Article by Ed Quillen

History – March 2007 – Colorado Central Magazine

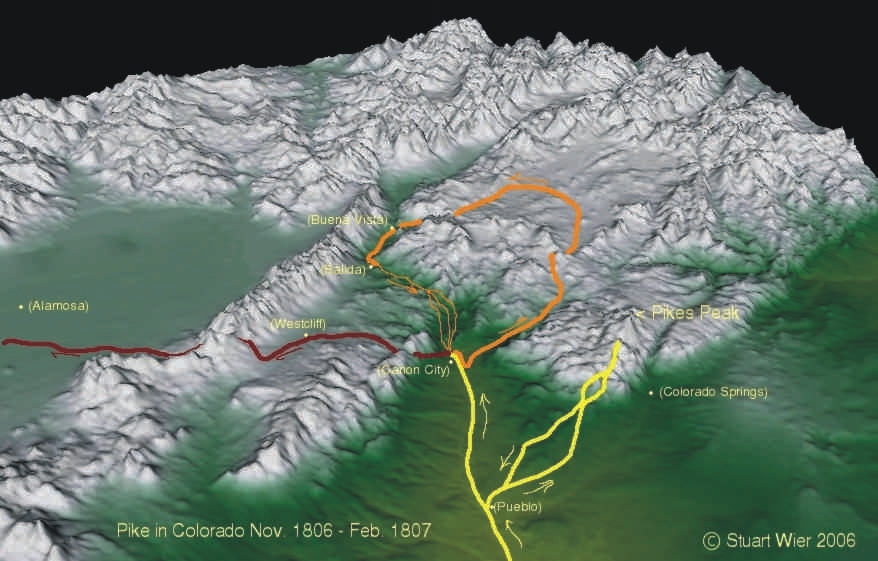

WHEN WE LEFT Zebulon Montgomery Pike on Feb. 28, 1807, he had just departed from Colorado. He and six privates were in the company of Spanish soldiers who were escorting him to the provincial capital of Santa Fé from his stockade southwest of Alamosa in the San Luis Valley.

Dr. John Hamilton Robinson, one civilian who traveled with Pike, was already in Santa Fé. The rest of the Pike party was strung along more than a hundred miles of snowy rough country.

Baronet Vasquez, the other civilian, was the translator. He was in Cañon City with Private Patrick Smith, where they kept the horses and much of the expedition’s non-essential equipment, like formal uniforms and Indian presents — the plan had been for Pike to find a route to the Red River, then come back for the horses, gear, and men left along the trail.

Privates Thomas Dougherty and John Sparks, both with frostbitten feet and unable to walk, were camped at Horn Creek in the Wet Mountain Valley. Hugh Menaugh, left in Huerfano Park on the east side of Medano Pass in January because he could walk no farther, had been brought to the stockade by a rescue party headed by Corporal Jeremiah Jackson on Feb. 18. Jackson had also reached Doughtery and Sparks, assuring them that they would be rescued.

On Feb. 19, Pike had dispatched Sergeant William E. Meek and Private Theodore Miller to head back to Vasquez and Smith in Cañon City. There they were to assemble the horses — now presumably rested and in shape for travel — and pack the gear, pick up Dougherty and Sparks on the way back, and join the others at the stockade where they would build boats and float home down the Red River.

But on Feb. 26, Pike had learned he was really camped in Rio Grande drainage. The Spanish soldiers wanted him to go with them right away, but Pike wanted to wait until his command was re-united at the stockade. Lieutenant Don Ignatio Saltelo said they didn’t have enough supplies to wait that long.

Pike left Corporal Jackson and Private Jacob Carter at the stockade to receive the Meek party when it returned from Cañon City. A small Spanish force would remain, to escort them all to Santa Fé. They arrived after Pike left, and the divided American expedition was never re-united, although Pike kept in touch with Vasquez in later years.

So on March 1, 1807, we have Pike and six privates being escorted to Santa Fé, roughly following the modern route of U.S. 285.

Pike’s legal status is somewhat unclear. He was an American officer who had been found on Spanish soil. He was not a prisoner of war, because Spain and the United States were not at war (though a conflict threatened). He was not a prisoner, because he was not accused of any crime. Even if he was engaged in a variety of espionage, he was not a spy, since he freely admitted that he was a soldier.

AFTER CAMPING TWO NIGHTS, they reached Ojo Caliente on March 1. That night, Pike slept under a roof for the first time since July 22, 1806. He described the roofs of the village as “flat on top, or with extremely little ascent on one side, where there are spouts to carry off the water of the melting snow and rain when it falls, which we were informed, had been but once in two years.” Drought in the Southwest is nothing new, in other words.

