By Tina Mitchell

By Tina Mitchell

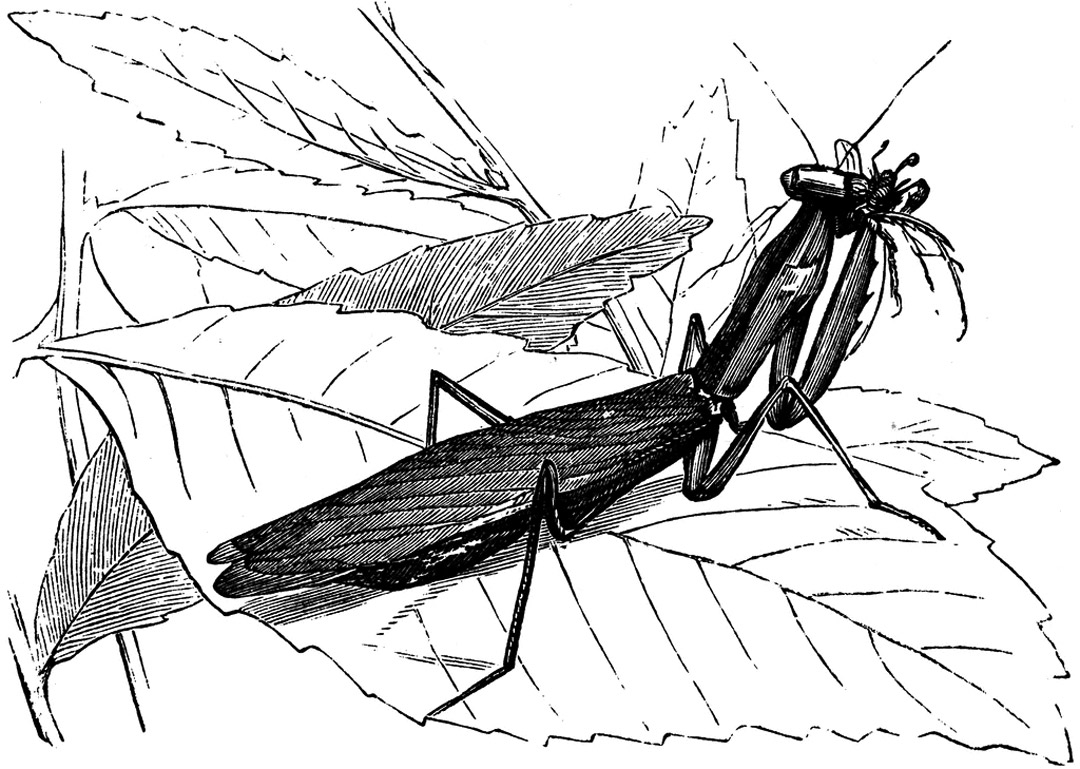

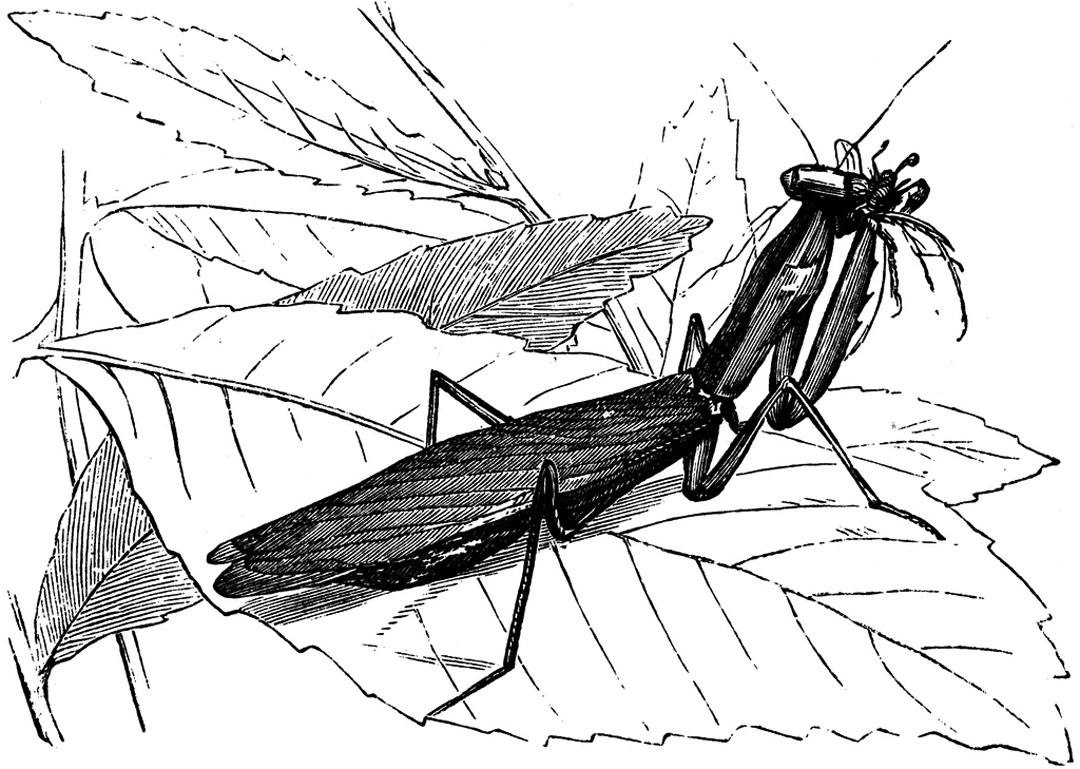

Mantids (for instance, the “praying mantis”) are some of the most distinctive and well-recognized of all the insect groups. The front prey-grasping legs capture everyone’s attention when they spot a mantid. The top of the thorax (the prothorax) is very elongated to support these prominent forelegs. Mantids have excellent vision, with the prominent eyes widely spaced on a triangular head that can twist, providing an almost 360-degree range of view, and a sometimes creepy look.

The terms “mantid” and “mantis” are often used interchangeably. Technically, “mantis” refers only to a member of the genus Mantis. The most widely recognized Mantis is the praying mantis (the European mantid or Mantis religiosa) – a European native now well established in much of Colorado. But any member of the over-arching order of Mantodea (which includes the Mantis genus) can be called a “mantid.” At least six species of mantid, both native and introduced, occur in Colorado. The smallest are two native wingless ground mantids (genus Stigmomantis), found in Colorado’s shortgrass prairie. Next in size are two closely related species, the Carolina and California mantids (genera Litaneutria and Yersiniops), found east and west of the Continental Divide, respectively. Perhaps the most prevalent is the European mantid (genus Mantis), whose most distinctive feature is a bull’s eye pattern under its forelegs. Largest is the Chinese mantid (genus Tenodera), whose egg cases are sometimes sold by nurseries or through mail order, although this mantid rarely survives Colorado’s winters.

Mantids that endure Colorado’s cold winters do so in egg cases (oothecae; singular, ootheca) about one inch long, sometimes containing hundreds of eggs. Under optimum conditions with adequate food, an adult female can produce two or even three oothecae. An insulating cover protects these eggs, resembling Styrofoam packing peanuts. Young mantids (nymphs, which look like very diminutive adults) emerge from the eggs in late spring and feed on tiny flies and other small insects. Following several molts, full-sized adults appear from July through at least September.

