by Mel Strawn

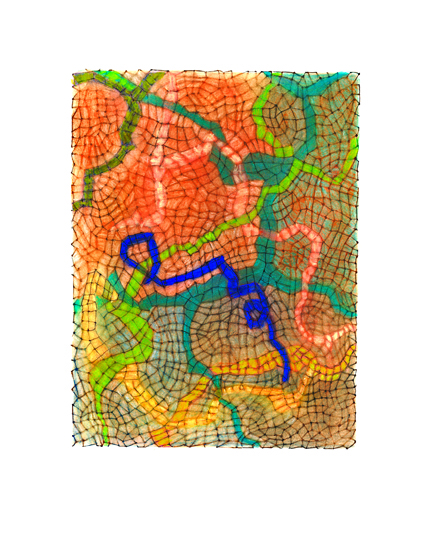

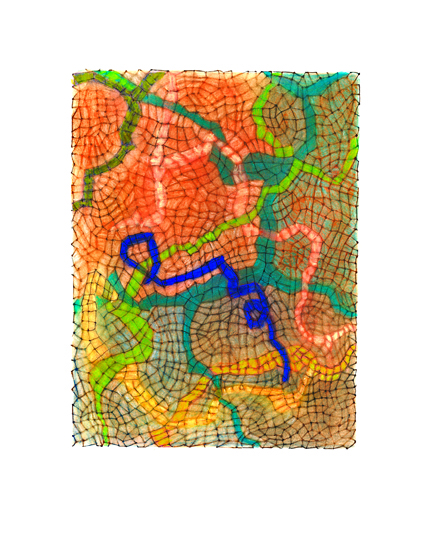

Nets, like webs, are linear systems or networks. Jude Silva’s net drawings completely, evenly and elegantly span rectangles about 13 by 10 inches, filling a 23×15.5” space like patterned gossamer floating within a larger white rectangular world. None, however, are just flat patterns; they are spatial structures tied at nodes, mostly four-way but some with three connecting lines and a few with more. In nature, cracks in drying mud or fractured rock or other elastic materials, typically finds three-way, 120-degree patterns. Our minds impose different norms – often 90-degree oppositions, which also occur in non-elastic materials under stress, like ceramic crackle patterns. These drawings result from mental constructs, not depictions of stress patterns. Each drawing is animated in a different way and dances to its own special tune. A few suggest larger geometric or architectural ambitions. Most, and for me the more interesting, find less geometric rhythms and tensions like Number 15, reproduced here (and part of this month’s cover image). Number 11, also shown here, is more austere, sans color, and offers another of the wide variety of spatial effects shown in the whole series.

How is it that a linear network, essentially just short lines and dots or nodes where the lines join, can constitute an image a “statement,” an expression which can both be thought about and, perhaps simultaneously, be felt?

As an aside: observers who measure such things record that the average time in New York’s Metropolitan Museum spent a mean time of 17 seconds to look at a painting. I’ve not timed folks taking in Jude’s net drawings but, based on intermission audience observations at the April Walden Chamber concert, few take even that long. However, the glowing comments in the guest book show that some did. These are enjoyable works! They are fresh, airy and intriguing. My point is that when viewing an artwork it may well take more than 17 seconds to either think much about or feel anything at all. All the stuff on labels-who did it, media, size, price, etc. – is not what it is primarily about.

These net drawings are complex. They show us the shifts, pulls, compressions, turns, and bends that seem to result from unseen and un-named forces. Like seismographs they show events in space and in time. Our vision is fast, taking in an overall effect or selecting an outstanding detail – snapshots that seem to satisfy. To see these drawings well, however, may take longer. It took time to make the drawings, constructed mark by mark, and our eye takes time to wander through, perhaps skating or surfing along broader, implied surfaces. The movements felt and followed are the ‘events’ perceived. The crisp, tactile quality of the drawn marks, their color and visual weight, binds together into an overall tonal pattern animating the pristine emptiness of space. We are not used to thinking about space itself as an actor, part of the subject and meaning of a work of art. In some few drawings the space behind the nets is colored, a floating tonal atmosphere – as if space itself is playing counterpart to the web of the networked lines and nodes. Although ‘precise’, these drawings are obviously handmade; a nearly imperceptible organic irregularity is in each mark. Mechanically ruled lines, even those beautifully made by an architectural draftsman, would feel different, be faster, cooler; these marks are deliberate and in no straight line hurry to get from node to node-and they are warm.

