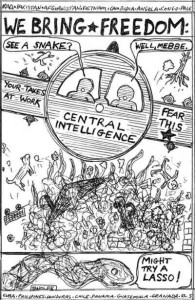

Article by Chas S. Clifton

Military History – March 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

In Tucson, Arizona, a home mechanic searches for an authentic replacement gauge for his M29 Weasel, a small, tracked cargo hauler from World War II, designed for traveling on the snow.

On Tennessee Pass, several generations of family, friends, and passers- by gather around a small group of elderly men in ski parkas.

On television, Rocky Mountain PBS adds a series on World War II to its play list of Antiques Roadshow, Lawrence Welk reruns, and talking heads.

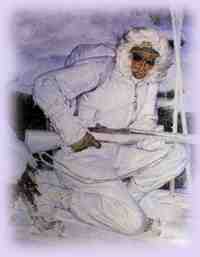

The University Press of Colorado (a collaborative effort of the state’s public universities) decorates its winter 2004 catalog with a photo of a ski trooper: baggy pants, white anorak, fully stuffed olive- drab rucksack, M- 1 Garand rifle.

One of the U.S. Mint’s five proposed designs for the Colorado commemorative quarter coin shows a ski trooper too.

In Toledo, Ohio, each new Jeep Liberty SUV is given an owner’s manual tucked inside an olive- drab canvas pouch that lacks only the “US” stamp and looks as though it could hold two 30- round magazines for an M- 1 carbine.

A tribute for the 10th

As the actual veterans fade away, World War II nostalgia stays with us — and one of its shrines remains Camp Hale, where the 10th Mountain Division trained from 1942- 44. For an extra $25, Coloradans can buy 10th Mountain Division commemorative license plates. We can drive on the 10th Mountain Division Memorial Highway (U.S. 24 over Tennessee Pass), and we can consume a still- increasing number of books and documentaries about the unit.

On a Saturday last winter, the actual veterans and the nostalgia brigade came together on Tennessee Pass. Some of the ex- ski troopers (all at least 80 by now) had spent the day skiing, some with faded divisional insignia sewn to the latest synthetic ski parkas. It was their annual reunion, part fun and part memorial for the events of “60 years ago last weekend,” when the mountain infantry and supporting units of the 10th were thrown against entrenched German forces on the Gothic Line, a series of defensive positions stretched across mountainous northern Italy.

With the veterans, and their friends and family was another group: the attendees of “Operation Blizzard 2005,” collectors of Weasels, the name given to a series of small tracked vehicles built for the war effort and the ancestors of Sno- Cats and similar vehicles today.

With the Weasel owners, camped in military- surplus pyramidal canvas tents along the flats of the Eagle River where once stood Camp Hale was another group of ski- trooper re- enactors, accurate to the last buckle and the swagger in their step. While the 10th’s chaplain offered an invocation, and another veteran read a poem about the men who have come home again to where they “trained in winter’s frigid gales,” the re- enactors skied Chicago Ridge above Ski Cooper for the benefit of a documentary film crew.

Undoubtedly, each member of each group would call his contribution a tribute to the original soldiers of the 10th.

Where do you put ski troops?

For Colorado, the 10th Mountain Division turned out to be more than a military unit. It was a cultural force. Veterans of the 10th changed American sport, fired up the environmental movement, and for better or worse, turned Colorado into “Ski Country USA.”

Its initial history, however, was full of contradictions. The division, built around three mountain- infantry regiments, the 85th , 86th, and 87th, was hyped by writers and movie makers before it even fired a shot in combat. But once it was in place, the Army brass did not know where to put it. When elements of the division first saw combat (in the Aleutian Islands), all their casualties came from friendly fire.

A misconception about German strategy helped drive the division’s formation. In the Winter War of 1939- 40, an outnumbered Finnish army repelled invading Russians with their superior ability at winter fighting. Not only did the Finns have ski troops, they even resorted to hit- and- run attacks involving a rapid withdrawal on frozen rivers using ice skates. But in the end, the Red Army’s numbers counted for more, forcing Finland into an uneasy alliance with Nazi Germany.

