Article by Ed Quillen

History – February 2007 – Colorado Central Magazine

AT THE END OF January, 1807, Capt. Zebulon M. Pike’s small party was spread out for a hundred miles in the dead of winter. Private Patrick Smith and Baronet Vasquez, the interpreter, had been left on Jan. 14 with the horses and some of the gear at the site of present-day Cañon City. The plan was for the others to press southwest and find a route to the Red River, then return for the men, horses, and gear, and follow that route.

Those who pushed southwest, carrying 70-pound packs, had ascended Grape Creek into the Wet Mountain Valley. Starvation was imminent, and Privates John Sparks and Thomas Dougherty could no longer travel. Their feet were frozen. They were left with most of a buffalo carcass on Jan. 22, and they were supposed to camp until rescue arrived.

The rest of the party crossed the Sangre de Cristo Range, probably at Medano Pass, and during that ordeal, Private Hugh Menaugh was left behind on Jan. 27.

So by Feb. 1, Pike had left five men behind him in three different places, separated by hard miles and bitter weather. His small party was in serious danger — hypothermia and starvation loomed, and Indian attacks were a possibility.

But while coming down Medano Pass in late January, Pike had seen a river emerging from the western mountains — our San Juans — flowing east before it turned south. This just had to be the Red River which he’d been looking for, but it was in fact the Rio Grande. They reached it, marched south along its bank for 18 miles, crossed the river four miles south of present Alamosa, then ascended a tributary, today’s Rio Conejos, until they came to a grove of trees on Jan. 31.

There Pike decided to build a small fort or stockade. There was timber so they could “make transports to descend the river with” — that is, float down the Red River to Louisiana and a return to civilization. Four or five men could hold the fort against Indian attacks, while the other half-dozen went back to fetch their five comrades — if any were still alive.

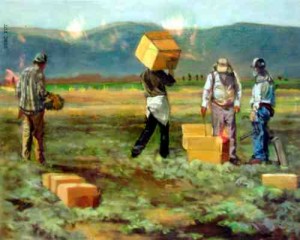

[Reconstruction of Pike’s Stockade in the San Luis Valley. Courtesy National Park Service]

On Feb. 1, they “laid out the place for our works [the stockade], and went hunting.” They didn’t kill anything, but the next day, Pike and Dr. John H. Robinson brought down a deer “with great difficulty … seven or eight miles from camp.”

While the soldiers worked on the stockade, Pike and Robinson hunted and reconnoitered. They climbed a hill, and the view was “one of the most sublime and beautiful inland prospects ever presented to the eyes of man. The prairie [San Luis Valley] lying north and south, was probably 60 miles by 45.

“The main river bursting out of the western mountain, and meeting from the north-east, a large-branch, which divides the chain of mountains, proceeds down the prairie, making many large and beautiful islands, one of which I judge contains 100,000 acres of land, all meadow ground, covered with innumerable herds of deer…. In short, this view combined the sublime and beautiful; the great and lofty mountains covered with eternal snows, seemed to surround the luxuriant vale, crowned with perennial flowers, like a terrestrial paradise, shut out from the view of man.”

PIKE MAKES IT SOUND as though he had wandered into Shangri-La, instead of the San Luis Valley in January. At the time, though, he thought he was near the headwaters of the Red River. And one of his party, Dr. Robinson, wanted to get to the Rio Grande and follow it to Santa Fé. By their reckoning, they were about as close to Santa Fé as they were going to get — the Red would soon have to turn east and take them out of the mountains.

So on Feb. 7, Robinson headed south alone, with Pike planning to recover the rest of his men and build boats for a spring float trip down the Red.

At the time, Spain had done its best to sequester its New World domain; few outsiders ever visited and returned. Most were detained indefinitely.

However, there was a commercial treaty between the United States and Spain allowing the collection of debts, and officially, at least, Robinson was acting under this provision.

To make a long story short, in 1804 an Illinois merchant named William Morrison had sent an agent, Baptiste La Lande, on a trip west to trade with the Indians along the Platte River. Instead of returning with bartered robes and pelts, La Lande made his way to Santa Fé where he set up as a trader, using Morrison’s investment as his stake. So La Lande owed Morrison money, and Morrison understandably wanted to collect — a difficult matter when La Lande was a thousand miles away in a foreign country.

As Pike was about to embark on his expedition in the summer of 1806, “Morrison, conceiving that I might meet some Spanish factors [traders] on the Red river, intrusted me with the claim, in order, if they were acquainted with La Lande, I might negotiate the thing with some of them. When on the frontiers, the idea suggested itself to us of making this claim a pretext for Robinson to visit Santa Fé. We therefore gave it the proper appearance, and he marched for that place. Our views were to gain a knowledge of the country, the prospect of trade, force, etc.”

So there was certainly some element of spying, or at least intelligence-gathering and some chicanery, since Pike observed that the bill-collection paperwork was “in some degree spurious in his [Robinson’s] hands.”

