by Colorado Central Staff

The year was 1895 and the city of Leadville had fallen on hard times. Since 1881, production had declined at its largest and most profitable mines. The repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act in 1893, first enacted to increase the amount of silver the government was required to purchase every month, had a crippling effect on the local economy. By 1895 the population had dwindled to 14,477 residents from nearly 40,000 only two years previous.

The city was desperate. “Ruin and bankruptcy stared every mining man, every smelting man, and every businessman in the face,” reported the Herald Democrat.

Then a group of community members led by an English-born developer, Edwin W. Senior, had an idea: what about a major tourist attraction, one that would bring visitors and money flocking to Leadville? Thus was born the idea of a grand Ice Palace, complete with a carnival, exhibitions, a restaurant, ballroom and skating rink – all constructed from blocks of ice. Senior previously organized train excursions that took prospective Leadville buyers to visit his Salt Lake City developments, and sent trainloads of spring flowers to be given away to Leadville citizens before their own spring flowers bloomed.

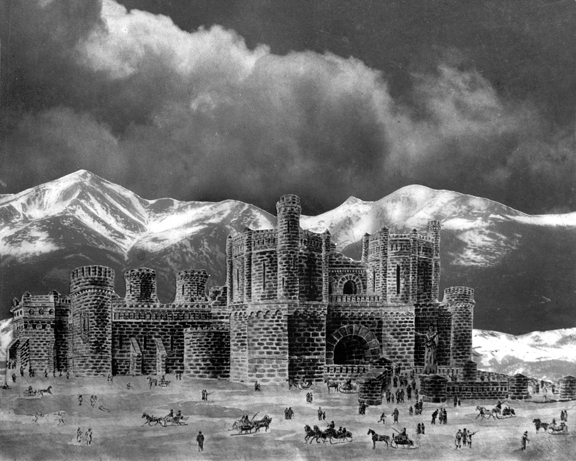

The idea caught on and organizers began their ambitious project by hiring an architect, Charles E. Jay, whose resume included an ice castle in St. Paul, Minnesota designed for its Saint Paul Winter Carnival in 1886. But Leadville had even grander ideas for their ice palace–it would be a permanent structure–used for carnivals and events in the winter and a public meeting hall in summer. It was decided the palace would be built on top of Capitol Hill, between Seventh and Eighth Streets, where it would dominate the cityscape.

Senior resigned from the project after helping raise only $4,000 of the $12,000 estimated cost of the ambitious scheme. The word was that he didn’t like soliciting contributions from saloon and brothel owners, because he didn’t personally approve of their businesses. And they understandably weren’t enthused about contributing to someone who disapproved of them. That was a big problem, as taking saloons and brothels out of the mining camp contributor mix didn’t leave a lot. So the other Ice Palace organizers pressured him to resign his leadership position, and he agreed to do so. The project was then taken over by Tingley S. Wood, a local businessman who offered to match any funds raised by the citizens of Leadville. For $1, locals could purchase stocks in the project. By Christmas Day, 1895, more than $40,000 was raised but estimated construction costs had risen as well, still leaving a shortfall of nearly $20,000.

But enough money had been raised for the construction to begin by November 1, 1895. The structure was not actually built of ice, though, the ice blocks were for appearance only. The Palace was actually supported by a framework of girders, trusses and timber. 5,000 tons of ice were required for the walls, much of which was hauled in from Palmer Lake, between Denver and Colorado Springs, 75 miles away, after being hand-sawed into blocks and loaded onto sleds. Upon arrival at the construction site, the ice was trimmed and placed into forms. It was then sprayed with boiling water which helped to bind the 22-inch thick blocks together.

A crew of 250 men worked around the clock to construct the 58,000 square-foot palace. A late-November scare, when temperatures rose to the unseasonal 60s, forced Wood, the principal investor, to shell out an additional $5,000 for enough canvas to cover the half-completed structure and avert a meltdown.

On January 1, 1896, after much publicity and promotion, the Leadville Ice Palace had its big grand opening. More than 2,000 visitors arrived to marvel at the five-acre palace with its 90-foot high octagonal ice towers complete with turrets, a 20-foot wide promenade, electric lights frozen within the ice blocks, prismatic search lights and 190-by 80-foot skating rink. A parade was held to celebrate the opening which featured the 2,000 member Miners Union, local dignitaries, the hockey club, firemen and other notables with an array of local citizens bringing up the rear.