Meanwhile, German blitzkrieg (“lightning war”) victories against Poland and France put some Americans’ nerves on edge. Distressed by German submarine attacks on Atlantic shipping and by news reports hyping the danger of German spies, Americans began to fantasize about a transatlantic invasion, with the German army landing in Maritime Canada and then striking down the old invasion route of the French and Indian War — Lake Champlain and the Hudson River. Where were America’s Winter Warriors?

In fact, Germany had no territorial designs on Canada and the United States. What Hitler really wanted was the fertile farmland of Poland, Belarus, Ukraine, and western Russia, plus the oil fields farther south.

Nevertheless, one of those concerned Americans, Charles Minot “Minnie” Dole , insurance executive, skier, and founder of the National Ski Patrol, refused to let go of the issue. (He was not related to former Kansas Sen. Bob Dole, who may be the best- known 10th Mountain veteran.)

Minnie Dole and his friends lobbied the War Department constantly with this refrain: America needed cold- weather soldiers — ski troopers and mountaineers. Considering that the US Army was more used to Western prairies and deserts, to the tropical environs of Cuba and the Philippines, and even to the temperate climate of France during World War I, theirs was a novel concept.

But thanks to Dole and his fellow Ski Patrollers, the Army reluctantly agreed to the formation of its first six “ski patrols,” attached to different divisions. Reports of the fighting between Italian and Greek units in the mountains of Greece and Albania helped Dole’s case. In late 1941, the 87th Mountain Infantry Regiment was organized at Fort Lewis, Washington, and trained at National Park Service lodges on Mount Rainier.

The news media noticed. The 87th included not just Americans — it attracted volunteers who already knew how to ski, still an elite activity in 1930s America — and it also attracted Europeans, including some big name racers and ski- jumpers, primarily Austrians and Norwegians whose homelands had been overrun by Germany.

Meanwhile, even as the mountain troops swapped rumors about a possible attack into Norway, the automaker Studebaker was tasked with developing a tracked vehicle small enough to be air- dropped as part of a commando mission in that very country. Some soldiers from the 87th were sent to the Columbia Ice Fields in Canada to help test the “Weasel,” which was developed in slightly more than a month in mid- 1942. The Norway operation never happened, but the 10th Mountain Division and other units did make use of Weasels elsewhere.

In late 1942, the 87th was moved to a new training camp high up on the Eagle River at the Pando rail siding — Camp Hale, which grew to house thousands of men, plus some German prisoners of war captured in North Africa.

In the meantime, the actor Alan Ladd was appearing as a “recruit” in a new ski movie, The Basic Principles of Skiing, with other roles filled by ski troopers. It was filmed at Sun Valley, Idaho, but Warner Brothers’ 1943 film Mountain Fighters was shot at Camp Hale. And the 1944 movie I Love a Soldier, featuring Paulette Goddard and Sonny Tufts, meant that ski troopers were loaned to Paramount studios.

National Ski Patrol men were given short movies featuring the 10th to show to ski clubs as a recruiting tool. In all, says writer Peter Shelton, about half of the 10th’s 14,000 men were skier volunteers while the others arrived through the mysterious ways of the Army; and some of the latter were not happy to be put on skis at all.

The 10th’s first combat came in one of the war’s less- known theatres, the Aleutian Islands, where the Japanese had occupied some of the farthest- out pieces of the island chain. Soldiers from the 7th Infantry Division had fought a vicious battled on Attu in May 1943. In July, the 87th regiment was sent to another island, Kiska, together with other American and Canadian units. Unknown to them, the Japanese had evacuated the mountainous island. Inexperienced and confused in the fog, wind, and horizontal rain, units blundered into each other and fired, costing the regiment 17 dead and more wounded. Others were killed by Japanese mines and booby- traps.