Among the giants of the insect world, these fierce predators hunt by stealth, waiting with Zen-like stillness in the grass or moving slowly until they finally pounce upon their prey. Their large, widely spaced eyes provide keen vision (for an insect) that can detect depth of field – useful for assessing potential prey. Large, curved front legs allow them to capture and hold almost any insects that come within reach.

[InContentAdTwo] By the standard food chain sequencing, insects feed on plants or one another, and birds then hunt down insects. But mantids flip that order, preying on hummingbirds and other tiny-to-mid-sized birds more often than most people realize. Researchers at Louisiana State University’s Museum of Natural Science documented 147 cases of mantis-on-bird predation in 13 countries. All species of hummingbirds served as the most common targets in the U.S. In other countries, warblers, sunbirds, honeyeaters, flycatchers and vireos appeared on the mantid menu. Large species such as the Chinese mantid, which can grow to four inches in length, were the most avid avivores, with females responsible for virtually all the bird-killing. Sometimes a mantid would feast on the bird’s flight muscles along the keel (breastbone). But more often it went for the head, especially the brain. (“Hummingbird brain – it’s what’s for dinner.”) I can personally attest that mantids learn to hang out near, even on, nectar feeders, signifying at least some level of cognition. More than once, I’ve observed one slowly stalk the hummers at my feeder. As I walk to the feeder to escort the mantid off to another part of the garden, I feel grateful that mantids aren’t our size.

Although most adult mantids have wings, they can also jump unerringly. Bending its abdomen and making an intricate series of twists and turns with its legs, a mantid ensures a flawless landing on even an absurdly challenging target nearly every time. When researchers held a pencil vertically in front of a mantid at just the right distance, it would leap onto the pencil without fail. The abdomen’s bending was especially critical. When the researchers used a glue to stiffen the abdomen, the mantid could not curl it properly and the insect invariably missed – sometimes even face-planting on the target and falling to the ground.

And in some world, somewhere, somehow, a hummingbird smiles.

After a quarter-century in Colorado, Tina and her family recently migrated to Southern California, where she’ll spend the next quarter-century trying to remember that the mountains lie to the east.