By Virginia McConnell Simmons

The economic potential of booming mining camps inspired the board of directors of Colorado Springs’ First National Bank to build a standard-gauge railroad through the Rockies. They believed they could provide the mountain region with better equipment and service than the region’s miniature railroads were already doing. The optimistic capitalists of “Little London” soon learned some hard lessons about pitting money and machinery against the high country.

In 1885, they elected John James Hagerman as president of their proposed Colorado Midland Railway (CM), a year after he arrived in Colorado. He was in his forties, had already made a nice fortune in iron mining on Michigan’s mostly-flat Upper Peninsula, and had lived on the urbane Continent, seeking a cure for his tuberculosis. Once in the Pikes Peak Region, he energetically set about leading the railroad project and raising capital.

The initial objective was revenues from Leadville and Aspen, along with coal from around Redstone and New Castle – where Hagerman invested – and from agriculture. Arranging a traffic agreement with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad, the Midland was competing with the roundabout narrow-gauge Denver & Rio Grande, which, despite its earlier start, still barely beat the CM into Aspen. However, the CM’s original plan to build to Salt Lake City after reaching New Castle and Grand Junction became financially impossible.

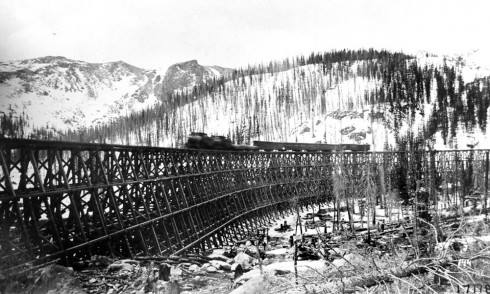

Work started at both the eastern terminus and the soaring crest of the Sawatch Range, where tunnel construction would be required. Perhaps having second thoughts while constructing eight tunnels and a four-percent grade in Ute Pass, they attacked the Continental Divide itself. There, with a camp at Douglass City, they constructed huge trestles and the Hagerman Tunnel in 1888, 2,016 feet long at 11,528’ elevation near the top of Hagerman Pass (11,925’ el.). Mired in construction costs and often closed by deep snow, the CM nevertheless soon spent more money, relocating slightly lower and boring the much longer Busk-Ivanhoe Tunnel in 1893; 9,394 feet long, at 10,948’ elevation.

Alas, an economic blow had already struck. Silver mining collapsed and the Panic of 1893 ensued. Mining and smelting at the Cloud City would continue to produce revenues from gold and non-precious metals in future years, but the CM’s ultimate fate was predicable.

In contrast, the gold rush began at Cripple Creek in 1890, and from there it was downhill all the way to the bank for Hagerman and others who invested in gold mines. They constructed the Midland Terminal Railway (MT), a short line to connect to the CM line at Divide, and, eventually, the Midland Terminal would take over the remaining Colorado Midland property until the MT itself was finally dismantled in 1949.

Meanwhile during WWI, the U.S. Railroad Commission, in a misguided attempt at efficiency, had assigned all rail traffic in the high country to the Colorado Midland, regardless of the CM’s deteriorating physical condition and inadequate administrative capability. Traffic became hopelessly clogged, and the Commission’s decision was rescinded. Few sources of revenue remained other than income from the MT’s use of CM property and occasional freight like limestone being shipped to sugar mills in eastern Colorado. Not surprisingly, the Colorado Midland was abandoned in 1918, and its trackage west of Divide was dismantled in 1921.

Today, the route offers buffs many historical and scenic opportunities, which are accessible or visible from late spring through autumn. Present roads frequently lie on the former railroad grade, like a final insult.

The following tour, from the west side of Colorado Springs to Glenwood Springs, begins at the large CM/MT roundhouse (1887), still standing at U.S. 24 and South 21st Street. The route passed through Manitou Springs (depot converted to a home), crossed Ruxton Creek, and climbed Ute Pass, where tunnels are visible from the highway below. At Divide, the MT connected to Cripple Creek.

Past Florissant and Lake George the CM’s route lay in Elevenmile Canyon (96 Rd) to South Park, where tourists, riding well-appointed equipment, enjoyed wildflower excursions and fishing. Later inundated by Elevenmile Reservoir, rails served ranches at Howbert, Spinney, and Harstel. Tracks for the CM and the Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad both met at Antero Junction (U.S. 285 & U.S. 24).

The CM climbed Trout Creek Pass to the top (9,346 el.) and overpassed the D&SP track, where fill is still visible, then descended to the CM’s Newett Quarry Spur (1886) and passed McGee’s and Yale farther down the pass.

Autos can access a scenic overlook and the CM station site on the east side of the Arkansas River. Carriages and wagons reached its station by crossing the river, because the D&RG had rights in Buena Vista. The CM then crossed a creek northward (trestle abutment extant) and followed the east side of river (375 Rd,) through four tunnels (extant) and Princeton, Riverside, Barre, and Fisher. Granite had a two-story CM depot on east side. The CM crossed to the west near Clear Creek, then passed the old Hayden Ranch to Snowden and Arkansas Junction (Malta).

From Arkansas Junction, the CM reached Leadville, with a large, two-story depot below Harrison Avenue, roundhouse, and shops. The CM served Leadville’s mines and smelters until 1906, with tracks in Iowa Gulch and California Gulch.

Following FR 105 from Arkansas Junction, the CM route passed between Sugarloaf Mountain and Turquoise Lake to Busk Creek and Hagerman Pass. The Busk-Ivanhoe Tunnel was used for a few years by autos with the name Carlton Tunnel, with a caretaker and a traffic light controlling one-way traffic. The Busk-Ivanhoe Tunnel next became part of the Fryingpan-Arkansas water diversion project. A steel gate prevents tunnel trespass. Beyond Busk-Ivanhoe, FR 105 (4WD) crosses Hagerman Pass.

The CM passed down the Fryingpan River to Basalt and built its branch into Aspen (1888). CM used the north side of the Roaring Fork to Carbondale and crossed west to serve the Cardiff coke ovens near Glenwood Springs. The CM’s depot at Glenwood Springs was on the west side of town.

Virginia McConnell Simmons is the author of several books, including Ute Pass, Bayou Salado, and The Upper Arkansas. Excellent volumes about the Colorado Midland are by Edward M.“Mel” McFarland and by Dan Abbott with Richard A. Ronzio.