Part 3: The Fry-Ark Project

By George Sibley

In 1948, after six years of study and planning, it finally happened: the Bureau of Reclamation released plans for a big project to bring water from the Gunnison River Basin through Central Colorado to the Arkansas River Basin. A really big project – exceeding the fondest dreams of Arkansas Basin water users – the “Gunnison-Arkansas Project” proposed transferring 600,000 acre-feet of water through the Continental Divide. That was twice as big as the Colorado-Big Thompson Project up north, moving West Slope water to the South Platte Basin.

Unfortunately for the Arkansas Basin, the project as proposed also exceeded the resources of even the federal government for bringing it about. It also probably exceeded the natural resources of the Gunnison River Basin, and other watersheds into which the project would have extended.

The Bureau’s Gunnison-Arkansas Project was to be built in two phases. Phase 1, the “Initial Development,” would be a diversion of around 70,000 acre-feet a year from the Fryingpan and Roaring Fork River headwaters, tributary to the upper Colorado River. The Bureau wanted to start building the “Initial Development” as soon as possible.

Phase 2, titled the “Maximum Gravity Diversion,” was a literal pipe dream of stupendous scope. It was proposed to collect water from all the Upper Gunnison River headwaters tributaries through collection ditches, accumulating that water in a new reservoir near Almont, above Gunnison. It would also bring to that reservoir, via more collection ditches, conduits and tunnels, water from the Anthracite Creek watershed in the North Fork of the Gunnison, and from the Crystal River in the Roaring Fork watershed. From the Almont reservoir, the water would be pumped uphill to a reservoir in Taylor Park, and from there taken through a tunnel under the Continental Divide into the Arkansas Basin.

The waters from both Phase 1 and 2 would emerge on the East Slope for storage and controlled release in a number of comparatively small reservoirs in the Arkansas Basin above Salida, and a large 350,000 acre-foot reservoir above Pueblo. Electric power would be generated at several East Slope dams and other drops, to help repay the pumping costs on the West Slope – it was by no means all gravity.

The people of the Gunnison Basin, all the way down to the “Grand Junction” with the Colorado River, were, as always, vigorously and noisily opposed to this plan – and not without justification. The Bureau’s Uncompahgre Valley Project and a private Redlands Power and Irrigation system near Grand Junction had very large, very senior water rights on the Gunnison. The people believed that a project that wanted to remove half a million acre-feet of what was left essentially precluded future water-based development in the Gunnison Basin.

By 1950, however, the big Maximum Gravity Diversion simply disappeared from all discussion of the project. This was probably at least partially due to the huge – almost unimaginable – cost of the plumbing involved in collecting and moving that much water over great distances. But it was probably more due to the fact that, in the Bureau of Reclamation, the right hand did not always know what the left was doing. The Gunnison-Arkansas Project had come out of Bureau Region 7, the Great Plains office. But Bureau Region 4, the Upper Colorado River office, was also making plans for its even larger Colorado River Storage Project, and politically that took precedence on the West Slope over the Great Plains Region’s plan.

After 1950, the Gunnison-Arkansas Project “Initial Development” came to be known as the “Fryingpan-Arkansas Project.” Thus, did the hopes of the Arkansas basin irrigators and urban movers and shakers get diminished by 90 percent, although down to the present strong spirits like Bob Rawlings of the Pueblo Chieftain and former State Engineer Jeris Danielson of Southeastern Colorado have never given up on the idea that, someday, there will be Gunnison Basin water for the Arkansas River.

But 70,000 acre-feet of water every year would be better than nothing, and the Arkansas Basin people got behind that idea and pushed, as did their Congressman Edgar Chenowith. But through the early 1950s, they found their dreams competing with the Colorado River Storage Project, and with the man who would give them fits for another decade, Colorado’s West Slope Congressman, Wayne Aspinall.

