By Daniel Smith

Seared into his memory, Bill Reeves remembers the moment:

“Soon the downdraft pushed us below the clouds, just enough to where I could see pine trees off our left wing tip fairly closely, and looked ahead and there was a ridge coming at us. I said ‘ridge’ and ‘turn’ and Wil turned left … and that put us into the Stout Creek drainage where he was trying to outclimb terrain in a downdraft. And so as we came down in, you know what I was seeing at that point was just rocky, bouldery walls everywhere and starting to think ‘this is it, you know, we’re not going to make it,’ and starting to figure out where I was going to hit.”

That harrowing moment has a direct link back to the story we reported in the last issue: the 1995 murder case involving victim Richard Johnson and his later-convicted killer, Jeremy Denison, a case involving drugs, an informant and a controversial trial. Denison is serving life without parole for cutting Johnson’s throat in January of that year.

About two weeks after the murder this next tale unfolds. Johnson’s body was to be returned to relatives for burial in Utah, and local pilots Wil Atkinson and Bill Reeves were en route to deliver the body to Cortez from Salida on Feb. 8, when weather and fate intervened, turning what should have been a routine flight and return into a dramatic struggle for survival against formidable odds.

Johnson’s body was to be returned to relatives for burial in Utah, and local pilots Wil Atkinson and Bill Reeves were en route to deliver the body to Cortez from Salida on Feb. 8, when weather and fate intervened, turning what should have been a routine flight and return into a dramatic struggle for survival against formidable odds.

An introspective and affable man, Reeves still today walks in the shadow of what happened to him and his close friend, and was forever changed by it.

Reeves was born in upstate New York and his family moved to Colorado when he was four. He has always been hiker in the mountains; “(I) had a lot of experience out in the woods and understanding some things about being lost, that sort of thing,” he said.

After two tours in Vietnam, he returned to attend music school, was married and had four kids and then moved near Montrose, farmed and ranched for 12 years while a salesman for a feed company. After a divorce, he ended up in Grand Junction, back with a moving company he’d worked for in Boulder. He met his current wife, Mary while moving her to Salida as a new doctor in town.

In 1993, she gave him flying lessons as a present, and he started flying in 1994.

As a musician, choral director and new pilot, he met and became friends with the well-known and highly regarded Wil Atkinson, also a musician and the fixed-base operator at Harriet Alexander Airfield.

It was just happenstance that he climbed into Wil’s Cherokee Six on Feb. 8, 1995.

Reeves had planned to fly his wife to a medical conference in Boulder the next day, but at the airport it became apparent the weather would be turning bad and they cancelled the idea.

Atkinson was there with his plane for a charter flight to fly Johnson’s body to Cortez for relatives.

Reeves had only about 60 hours in the bigger plane, so Atkinson asked him if he would like to come along.

Their involvement in the murder case started earlier, and Reeves remembers the experience for a particular reason.

“Wil and I flew the plane to Denver and met the DA and his investigator after they had arrested the kid (Denison) and charged him, flew the DA and the investigator back to Salida,” he recalled.

“There was bad weather at the time, and Will didn’t file (a flight plan) and he ducked under the clouds on the way back to Salida and I was very uncomfortable … we would lose visibility now and then and kind of dive down a little bit and see and then find another valley … but it was a day when I started wondering about Wil’s choices. He taught me to fly so it’s a difficult thing, but I didn’t like the chances he was taking” he said.

On the day of their crash, the weather was changing.

“I looked out and the clouds were at 12-5 (12,500 feet) and I said to Wil, ‘how we gonna get over to the San Luis Valley?’”

They took off about two o’clock, with no way of knowing that in less than an hour, they’d be facing a life-and-death struggle.

“So Wil took off and was flying, he was having trouble climbing – it was a very interesting storm, it was going out of the Pacific and it was forecast to get pretty bad by Friday – this was Wednesday. So this was kind of a wind in front of the storm and it wasn’t turbulent, … it was just like downward pressure was pressuring what our engine thrust could do,” he said.

“And so he turned and headed down the valley toward Bighorn Sheep Canyon down the river and there’s a place right after you enter the canyon where the wind comes around the end of Methodist Mountain and drops down in and goes back up the other side, and you can almost always find lift over there. We went over there and the lift threw us upward into the air – we were going up oh, 1,500 to 2,000 feet a minute, which is a really heavy climb rate. And that should have been worthy of discussion between us, but we didn’t say anything.”

Things began to change not long after.