The Americans were welcomed with a fandango that night. The next day, as they passed through villages, “We were frequently stopped by the women, who invited us into their houses to eat; and in every place where we halted a moment, there was a contest who should be our hosts. My poor lads who had been frozen, were conducted home by old men, who would cause their daughters to dress their feet; provide their victuals and drink, and at night, gave them the best bed in the house.” One suspects that the “poor lads” may not have slept alone in those beds, but Pike is silent on that matter.

On March 2, they stopped for the night in San Juan, a village a few miles north of Española — which apparently did not exist then, for Pike does not mention hearing any Española jokes.

In San Juan, Pike encountered, of all people, Baptiste LeLande. You may remember that LeLande had owed money to William Morrison, an Illinois merchant, and Morrison had given Pike authority to collect the bill, just in case he ran into a trader along the Red River who knew where to find LeLande. Pike had turned that over to Dr. Robinson in early February when Robinson took off solo from the stockade, hoping to find his way to Santa Fé.

LELANDE ASKED “so many different questions on the mode of my getting into the country, my intention, &c.; that … I was perfectly satisfied of his having been ordered by some person to endeavor to obtain some confession or acknowledgment of sinister designs in my having appeared on the frontiers, and some confidential communications which might implicate me.”

LeLande confessed that this was the case. Pike then dined and wined with his host to the extent of “an immoderate use of the refreshments allowed me,” which “produced an attack of something like the cholera morbus [now known as gastroenteritis, whose symptoms include cramps, diarrhea, and vomiting], which alarmed me considerably and made me determined to be more abstemious in future.” Some things never change, like a hangover producing an “I’ll never do that again” reaction.

Pike’s crew was a rag-tag bunch. “When we left our interpreter and one man on the Arkansaw, we were obliged to carry all our baggage on our backs, consequently that which was the most useful was preferred to the few ornamental parts of dress we possessed. The ammunition claimed our first care, tools secondary, leather, leggings, boots, and mockinsons were the next in consideration; consequently, I left all my uniform, clothing, trunks & c. as did the men … I was dressed in a pair of blue trousers, mockinsons, blanket coat and a cap made of scarlet cloth, lined with fox skins and my poor fellows in leggings, breech cloths and leather coats and not a hat in the whole party.”

ON MARCH 3, they rode through Santa Cruz on their way to Santa Fé, where Pike was escorted to the plaza and the Palace of the Governors, “the floors of which were covered with skins of buffalo, bear, or some other animal.”

There he met Governor Joachim Allencaster. Pike did not speak Spanish, and Allenaster did not speak English. But they both spoke French. Allencaster asked “You come to reconnoitre our country, do you?” “I marched to reconnoitre my own,” Pike replied.

Allencaster was dubious about that, but he was in a delicate position. Here are some foreign soldiers captured in his territory. Their commander says they were lost, but that might be just a cover story. Allencaster is the governor of a poor, remote province of a vast empire whose capital lies in distant Madrid.

If he imprisons or executes Pike, he could provoke a war with the United States — and a decision of that magnitude should not be made by some remote provincial authority. If he has Pike’s party escorted east to the Red River where they said they wanted to go, he’s not exactly protecting the empire, and that could get him into trouble with his superiors. The normal procedure for Americans in New Mexico is to keep them there under something like house arrest (as with the trader James Purcell whom Pike met in Santa Fé), but that would be an affront to military courtesy and perhaps a provocation to war.

So like any competent bureaucrat, Allencaster will cover his ass by sending Pike to Chihuahua, where somebody in a higher pay grade — Nemesio Salcedo, Commander General of the Internal Provinces — can decide what to do with these intruders. Under a military escort, Pike and his men are sent south on March 5.

BUT ALLENCASTER does have some questions for Pike before sending him off. It seems that a few days earlier, another gringo stranger showed up in Santa Fé, a Dr. Robinson. Pike is asked about him, and if he doesn’t lie in his answers, he certainly stretches the truth. Pike admits to knowing him, but says Robinson is not part of his command. That’s sort of true; Robinson was a civilian attached to the expedition, not a soldier under orders in the expedition.

Pike said that because he feared Robinson would be charged as a spy if he were traveling as a civilian and was really under military orders.

Allencaster wanted to see Pike’s papers. Pike presented his commmision and orders, and Allencaster told him he could take his papers, which were in a trunk, back to his quarters. Pike had feared that the Spanish would want his papers, so he took out his maps and the like, and distributed them among his men.