Even as early as 1950, his second term, West Slope Coloradans saw in Wayne Aspinall the reincarnation of Congressman Ed Taylor. Also a Democrat thriving in the mostly agrarian-conservative West Slope, Aspinall reforged Taylor’s coalition of moderates from both parties and remained in office for 24 years, until the political upheavals of the early 1970s.

He chose the House Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs as a strategic spot to build a power base, and within a decade of his 1948 election was chairman of that committee, running it with an iron hand based on a thorough knowledge of the House’s complex rules of governance.

From the start the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project was problematic for Aspinall. His passion during the early 1950s was the Colorado River Storage Project, whereby the waters of the Upper Colorado River Basin would be developed for use in the four states of the Upper Colorado River Basin: Colorado, Utah, New Mexico, and Wyoming. In the late 1940s, those states had finally gotten around to negotiating a compact for allocating the Upper Basin’s share of the river, under the 1922 Colorado River Compact.

Neither compact prohibited diversions out of the natural basin – Utah and New Mexico, in fact, planned on trans-basin diversions from the start (the Central Utah Project and the San Juan-Chama Project). Aspinall, however, wanted Colorado’s share of the river (51.75 percent of the Upper Basin share) to take care of Colorado’s West Slope and the downriver obligation to the “desert states” first, and the Bureau of Reclamation plan for the Colorado River Storage Project reflected that desire. CRSP, as it was finally passed, would consist of three big storage dams and reservoirs with big hydroelectric generating capacities: Flaming Gorge on the Green River, the three-dam Curecanti Unit (now the “Aspinall Unit”) on the Gunnison River, and the huge Glen Canyon Dam and Reservoir below the junction of the Colorado and Green Rivers. In addition to storing over 30 million acre-feet of water, these would be “cash register dams” for generating power revenue to pay back not only their own cost, but ultimately the cost of 20-some smaller projects for irrigation and municipal-industrial uses that could not otherwise meet cost-benefit criteria.

The Fry-Ark Project (as it came to be called) was a dilemma for Aspinall. As a West Slope Congressman in his first two or three terms, it would have been political suicide at home to have actively advocated for a trans-Divide diversion. But if he wanted the rest of the Colorado congressional delegation to support “his” Colorado River Storage Project, then he had to at least appear to bless the Fry-Ark.

The Fry-Ark Project did not make it out of the various committees to vote of Congress until 1953; the more collegial Senate passed it, but the House voted it down. It made it to the floor again in 1955, and was again voted down. Aspinall voted for the bill each time, which displeased the people of the West Slope – but he also displeased the rest of the Colorado delegation and the people of the Arkansas Basin by not speaking out in favor of it to the rest of the House.

After the 1955 Fry-Ark defeat – a difficult time for the Storage Project idea too – Aspinall stated that, so far as he was concerned, the Fry-Ark Project would have to wait until the Storage Project Act passed, assuring sufficient storage on the West Slope to be able to spare the water for the East Slope. After the Storage Project Act passed, he promised (when away from the West Slope) that he would give the Fry-Ark Project his full attention.

The people of the Arkansas Basin, meanwhile, became much more proactive about the project. In 1954, led by Charles Boustead, they began the petitioning process to create the Southeastern Colorado Water Conservation District to coordinate planning with the Bureau of Reclamation and to send lobbyists to Washington to push the project. To raise money for that effort, the “Golden Fryingpan” was created: little ones for five dollars, big ones for one hundred.

The Storage Project finally squeaked through Congress in 1956, after compromises with an environmental movement that was growing in strength and coherence. Laying the groundwork for new projects gave the people of the West Slope plenty to think about and work on. Aspinall was able to work more aggressively for the Fry-Ark among his colleagues in Congress – he had to, in fact, if he wanted the rest of the Colorado delegation to help keep a stream of funding flowing for the Storage Project units, large and small.