“At 15,000 feet we were on top and could clearly see our direction so he turned toward Hayden Pass and we kept going … we were probably at 17,000 almost 18, and he was starting to talk about whether he might file a flight plan.

“We headed toward the Sangres; we couldn’t see them, but we had kind of an idea where they were and as we got closer we entered into the downdraft – three thousand 300 feet a minute down and my ass started to pucker and as I watched the altimeter unwind past 15-5 (remembered), there were some 14,000-foot peaks just to the south of Hayden Pass, … and I’m getting nervous and thinking this is not a good plan and Wil says ‘maybe we should go back,’ and I said I agree, thinking he would turn toward Pueblo, and let down until we got below the clouds and then we could fly back under the clouds until we got back to Salida.”

The next moments would make all the difference. “But he didn’t do that, he turned right and back then there was a thing called a LORAN (a radio navigation system) he reset the LORAN for Salida and if you draw a line on a chart from where I think we were at that moment, back to Salida, it takes us kind of along the edge of the Sangre de Cristos.”

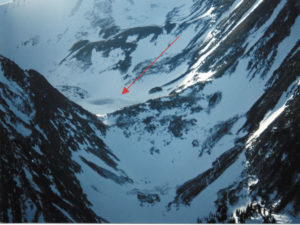

The downdraft pushed them down toward Stout Lakes. The lower of the two lakes is bowl-shaped, falling off steeply on one side where it ends in a waterfall, with boulder fields and talus slopes on the north side, near a meadow. The lake itself is quite deep. Fortunately, in February, it was frozen.

The downdraft pushed them down toward Stout Lakes. The lower of the two lakes is bowl-shaped, falling off steeply on one side where it ends in a waterfall, with boulder fields and talus slopes on the north side, near a meadow. The lake itself is quite deep. Fortunately, in February, it was frozen.

He describes the crash as happening in slow motion:

“And so the airplane slammed into that grassy knoll just in front of the lake in a nose-up attitude, coming down at a high rate of speed, but it ricocheted up into the air but that first impact drove the wheels into the wings and into the fuel tanks and emptied them, and it knocked the front wheel off there, the impact was so hard that the engine broke its top motor mounts and folded up under the airframe where we were sitting, and as we went up into the air it slammed down onto the ice with the left wing broken off, except for cables holding it and the right wing kinda bent up around the door.”

[InContentAd] That initial impact was just the start.

“So, now we’re going across the ice at about 60 miles an hour and we’re looking ahead through the windscreen at this rock cliff face that goes up to the next lake, looking like we’re going to hit head-on, with nothing left in front of us, and the left wing starts catching and jumping, and finally it spins and slams into the side of the fuselage on Wil’s side and breaks out the window and the wall and the panel underneath the window where all the switches were, rips everything and the wheel comes brushing by Wil’s face and slams into me, slams me into the side of the airplane and dislocates my right shoulder. But, as it lay against the airplane, the tail of the wing is dragging, and it caused the airplane to pivot around, changed its trajectory slightly, and we slam into the other side of the lake backwards, on the shore, just missing the rocky wall.”

Reeves asked Wil for help moving the wheel from his lap, which he couldn’t move due to his dislocated shoulder, but when he moved it and turned to go between the seats, “damned if it didn’t pop back in,” he remembers.

“We’re sitting there stunned and the first thing I remember is the wind blew into the open, broken side of the airplane and snow blew in on us.

“The only thing I could think of at that moment was ‘it’s 2:45 in the afternoon, nobody know where we are, it’ll be at least tomorrow before anybody comes looking for us, and I’m not getting any warmer than this.’”

Atkinson, described as slim, about six feet, two inches, was not dressed as warmly as Reeves, without even a hat. As they assessed their dilemma, Reeves remembers of his friend: “He didn’t seem … he was almost sometimes like he didn’t have the imagination to be afraid. It just seemed as if through this whole thing he was working with ‘what do I have to work with here and what should I do next’, and then he lost a lot of effort apologizing to me for what had happened and to the point that I finally said ‘Wil, I appreciate that, but I chose to get in the airplane, we’re here; none of this is going to get solved that way.’”

They went outside to inspect the plane. It was very cold at 12,000 feet with a strong wind blowing. The shivering in the partly open fuselage started soon after, described by Reeves as “a trembling, shaking, rattling of teeth that you have to clench your teeth to stop.” They huddled in the plane that night, using the sheepskin seat covers from the plane seats as skimpy protection.

After a frigid night, only dozing off and on, they decided the next morning to find their way down to the Arkansas River, anticipating that a search would be underway.