Pike’s orders were to stay out of Santa Fé, and indeed, Spanish territory altogether. Gen. James Wilkinson, his commanding officer, wrote that “you may find yourself approximated to the settlements of New Mexico, and therefore it will be necessary you should move with great circumspection, to keep clear of any Hunting or reconnoitering Parties from that Province, and to prevent alarm or offense, because the affairs of Spain and the United States appear to be on the point of amicable adjustment, and moreover it is the desire of the President to cultivate the Friendship and Harmonious Intercourse of all the Nations of the Earth, and particularly our near Neighbours the Spaniards.”

Robinson clearly wanted to go to Santa Fé. He was not a soldier, but he served as surgeon for Pike’s expedition, and Pike found him good company: “As a gentleman and companion in dangers, difficulties, and hardships, I in particular, and the expedition, owe much to his exertions.” Very little else is known about Robinson, including why he joined the expedition in Missouri.

On Feb. 7, the same day Robinson left for Santa Fé , Pike dispatched Corporal Jeremiah Jackson and four men to go back into the mountains and “bring in the baggage left with the frozen lads, and to see if they were yet able to come in.”

Pike attended to self-education for the next week, “refreshing my memory as to French grammar” on Sunday, “Studying” on Thursday, and always hunting and supervising construction of the stockade.

The confrontation between soldiers at the remotest frontiers of two empires came on Feb. 16. Pike was out hunting with one of the privates; they wounded a deer, and then he “discovered two horsemen rising the summit of a hill, about half a mile to our right.” After some maneuvering and posturing as the parties got closer to each other, Pike hollered “that we were Americans, and friends, which were almost the only two words I knew in the Spanish language.”

THE STRANGERS WERE “a Spanish dragoon [mounted soldier] and a civilized Indian,” armed with lances. “They informed me that was the fourth day since they had left Santa Fé; that Robinson had arrived there, and was received with great kindness by the governor.”

The Spanish emissaries followed Pike back to his stockade, where they spent the night before heading back to Santa Fé. “After their departure, we commenced working at our little work [the stockade], as I thought it probable the governor might dispute my right to descend the Red river, and send out Indians, or some light party to attack us; I therefore determined to be as much prepared to receive them as possible.”

That evening, after more than a week on the trail to fetch the men left behind, Corporal Jackson returned with three men. “They informed me that two men would arrive the next day,” one of them Hugh Menaugh who had been left in the Sangres, “but the other two, Dougherty and Sparks [left in the Wet Mountain Valley], were unable to come. They said that they had hailed them with tears of joy, and were in despair when they again left them, with the chance of never seeing them more. They sent on to me some of the bones taken out of their feet, and conjured me by all that was sacred, not to leave them to perish far from the civilized world.”

Pike had to get his party back together; he knew the Spanish knew his location, and he didn’t know their intentions. On Feb. 19, he dispatched Sergeant William E. Meek and Private Theodore Miller to go back to the Cañon Camp for the two men there and the horses and gear; presumably they could pick up Dougherty and Sparks on the way back, and the command would be re-united.

Meanwhile work continued on the stockade as it got a moat and sharp sticks pointed out over the walls to deter a scaling attack. To get in and out of the stockade, the men had to crawl across a little drawbridge.

The Spanish returned on Feb. 26, although Pike referred to them as “two Frenchmen.” They “informed me that his Excellency, governor Allencaster, had heard it was the intention of the Utah Indians to attack me; had detached an officer with 50 dragoons to come out and protect me; and that they would be here in two days.”

Pike didn’t want to provoke the Spanish, and they didn’t want to provoke him — in sending 100 soldiers, Allencaster said he was protecting Pike, rather than capturing him. Allencaster wanted Pike to come to Santa Fé and explain why American soldiers were on Spanish land.

THE 100 SOLDIERS did not appear in two days — they appeared almost instantly on Feb. 26, armed with “lances, escopates [shotguns], and pistols.”

Pike had no choice but to parley with them, and it was then he learned that he was not on the Red River, but the Rio Grande, and he was trespassing on Spanish soil. “I immediately ordered my flag to be taken down and rolled up,” and he “was conscious that they must have positive orders to take me in.”

Pike wanted to wait until the rest of his men had returned. Lt. Don Ignatio Saltedo said that if they stayed, he would have to send for provisions, but if Pike went with him now, he would leave “an escort of dragoons to conduct the sergeant into Santa Fé.” Pike said he had to leave two men at the stockade to meet Sergeant Meek and his party, or else they would never come in without a fight.

The Spaniards where pleased with this arrangement, but Pike’s men “were fearful of treachery” and “wanted to have a little dust” — apparently a fight, or “dust-up” in more modern slang.

The men mingled, and “the hospitality and goodness” of the Spanish force “began to manifest itself by their producing their provision and giving it to my men, covering them with blankets.”

Pike wrote orders for Corporal Jackson and Private Jacob Carter, who were to remain at the stockade, to pass on to Sergeant Meek when he returned with the rest of the men.

Then “We sallied forth, mounted our horses, and went up the river about 12 miles, to a place where the Spanish officers had made a camp deposit, from whence we sent down mules for our baggage &c.”

On Feb. 28, Pike rode out of what is now Colorado, and into what was then, and still is, New Mexico.