By Tina Mitchell

As we hiked above treeline, the path took a right turn and our ears filled with high-pitched, squeezed-dog-toy squeaks. The dogs snapped to attention, so we made sure we had them on short leashes. We had entered the realm of American Pikas.

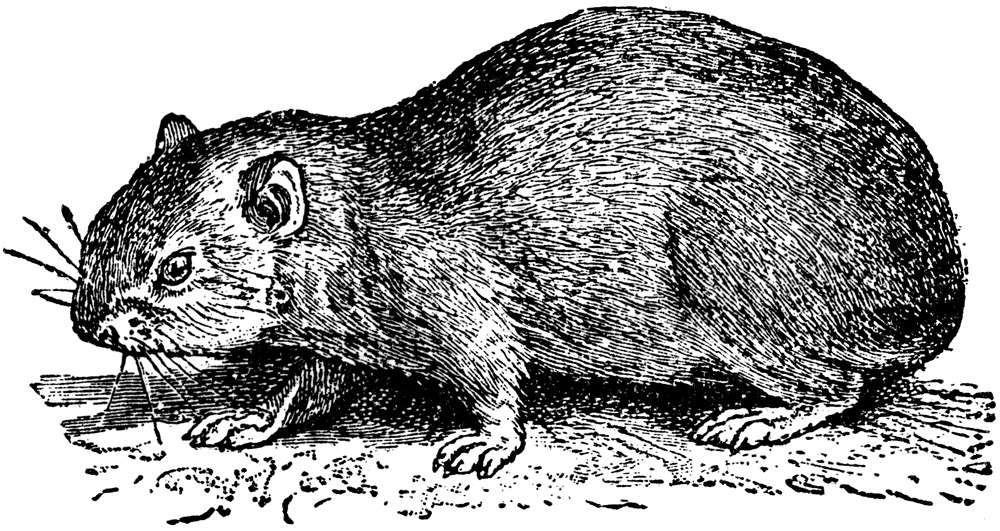

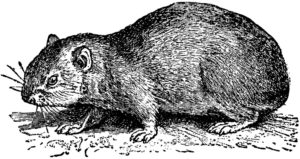

Small mammals related to rabbits and other lagomorphs (even though they look more like big hamsters), American Pikas (pronounced “PIE-kah”; Ochotona princeps) are cuddly-looking, pocket-sized mammals with oval bodies only about six inches long, moderately large rounded ears, and no visible tail. Their sharp, curved claws and padded toes help them easily scamper around alpine rocks. Their voices clearly announce their presence; but camouflaged against the boulders, these spritely creatures prove more difficult to see.

At least 30 species of pikas live throughout the world. Most inhabit mountainous areas of Asia, but two live in North America – the Collared Pika (O. collaris), in Alaska and Canada, and the American Pika, found throughout the high western mountains of North America. The genus name Ochotona stems from ochodona, the Mongolian word for pikas. The species name princeps, from the Latin word for “chief,” refers to a tribal name for the pika: “little chief hare.” Pika is the word used for these animals by the Tunguses tribe of northeast Siberia.

In Colorado, pikas call the lower portions of rocky talus slopes above 11,000 feet home. They live in colonies often connected by tunnels. Fed by moisture trapped under the talus, nearby lush mountain meadows provide food. American Pikas have adapted to a very narrow set of living conditions. Temperatures above 80° F for more than six hours can be lethal if they cannot escape the heat. They do not hibernate in the winter but instead rely on the insulating effects of deep snowpack to avoid freezing. Too little snow, as has been happening in some mountain areas, and pikas may freeze.

Pikas are herbivores, spending the short alpine summer frantically gathering food (e.g., wildflowers, grasses, sedges) into stashes or “hay piles” to sustain themselves through the winter. This frenzied activity consists of stuffing large quantities of plants into their mouths– stalks sticking out of both sides of their mouths, resembling unruly moustaches – and scurrying to designated storage areas to let the plants dry. During a 10-week summer, one pika can make as many as 14,000 foraging trips to secure its food stash, which averages more than 60 pounds.

The adaptations that allow this species to thrive in these harsh environments also make it vulnerable to a changing climate. With their limited range and sensitivity to warm temperatures, pikas appear destined to join the pantheon of wildlife doomed by climate change – driven ever higher, until they’re eventually pushed off the tops of their mountains and into oblivion.

[InContentAdTwo] But the relationship between pikas and climate change seems more complicated than expected. Many populations in the Rocky and Sierra Nevada Mountains have actually held their ground. At the hottest times of day, the shaded chambers between the rocks can be as much as 12° F cooler than the talus surface. In fact, these chambers often consistently stay cooler than the average air temperatures. Such refugia, where local climate conditions defy regional trends, can be found in the nooks and crannies of almost any landscape. Cold-air pooling – cool, dense air flowing downhill to collect in low areas – and the ability to retain moisture are the basics of refugia. While pikas may be able to adapt to heat thanks to refugia, extremely cold temperatures could prove more challenging. If climate change leads to lighter, less insulating snowpacks, pikas will be exposed to cold they can neither escape nor survive.

For now, though, refugia offer a rare glimmer of hope for those working to save the American Pika. They probably won’t last forever, though. If warming continues unabated, these places will eventually grow too hot or too dry also. But the focus on protecting and enhancing refugia beats doing nothing. While managers work to come up with long-term climate adaptation plans, such interim strategies buy valuable time for these squeaking, perpetual-motion “leprechauns of the high country.” And if you hike with canine buddies, keep them tethered to you around alpine talus slopes. Life provides enough challenges for pikas without having to dodge our four-legged companions too.

After a quarter-century in Colorado, Tina and her family recently migrated to Southern California, where she’ll spend the next quarter-century trying to remember that the mountains lie to the east.