However, “I found that the inhabitants were treating the men with liquor; I was fearful they would become intoxicated and through inadvertancy betray or discover the papers.” Pike was unable to find the man who had the journal that night, however, so it remained in his possession and the Spanish did not take it later. Thus he was able to publish the journal that became a best-seller in 1810. If he’d been able to find that carousing soldier that night, then the journal might have languished in the Spanish archives until their rediscovery in 1910.

Pike and Robinson reconnected on March 7 near “the village of Albuquerque.” Robinson told Pike that on Feb. 7, he had hiked from the stockade up the Conejos River, looking for a divide to take him from the Red River (which they thought they were on) to the Rio Grande (which they were actually on). He met two Indians. Robinson told Pike, “I signified a wish to go to Santa Fé, when they pointed due south, down the river I left you on…. I therefore offered them some presents to conduct me in; they agreed.” Robinson got to Santa Fé two days later, got a chilly reception from Gov. Allencaster, and was sent south where he rejoined Pike.

Pike and company were escorted to Chihuahua by a Spanish soldiers under Lt. Don Facundo Malgares, who had commanded the 1806 campaign to the Pawnee that was supposed to intercept Pike. Had the timing been a little different, the two men would have opposed each other in battle. As it was, they became fairly good friends during Pike’s visit to Mexico, for they had much experience in common. Doubtless Malgares produced reports of both his campaign and his time with Pike, but they have been lost to history, although there’s always hope that they’ll turn up someday in an archive in Mexico City or Seville.

THE OTHER HALF of Pike’s detachment — the men he left in Colorado — eventually arrived at the San Luis Valley stockade, and were sent south on the same route, although the force was never re-united. Pike returned to American soil on June 30, 1807, at Natchitoches, Louisiana Territory.

Only one soldier died on the Pike expedition. The victim was one of the “left-behind” group which was not returned to the United States until 1809. On May 4, 1807, Private Theodore Miller got into a drunken brawl with Sergeant William Meek in Carrizal, Mexico, and Meek stabbed him to death. Meek was consequently imprisoned in Mexico until 1820.

By then, Pike was long dead. He was steadily promoted in the Army; he became a captain during the 1806-07 expedition, but did not find out until his return. By 1813, he was a brigadier general who led the invasion of York (today’s Toronto) during the War of 1812. After the British surrender there, a powder magazine exploded, and a rock struck Pike’s head, killing him.

To commemorate this bicentennial, we’ve been following Pike around since July. Now, since the local celebrations have concluded, these monthly installments will come to an end, too. After all, by the end of March, 1807, Pike and his soldiers had departed Colorado.

[Salida Post Office cancelltion for Pike bicentennial.]

The Pike expedition will always provide some controversy for historians and history buffs: Was he spying? Did he have secret instructions? Was he really lost, or just pretending?

And its significance will always be debated. You can make the argument that his journal inspired the Santa Fé trade and trail, which led to the 1846-48 Mexican War and to the 1861-65 Civil War — certainly a matter of some significance. But you could also argue that the New Mexican trade and the ensuing wars would have happened without Pike.

It is fun to speculate. Suppose Andrew Jackson, victor of the Battle of New Orleans, had died in the War of 1812, and Pike, victor in the Battle of York, had lived? Would Pike, like other victorious generals over the years, have gone on to become President of the United States?

[Stamped postcard in honor of Pike bicentennial]

Another speculation: Suppose that Juan Bautista de Anza had been governor of New Mexico when Pike arrived? How would Anza have reacted? My guess is that Anza, being much more a military man than Allencaster, and also less likely to pass the buck, would have gathered Pike’s men in Santa Fé, and escorted them directly to the Red River. But since Anza died in 1788, when Pike was only nine years old, their paths never crossed.

WHEN PIKE was born in 1779, Anza was moving into the Palace of the Governors. Anza’s success in making war, then peace, with the Comanche allied them with Spain — which may explain why Pike, despite his orders to find the Comanche and treat with them, was never able to meet them. Anza also got along well with the Utes — who found Robinson and headed him toward Santa Fé.

There are some odd coincidences between Pike and Anza. Both were career military men. Both were named for their fathers, and both their fathers were career military men. Both were frontier army officers during their careers. And they provided the first two written accounts of our part of the world — Anza’s came first, but Pike’s was more detailed.

Anyway, it’s been a pleasure to tag along with the Pike expedition during this commemoration of 2006-07.