Snow was not that deep at the crash site, so they decided to take the seat covers and began to walk out.

Reeves said he was not in good physical shape then, and didn’t know about a trail near the lakes as they slowly tried to work their way down near a waterfall.

“Once we got down lower, we’d be walking and one would be breaking trail and one would be following,” he said.

The walking was very difficult, Reeves saw his friend was stumbling a bit and even he had to “post hole” and roll out of deep snow to stand up as they struggled along for hours.

Reeves remembers the point at which he saw Atkinson walking ahead, and suddenly noticed that when Wil picked up one of his feet, it was minus his shoe … a terrifying moment when he realized they were now in desperate circumstances.

He broke branch off a nearby tree and swept the area looking for the shoe, to no avail. After realizing how serious their situation now was, he encouraged Wil to put the seat cover over his foot and break trail in order to keep him ahead of Reeves, but Wil insisted he would follow as best he could.

“So I left; I started on down and when they found Wil … they said they thought he went over and sat down under a tree and that was it. They think he probably died within a couple hours of my leaving him.”

Reeves found it impossible not to get emotional and weep telling the story and the wrenching decision to leave his friend in order to seek help.

“I think that you don’t leave your buddy behind is the part of this that was so hard in telling the story and that was exacerbated by his wife, Joyce (and how she) reacted – she came by to see me to say she was glad I survived. I wanted to tell her what happened, and she didn’t want to hear it.”

As he was moving downhill, Reeves suddenly saw a helicopter off to the right in the canyon, fighting the wind to get in and search. He started waving the vest, and crying, knowing Wil was in trouble, but was not spotted. Unknown to him at the time, a search and rescue crew was readying to ride snowmobiles up the trail.

After the helicopter left, Reeves was having such trouble walking he decided to walk down the creek for easier movement, when he came to a drop-off and had to maneuver back to shore. As night approached, he came to a rock ledge with a dead tree over it and, cutting some branches for cover, crawled into the space out of the howling wind.

It was warm enough in the space that he noticed his blue jeans had thawed and he could drain his boots of water.

He got up to relieve himself, he remembers, and through tears, realized that he was perhaps going to survive. Under the moon there in the night he asked God aloud, “Okay God, I get it – I’m going to survive, going home tomorrow … I’ve got an hour left here until daylight, you want to tell me what you saved me for?”

He crawled back into his shelter and waited until daylight to begin struggling down once again.

Once walking, he found a trail of human footprints and began to wonder if perhaps Wil had come by him during the night, but realized there were more than one set of footprints, which probably belonged to searchers instead.

Because of his smooth-bottomed boots, his trail was indistinct, and he had not heard them calling in the night before.

He followed the searchers’ footprints until he came across the path left by their snowmobiles and then followed it.

After about an hour, he left the snowline onto dirt. He saw a Chinook helicopter searching, but again could not signal the pilot.

Undeterred, he continued following the trail he was on and then found a sign saying Stout Lakes, 3.45 miles (he realized he had come only about a mile and a half that second day after six hours of pushing through the snow). He then heard a noise and saw the searchers coming up out of the woods. One raced his snowmobile up to Reeves as he held onto the sign.

He asked, “What are you doing?” and Reeves responded, “I’m from the plane!” He was dehydrated, his throat so dry he could not even eat a snack bar, but gulped down some coffee.

He quickly gave precise directions to where he had last seen Wil and was taken to an ambulance south of Howard.

Rescuers were amazed, once they convinced him to take his boots off, that he had suffered no frostbite, a testament to his preparedness and courage. They walked Reeves’ trail back and found Atkinson’s body under a tree.

At the hospital, he was amazed at the number of people there who had been part of the search teams.

After an exam, he was released about one p.m., but only after a minister and his wife came in to tell him Wil had been located and had not survived.

“I had no frostbite, I lost nothing in that, I had a backache for six months,” he said, still amazed at his own survival.

“It was such an emotional moment for me.”

“It was pretty clear to me early on that the only way I was going to move on was to tell the story.” He has told it a lot of times, and works on telling it without as much emotion as he worked through for this telling.

After 18 years flying, he no longer takes to the air.

The body of Richard Johnson, whose murder linked the chain of events that led to the crash, remained in the plane because of snowstorms until a large helicopter could be flown in to recover the wreckage on Feb. 21. His body was taken to Blanding, Utah, shortly after for funeral services.

Print and broadcast journalist Dan Smith came to Salida few years ago to escape Denver, continue writing and slay trout.