Opening day entertainment was provided by the famous Dodge City Cowboy Band of Kansas. Parade Grand Marshall W. R. Harp took the first icy plunge down the toboggan run as part of the festival’s initiation. Later that evening a grand lighting ceremony was held, and thousands braved 22-degree temperatures to witness the spectacular lighting of the Ice Palace.

Admission to the Palace was 50 cents for adults and 25 cents for children, which included use of the ballroom and skating rink. Season tickets were also available for repeat visitors. As a clever method of product display the restaurant had embedded food within the ice blocks. Red roses, even trout, were frozen within the clear ice blocks on the interior walls for visitors to gaze upon.

Welcoming attendees at the main entrance was “Lady Leadville,” a 19-foot tall ice sculpture on a 12-foot ice pedestal – her right arm pointed to the once-prosperous mines to the east of town. Above her left arm was a scroll embossed with the figure $200,000,000 in raised gold figures, representing the revenues produced by the mines of the Carbonate Camp.

Independent vendors set up shop adjacent to the Ice Palace hoping to cash in on the attraction, including a Merry-Go-Round and the Palace of Living Arts and Illusions which featured poetry, theater and macabre illusions.

Locals were encouraged to get into the carnival spirit by decorating their homes and businesses as well as themselves by dressing in brightly colored festival costumes.

At the time there were three railroads servicing Leadville, and the hope was that the winter season would bring record numbers of spectators to the Ice Palace and help get the local economy back on its feet. The railroads did their part to promote the attraction by offering special round trip rates, adding extra cars, and printing and distributing advertising posters. Reservations came from across the country and the railroads jostled for positions to provide special accommodations and excursions.

But things didn’t work out quite as the city had hoped. Within days of the palace’s opening, rumors began circulating in Denver newspapers of problems in Leadville such as the palace ice melting and falling walls. The papers also warned of limited food availability and supposed thievery in the town, neither of which was true. The Leadville Herald Democrat had to assure readers these rumors were false and without merit. Many visitors only came for the day, packing their own lunch, to the dismay of restaurant and hotel owners.

[InContentAdTwo]

To maintain outside interest in the festival, organizers began featuring events and competitions such as speed-skating and hockey. The State Skating Championship Men’s Race was held at the palace that winter, and statewide dignitaries and newsmen were wined and dined after the event in hope of generating additional publicity.

Fancy dress contests and a “Best Impersonation of President Grover Cleveland” competition required doling out prize money which had to be drawn from ticket receipts. Special days were held including Wheelman’s Day (for bicyclists), Stock Exchange Day – in which seats on the exchange were offered for sale – Colorado Press Day, Shriner’s Day, Irish Day, Western Slope Day (in conjunction with America Day and Salida Day) and Aspen Day, for residents of that prosperous mining community to the west. Even “Colored People” were recognized on February 24.

But as fate would have it, March of 1896 brought unseasonably warm temperatures and lower attendance figures. The Palace actually began to melt as snow began receding from the mountainsides, and on March 28 the last official ceremony of the Winter Carnival was held.

Cost overruns in the construction, the high cost of the prizes awarded and visitor expenses added up to a substantial loss for the investors, who had no appetite to repeat the gamble again.

The ice rink continued to be used until late May but, because of the continued depressed economy and a looming miner’s strike, the construction lumber was dismantled and resold. Some of the lumber was used for flooring in barracks erected for state militiamen who were brought in to quell the violence and rioting that were the result of the miners strike. While the strike was preoccupying the citizens of Leadville, the remainder of the Palace was demolished in October of 1896 and hopes for an annual carnival melted away as well.

Almost one hundred years later, in 1985, the city did a cost study on building another ice palace but estimates came in around $30 million, quickly putting that idea to rest. The city again considered building another ice castle at about one-quarter the size of the original, on the centennial of the original festival in 1996, but organizers fell short of the $1-million that would have been required and the idea dissolved.

Today, Ice Palace Park in the 100 block of West Tenth St. commemorates the Ice Palace, and Crystal Carnival weekend is held every March in Leadville with events and a parade.

References:

Weir, Darlene Godat: Leadville’s Ice Palace, A Colossus in the Colorado Rockies. Ice Castle Productions, 1994.

La Rocca, Lynda: The Leadville Ice Palace, a tourist attraction that melted. Colorado Central Magazine, March 1994.

Garner, Joe: Ice Palace capped riotous era. The Rocky Mountain News, May 1999.