Keeping such funds flowing was growing more difficult. On the national level, a largely urbanized and industrialized nation was losing interest in the agrarian-utilitarian reclamation project it had embraced at the turn of the century. National sentiment was shifting toward the idea that any remaining free-flowing rivers should be left that way for the enjoyment of the people, rather than dammed, diverted and put to work for the people. This was even becoming an issue on the West Slope, where a pro-reclamation plank was still necessary on a political platform, regardless of party.

For his second term, beginning in 1957, President Eisenhower declared that he would approve no new reclamation start-ups beyond the billion-dollar Storage Project, so the Fry-Ark Project went dormant again for a few years – although the faithful kept selling Golden Fryingpans in the Arkansas Basin.

Things changed again with the election of John F. Kennedy. He and his Interior Secretary Stewart Udall developed a complex western-states public land policy that sought a significant increase in land protected for the enjoyment of the people rather than opened up for development. But that was balanced by a commitment to carrying forward the national reclamation project: more dams on the rivers, more water moved out of the rivers for human uses – while simultaneously advocating for more water-based recreational opportunities. Much of the apparent contradiction there is explained by the presence of Wayne Aspinall as chair of the House Interior Committee. He was a savvy fox who knew how to keep a bill away from a House vote forever if it did not fit his vision for the full utilization of the resource base of the interior West. And, Aspinall was enough of a horsetrader himself to know that, for example, he was going to have to acquiesce to some kind of a Wilderness Act and protection for “wild and scenic rivers” if he wanted to see the water projects continue elsewhere on western rivers.

The Fry-Ark Project came back to life at that point, despite its unfortunate history as a two-time loser, and the fact that the Bureau’s cost estimates had passed $150 million for a relatively modest amount of water moved. Aspinall promised to get it passed during the 87th Congress (1961 and 1962 sessions). But there were, of course, frustrating problems and delays.

The Fry-Ark Project got entangled with a Colorado River Storage Project unit in New Mexico, diverting water from the San Juan River Basin into the Rio Grande Basin. New Mexico Senator Clinton Anderson was chair of the Senate Interior Committee, and could move or hold up the Fry-Ark Project bill, just as Aspinall could move or hold up the San Juan-Chama Project bill.

But rather than just rolling each other’s logs, Aspinall found a problem with Anderson’s strategy for passing his San Juan-Chama bill. Anderson had bound the SJ-C bill together with a Navajo Indian Irrigation Project bill, figuring that sympathy for the Indians would help his bill pass. But Aspinall did not want to let the Navajo project out of committee unless the Navajo nation agreed to surrender its “federal reserved rights.” To reduce the books that have been written about “federal reserved rights” to a sentence: the U.S. Supreme Court had declared (in a 1908 case involving a Montana Indian nation) that whenever the federal government “reserved” public lands for any purpose (Indian reservation, national park, national forest), it also implicitly reserved enough water to carry out that purpose, and could file claim on that much water whenever it got around to it. This planted legal time bombs when it made land reservations in the West, which was just about everywhere. For a reservation the size of the Navajo nation’s, the entire Colorado River could have been sucked up in reserved rights.

The Navajo nation eventually, reluctantly, agreed to surrender its future reserved rights in order to get its irrigation project through Aspinall’s House committee. But by then, both Anderson and Aspinall agreed that it was too late in the Congressional year to get their respective bills passed, so they were held over to 1962.

The people of the Arkansas Valley kept selling Golden Fryingpans.

Finally, without further problems beyond the grumbling of eastern Congressmen at the probable costs of the projects, both of Anderson’s two projects and the Fry-Ark Project were shepherded through Congress. On August 16, 1962, President Kennedy himself flew to Pueblo to sign the bill and announce to a cheering crowd the authorization of the Fryingpan-Arkansas Project, the occasion for celebration this year in the Arkansas Valley on its 50th anniversary.

