By Hal Walter

It’s never easy to say goodbye to a close friend but when Curtis Imrie headed over the pass last month, I found myself scrambling for words and trying to regain my own sense of balance and direction.

My first reaction was, Curtis can’t die. For here was a man who lived life by his own rules. Then again, how better to exit this life than to go while doing something you love, in this case showing donkeys at the National Western Stock Show.

My friend Miles F. Porter IV introduced me to Curtis in 1980 when I ran my first marathon in Denver. Later that summer we visited Curtis’ cabin at 4 Elk near Buena Vista and Curtis convinced me to give pack-burro racing a try. We became fast buddies. Curtis was initially the crazy brother-from-another-mother that every young man should have. Later in life he would evolve into a mentor of sorts. After his passing I realized he was a once-in-a-lifetime friend.

In the early days hanging out in Curtis’ “Lost Frontier” we pushed the envelope training burros. I recall entire days running on the trails in the mountains surrounding Buena Vista, returning to the ranch after sunset exhausted, riding the burros bareback homeward in the dark the last few miles. When we were not training we talked about writing, and he introduced me to great authors like Jim Harrison, Edward Abbey and Thomas McGuane.

The yearning for adventure ran deeply through Curtis’ soul. In those early days we spent a considerable amount time and effort on a futile treasure hunt. A pilot had walked away from a winter plane crash near Kroenke Lake in the Collegiate Range and his body had not been recovered. Rumor was the family was offering a sizable reward for finding his remains. We never did find the body but I still have some great memories of exploring the high tundra and boulder fields in the shadow of Mount Yale with Curtis and the burros.

This was just the beginning of a long chain of stories that could fill a book, and that nobody would even believe unless the central character just happened to be Curtis.

To be clear, Curtis was no deity, small or large. He had faults and his own dark side just like the rest of us. He broke lovers’ hearts. He pissed people off over minor infractions. He made people cry for reasons that seem silly now. Yet this does not mean he did not possess a heart of solid gold.

Many people know the outward Curtis who was a champion pack-burro racer, independent filmmaker and actor, rancher, political candidate and radio show host. Many do not know the side that seemed to take underdogs he encountered in life under his wing, perhaps because he was one himself. He may have done this with me – in fact every burro I ever won a race with came out of Curtis’ program, and one of my books, Full Tilt Boogie, was inspired by his urging me to write about the cards I’d been dealt as the father of an autistic son.

In fact, Curtis was the quiet champion of many people who are different and those who face mental-emotional, physical, intellectual and other challenges. This list would be too lengthy and personal to publish. But one of these underdogs was my son, Harrison.

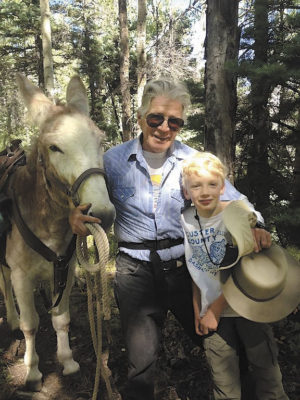

Since Harrison was very young, Curtis had always been part of the fabric of life around here. “Uncle Curtis” was part of the family and an early influence on Harrison. Harrison knew him from the burro races early on, and Curtis often visited during his ramblings about the countryside on political crusades or moving burros back and forth between his ranch and mine. Their play “wrestling” would spark shouts of “Let’s take it outside!” whenever Harrison saw him. Curtis had established a campsite at my house and would often pull in with his truck and camper on short notice to spend the night before moving on the next day after coffee.

When you have a child on the autism spectrum you tend to examine your own quirks and also those of your close friends. At some point in time I began to wonder if Curtis might be on the spectrum himself. Regardless, he certainly had a way connecting with Harrison on his own level, and the support he provided me through all of the challenges we’ve faced with Harrison is irreplaceable. In recent years much of my conversation with Curtis had focused on these challenges, and when Harrison melted down terribly at a track meet in Salida last spring, Curtis was one of the friends who helped me escort him out of the tense situation.

One of the more heart-wrenching components of Curtis’ passing has been Harrison’s reaction to his death. His initial impulse was loud and violent. He ran at me swinging his arms and screaming, “No! No! Curtis has not died!’” During this moment I was still processing Curtis’ death myself and Harrison’s outburst was almost more than I could bear. The only thing I could think to do was to hug him tightly.

The emotional pain of this experience was so intense that I actually blacked out. I found myself in a dark space I have never experienced before. It seemed like a room with a tunnel on the other side. It was inky black like water on a moonless night, and infinite. I felt I was being given the choice to travel forward into this infinite darkness, or I could just stay there for a while. So long as I stayed in this room I could go back but it was not so clear if that was the case if I proceeded any farther. I chose to hang out a few moments and then return to the light.

Remarkably, I didn’t turn loose of Harrison or fall down during this spell, but it was truly eerie, and I have never experienced that depth of darkness before. A couple of healthcare professionals I later discussed this with have told me it was a classic symptom of shock.

When I finally released Harrison he ran back into the house screaming frantically, “You bring Curtis back! Bring him back now!” I told him I couldn’t do that.

[InContentAdTwo]

He grabbed the telephone, yelling that he was calling Curtis. He demanded the phone number. I could only tell him through tears that you can’t call people on the phone after they have died. “He’s gone, son.”

Harrison’s rage over Curtis’ death did not subside that day or even over the following weeks, during which he was suspended from school three times. The staff at school began to work on the subject of death with him. They had me send photos of Curtis and Harrison to create a social story, resulting in a short booklet called “My Friend Curtis.” A month later, the subjects of death and Curtis remain a tense focus with Harrison.

My last conversation with Curtis was over the phone just a couple weeks before he died. We were discussing Harrison and I remember him saying, “Harrison is writing his own rules.” I have thought about this many times since Curtis’ passing, and I am sure I will reflect upon it many more times in the future.

I didn’t know it then but it was one final gift of wisdom that I will carry onward with me on the rest of this journey until at last I cross that great pass myself.

Hal’s books Full Tilt Boogie and Endurance are available from The Book Haven in Salida.

Thank you for writing this….

Beautifully written