Such drawings need no words of literal translation; they do not “mean” anything in particular; they are not abstractly coded mysteries; they can neither be justified or dismissed as ‘abstract art’; they simply exist as objects one can experience as one’s own perceptual event. They need no names, but one should feel free to name or interpret them if that comes to mind and pleases. Jude just numbered them.

The genesis of Jude’s drawings lies in her work with fibers and in three dimensions-well, four if we count the essential time factor in both making and perceiving. The cover image is composed of a very real fabric net harboring one of the drawings in its ephemeral and digital center: real net finds a new existence as a composite graphic image.

This is part of “How Is It That – a net drawing can be thought about and felt?”

On another level, if one chooses to bring conscious thought to bear, these net/web drawings may echo our knowing of Polynesian navigation charts made with thin linear strips of wood tied at crucial nodes – the whole structured, net-like pattern a guide to one’s place in the ocean current realm under the stars.

One may think them to be cousins, maybe, of butterfly nets or those used by fishermen always and everywhere. Spiders spin and connect their own strands, sometimes in elegant orbs not too unlike one of Jude’s drawings (#7) – but there is a difference and there are similarities. The spider’s is meant to intercept winged or wind-born meals in its near flat net stretched between limbs or other structures. Jude’s orb-like net visually moves in more three-dimensional space carving an implied bowl or cupola-and in doing so makes us sense the tension between the flat paper on which it is drawn and the feeling of volume and deeper space we perceive; it gives us an image of another form that is not web or net, but a bowl-like volume of space. It may be for some viewers, as it is for me, that a drawing encompasses knowing about orb webs by spiders or other similar phenomenon – but is not dependent on those associations. A subtle thing …

Fences are like nets – keeping things in and keeping them out. Cities, especially seen from several thousand feet above at night, yield visual networks – lights, streets with intersection nodes and overpasses, networked comings and goings sometimes bent by hills and valleys. You will have your own associations, even if not consciously.

Net drawings are quintessentially of connectedness, of touching, binding and of reaching and gathering. They map planes, surfaces that we feel as flat and taut or bending, shifting, twisting – always shaping and always moving on. And, perhaps most importantly, they are experienced as orders, coherent systems influenced by but maintaining themselves in realms of hidden energies. Static as two-dimensional drawings on paper, they are images of an ordered, alive intelligence we subconsciously understand and appreciate.

It is said that ‘art expresses the artist’ or the ‘artist does it to express him/herself’. Part of the story perhaps; Jude Silva is the artist. She makes drawings and nets not as utilitarian objects but as things to look at and contemplate, a different kind of utility on the human scale of values. This is different from ‘looking at’ in order to identify, name and categorize – which is what most viewers like those in the museum survey do. The contemplation can be something like what I’ve discussed above and is different for each viewer. To know the value of these works we have to take the measure of our own experience as we see and contemplate. More could be written about these works but they are more than mere decorations and deserve to be celebrated.

Jude Silva has her studio and lives in Buena Vista with her husband, Jim, who adds photography and astronomy to the family enterprise. Hand-made vessels in fiber and paper, drawings and paintings are part of her larger background and production. She has studied, traveled, taught and worked in the San Francisco Bay area as well as Colorado since the late 1950’s. Jude has a diverse educational background with MA and MFA degrees from San Jose State University. Her very impressive professional record and words of her own can be found on her web site; www.judesilvaartist.com

Mel Strawn has lived in Salida as a practicing artist for 22 years after teaching in colleges and universities for 32 years. His work belongs in collections from the Columbus Museum of Art to the Kirkland Museum in Denver.