In most operations, the Army had no use for mountain infantry. They were not called for the 1942 Operation Torch landing in North Africa, nor for the subsequent invasions of Sicily and southern Italy. In the spring of 1944, at peak strength, the division’s soldiers went through high- altitude war games in the midst of a spring blizzard — and then, the same week as the D- Day invasion of Normandy, the Army sent the 10th to southern Texas to be reorganized as a more typical heavy infantry division. Dole and his allies, however, pleaded for a combat assignment for the 10th.

Finally, in late November, the 10th was sent to Italy, where the slow slog up the “boot” had been overshadowed by the Normandy landings in June. Here there were mountains, and the 10th was given the job of capturing key ridges that controlled the highway north from Florence to Bologna. The Germans met them with propaganda leaflets fired in artillery shells: “Welcome, men of the 10th Mountain Division. It’s a long way from Camp Hale to Mount Belvedere.” The enemy was fully aware of the 10th’s movie roles, its magazine covers, and its flattering news coverage back in the States.

Most of the division’s technical climbing gear stayed home, as did its pack mules, although some Italian mules were used to carry supplies and the division’s mountain howitzers. A few patrols went out on skis before the weather warmed. Captain David Brower (later better known for heading the Sierra Club and Friends of the Earth) wrote that by the time the division was actually in the mountains, “the equipment and clothing with us was no different from the ordinary flatland GI’s, right down to the last shred of underwear.”

The mountain soldiers were given difficult assignments, capturing “unassailable” German positions that included climbing high ridges and fighting through a series of highway tunnels against dug- in enemies. Casualties were high, with more than a third of the division killed or wounded. Yet one German general, Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin, rated the 10th as “my most dangerous opponent,” and when German forces in Italy surrendered, von Senger made a point of surrendering to a detachment from the 10th.

In the lull that followed the German surrender in May 1945, many of the 10th’s mountaineers probably agreed with E.P. Motley, a Harvard student who had joined the 10th in 1944: “I believe that some of us, myself included, hated combat, but were also discontented with the prospect of lives free of risk and thrill.”

Motley, who had been wounded once, proceeded to break his leg while teaching a rock- climbing class when one of his students fell and took his instructor with him. Other soldiers took captured German skis and skied as much as they could in the high snowfields of spring, while others hurled themselves at Alpine peaks that they had only read about. It was a happy summer until they were reassembled for the planned invasion of Japan; then the atom bomb negated that operation.

They just wanted to teach people to ski

The military epic was over; now the capitalist epic began. Émigré Austrian skier and 10th veteran Friedl Pfeifer enlisted industrialist Walter Paepcke and his wife Elizabeth in a plan to turn the decayed mining town of Aspen into a ski center. Minnie Dole was an investor, along with the Secretary of Navy (Elizabeth Paepcke’s brother) and other veterans of the 10th. In Peter Shelton’s words, “The energy that 10th vets brought to the ski business — as coaches, racers, ski instructors and patrollers, ski school directors, filmmakers, shop owners, publishers, writers, and equipment manufacturers and importers, as well as ski- area developers — would have been difficult to replicate.”

Veterans developed or had a hand in developing ski areas from Aspen, Buttermilk, Vail, and Arapahoe Basin in Colorado to others in Oregon, Washington, New Mexico, Vermont, New York, Massachusetts, and Pennsylvania.

As it turned out, a ski trooper didn’t make it onto Colorado’s commemorative quarter. But perhaps one really belonged there, although, to be fair, there should have been a golf course, gondola lift, hotels and condominiums below him.

And if not all of the mountain terrain featured on the coin has been built on, we might do well to reflect on the influence of David Brower, first executive director of the Sierra Club, and Paul Petzoldt, who founded the National Outdoor Leadership School at the foot of the Grand Tetons — former ski troopers both.

If the coin had ended up in our pockets, the soldier’s image would have carried multiple messages — true valor in a war that had wide public support, and the postwar expansion of skiing, climbing, and backpacking — along with all of the problems and rewards that arose when skiing became a main prop for the mountain counties’ economy.

But Gov. Bill Owens picked a different design last year, a generic mountain ridge. Coin or no coin, though, the 10th Mountain Division will be remembered.

Chas Clifton lives in Wetmore and teaches English at Colorado State University, Pueblo.