation” or “RARE 1,” was started in 1967. Studies were undertaken to determine additional federal lands that might be considered for wilderness designation. Mallett then went to work for the Wilderness Society, a member of which, Howard Zahniser, had actually written the Wilderness Act. He was sent into the northern Sangre de Cristos, where he spent a summer mapping potential areas for wilderness designation. The Rainbow Trail fell within the boundaries in his final recommendations. Not long afterwards, the RARE 1 recommendations were abandoned after a court ruled the Forest Service had not sufficiently complied with the regulations of the National Environmental Policy Act.

Another roadless inventory was compiled in 1977, RARE 2, recommending nearly 15,000,000 acres for wilderness designation. This also was overruled by the courts.

[InContentAdTwo]

In 1980, Colorado Senator Tim Wirth proposed the Colorado Wilderness Act which, among other areas, suggested wilderness designation for the Sangre De Cristos based on Mallett’s mapping. About 6-8 percent of the recommendations had been removed from his proposal, including the Rainbow Trail, which at the time was beginning to see more use by off-road motorcycles.

In 1993, 26 years after Mallett trekked around the Sangres with his maps, the United States Congress, under President Bill Clinton, designated the Sangre de Cristo Wilderness, setting aside 220,803 acres bordering the Great Sand Dunes National Park and Preserve to the west. The Rainbow Trail was not included in the designation, but much of the wilderness boundary lies 100 feet above large sections of the Trail today.

The Trail history isn’t without some glitches. About one quarter mile of the Trail was constructed on private property belonging to longtime Howard ranchers, the Canterbury family. This didn’t create much of a problem until the trail was opened up to motorcycles. Then, beginning in the 1970s, some dirtbike riders began to enter and exit the Trail across the Canterbury property. Sometimes they would even harass the cow herds and tear up the pasture. Once, the elder Bill Canterbury caught one of the miscreant riders, a newcomer from Texas, and drained his gas tank, flattened his tires and made him walk his bike home. Bill got there ahead of him and explained his actions to the father of the cyclist. The kid never trespassed again. Eventually it became enough of a problem that a representative of the Forest Service with a surveyor’s chain came up to the ranch and did an informal survey of the property. The trail was then relocated onto Forest Service and a fence was erected to keep the cows in and the trail users out.

Motorized use has been controversial since it was first allowed on the trail in the 1970s. Conflict between the various users has tested the adage of “getting along.” ATV use skyrocketed after the machines first came on the scene in the 1990s, removing much of the peace that those “lovers of nature” frequenting the Trail seek out. The ATV use was included in a Forest Service Management Plan, as much of the trail in Custer County is two-track, versus one-track on the northern end. Non-motorized users do find solace in the fact that most trails leading off the Rainbow are non-motorized, with easy access to designated wilderness areas.

In 2011, the Duckett Creek fire ravaged an area outside Hillside, Colorado, forcing the evacuation of the Rainbow Trail Lutheran Camp (see story on page 19) burning about 5,000 acres of forest land surrounding the Trail. Current trail users can easily spot the results of the conflagration, which ended up sparing the camp.

Until 1978, the Rainbow Trail ended (or began) on Methodist Mountain outside Salida. It was the Jimmy Carter era in Washington D.C., and internal funds for trail building were still flowing at the USFS. Ten percent of all cattle grazing fees were funneled back into USFS coffers for roads and trails. Salida native Andy Hutchinson remembered working on the trail crew for then-supervisor Mike Lloyd, spending two summers expanding the Rainbow Trail north, first to Sand Gulch, and then on to Mears Junction at Poncha Pass. Hutchinson also recalled that Youth Conservation Corps members were also employed on the expansion. Barney Lyons, District Ranger for the Forest Service from 1977-79, believes it was then expanded further in the early 1980s to hook up with Silver Creek. Part of the Forest Service mission in those days was to connect existing trails, and this extension would also allow the Rainbow to connect to the Colorado Trail – still under construction at the time.

In the early 1990s, the Rainbow Trail was expanded at the southern end, connecting Music Pass and Grape Creek to South Muddy Road along an old wagon path that connects to Medano Pass in Huerfano County. In 2010, work began on the Little Rainbow Trail, located on Bureau of Land Management property, by private individuals looking for all-season terrain for mountain biking and hiking.

Whatever the future brings – more fires, beetle-kill, news ways to burn fossil fuels on the trail, even the dissolution of the USFS under some draconian future administration – the Rainbow Trail will survive to escort thousands of bipeds and four-leggeds as it meanders along beneath the Sangre de Cristo Mountains for the next 101 years.

Author’s note: Many thanks to Amy Moulton and the great staff at the West Custer County Library; Laura Ruttum Senturia, library director at the Stephen H. Hart Library & Research Center, History Colorado; Sue Cochran from the Royal Gorge Regional Museum; Jim Little; Paul Bosanko; Jerry Mallett, and Tom Wolf, author of “Colorado’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains.”

Accessing information from USFS officials often felt like herding cats – while blindfolded – but we would like to thank the following former and current Forest Service employees for their help with this article: Brett Beasley, Ann Ewing, Catherine Kamke, Barbara Timock, Mike Sugaski, Andy Hutchinson, Mike Lloyd, Jim Free, Barney Lyons, Bill Schuckert and Rod Lewis.