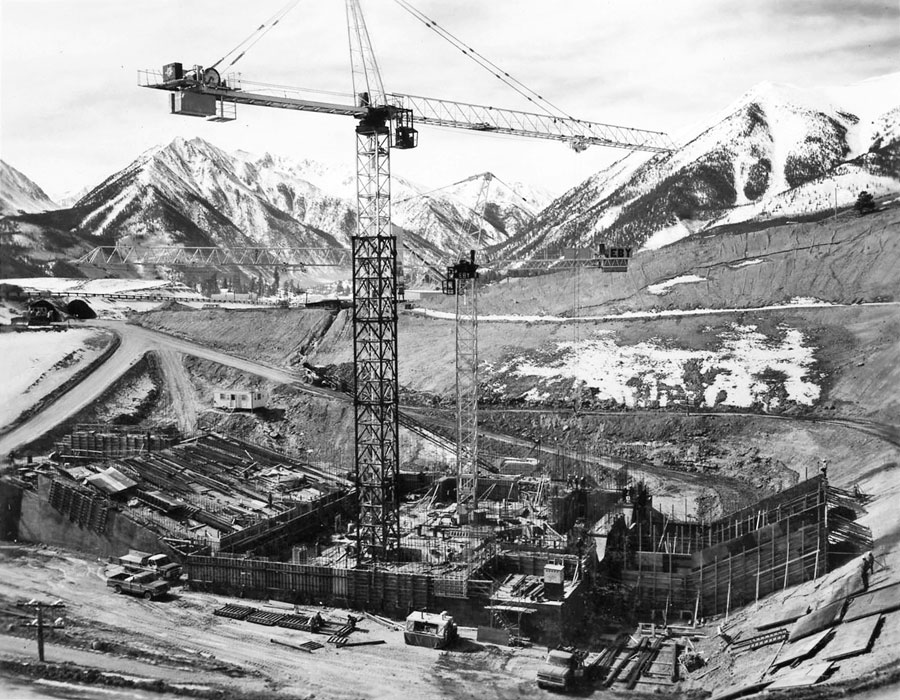

Construction on the West Slope Fryingpan River collection facilities and the tunnel under the Divide (later named after Charles Boustead) began in 1964 – along with a “compensatory storage” dam and reservoir for West Slope use, Ruedi Reservoir, farther down on the Fryingpan River. How that came to be is a story in itself, but one not that relevant to Central Colorado.

The Bureau estimated in 1964 that the project would take around 13 years, and cost not more than $170 million. It ended up taking almost 20 years to complete, and costing more than $500 million. During that time – and accounting for some of the additional expense – the nation moved conclusively into the “environmental era,” and many aspects of the Fry-Ark Project had to go through the additional cost and delay of Environmental Impact Statements under the National Environmental Policy Act. Colorado also adopted an Instream Flow Act that complicated the Bureau’s slightly slapdash way of computing “fish flows” for West Slope collectors.

But by the mid-1970s water was finally flowing from the West Slope into the Arkansas River, a long-time dream for Arkansas Valley irrigators and other water users. When completed, the project consisted of six storage dams (all but Ruedi on the East Slope), 16 diversion structures intercepting creeks on the West Slope, 4.3 miles of canals, 282 miles of conduits, 27 miles of tunnels, two powerplants (instead of six originally planned), 12 miles of transmission lines, two switchyards, and two substations. The Pueblo Dam, the so-called “crown jewel” of the project, is a unique structure, an earthfill dam fronted by massive concrete buttresses.

The Arkansas River, top to bottom in Colorado, is now essentially a waterworks that runs primarily at the will of its many users, from the Upper Arkansas rafting industry to the irrigators down at the Kansas border, and most of the municipalities in between. It conveys West Slope water to a pumping station that moves it under Trout Creek Pass to the South Platte Basin; the waterworks will soon be extended north from Pueblo Reservoir to Colorado Springs – a major uphill run via the Southern Delivery System.

Amazingly, all of this reconstruction of the river is relatively low key on the landscape. It remains a beautiful waterway in a spectacular environment, a central attribute of Central Colorado. Now if only it had just a little more water …