Article by Lynda La Rocca

History – September 2008 – Colorado Central Magazine

BEING A PERSON whose fantasies revolve around escaping to another time, one that I usually (and incorrectly) perceive as kinder and gentler than the age I’m living in, I feel right at home in Fairplay’s South Park City Museum.

Strolling the wooden boardwalks of this historical attraction that recreates life in a South Park mining town from 1860 to 1900, I imagine myself dressed in a long skirt, bonnet, and shawl, a basket on my arm. First, I head to Simpkin’s General Store to purchase flour and coffee and splurge on a tin of what are advertised as “wonderful afternoon tea chocolates.” Then, after finishing the errands, I meet the girls for a soda flavored with strawberry syrup from the new-fangled soda fountain at the J.A. Merriam Drug Store.

Ah, that slow pace, those simple pleasures. This is my idea of the good life. Or at least it would be until I feel a bit under-the-weather and have to rely on the bizarre remedies sold in the drugstore’s patent medicine section, or I need relief from a raging toothache and wind up being poked, pinched, prodded, and punctured by sharp, nasty-looking dental instruments that could have come straight from Dr. Frankenstein’s laboratory. And as for the joys of motherhood, I’d first have to endure delivery by “obstetrical tool with screw lock,” an implement resembling a gigantic pair of metal salad tongs.

OK, I’m convinced: Life for 19th-century residents of high-country Colorado mining towns was far from idyllic. In fact, it was often dangerous, dirty– and damn short. For further proof, I need only look at an old photograph of what at first appears to be a peacefully slumbering infant in a lace-trimmed gown. The baby is actually lying on its bier in the South Park City morgue; the adult-sized, white-satin-lined casket behind this memorial photograph was made to order by a carpenter who doubled as the town undertaker and plied both trades within a single building.

A magnet for early 19th-century hunters, traders, fur trappers, farmers, and cattle and sheep ranchers, South Park became a prospector’s paradise when gold was found in the gravels of Tarryall Creek during the summer of 1859. Soon silver, lead, and zinc were also discovered in this region, spurring the growth of settlements that prospered until the mining boom inevitably went bust. By the 1950s, South Park’s mining camps were crumbling into ghost towns, their remaining structures slowly succumbing to the ravages of time and vandalism.

That’s when Colorado Springs attorney Leon H. Snyder stepped in with an ambitious plan to preserve the area’s heritage by moving historic buildings from surrounding towns to a single location on the outskirts of Fairplay. The site of South Park City is not far from another well-known attraction in downtown Fairplay: The monument to Prunes, the legendary burro that worked the local mines for more than 50 years until his death in 1930 at age 63.

Since its 1959 opening, the South Park City Museum has expanded from a handful of buildings, including seven that were originally on-site, to 43 restored buildings and related structures; the latter includes a narrow-gauge locomotive, rolling stock, and an 1880s railroad water tank. The community’s homes, shops, and businesses are arranged to flank its “Main Street” and contain more than 60,000 period items and artifacts; many of which were collected or donated by local residents and civic groups.

Some of the most eclectic items belong to the Sumner Collection. Housed in what was originally one of Fairplay’s first private residences and donated by the Sumner family of Lake George, this extensive exhibit is a miscellany of trapping, ranching, and mining equipment, Victorian-era household items and accessories, military uniforms, guns, pocketknives, and coins. Among the most unusual objects are a real “nest egg,” a wooden oval painted white that was placed in a nest to encourage a hen to continue laying there (no wonder my late chicken-farmer uncle in Maine used to describe these birds as the “dumbest things” ), and a decorative sword fashioned from the long, upper-jaw “beak” of a swordfish. The work of Joshua Sumner, who came to Colorado in 1871, this sword is exhibited alongside a wooden carving of a sperm whale made by Sumner while on a voyage to the South Pacific in his whaling ship.

Inside an early U.S. Forest Ranger Station, my husband Steve and I find the horn of a bighorn-sheep ram sitting on a shelf. Like many South Park City artifacts, it is there for the taking. (“People who come to places like this don’t steal things,” a volunteer from the South Park Historical Foundation says when I ask about the lack of security. And long may such confidence in humanity’s integrity reign!) Unable to restrain our curiosity, Steve and I both heft the horn, which must weigh at least 10 pounds. Imagine walking around with two of those things protruding from your head.

At the Wagon Barn we examine a covered chuck wagon complete with a “chuck box” to hold cooking utensils, pots and pans, and staples like canned goods, and a dilapidated wagon stacked with cottonwood-tree logs. These logs were bored by hand in 1882 for use as Fairplay’s water line– and were not replaced until 1960.

Historically accurate and elaborately carved and painted mining dioramas by Denver artist Hank Gentsch, who also made the mining dioramas in Leadville’s National Mining Hall of Fame & Museum, are showcased within both the 1879 South Park Brewery and a small cabin on Main Street.

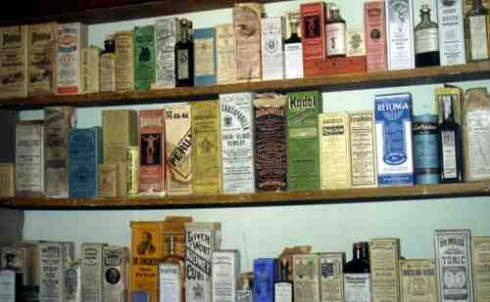

But my favorite stop is the 1880 J.A. Merriam Drug Store. Originally located in Alma, this enterprise sold everything from penny candy and stationery to jewelry and cosmetics like “DeWitt’s Toilet Cream, A delightful toilet article– positively harmless.” I could spend all day in this drugstore, just reading the labels of what is reportedly one of the most complete collections of patent medicines in the United States. Purchased at an auction in Westcliffe, these bottles and tins hold rather alarming-sounding curatives like “Worm Candy,” “Bees Laxative Cough Syrup,” “Swamp Root,” “McLean’s Volcanic Oil Liniment,” and the mysterious “Elixir of Wahoo.”

Some of these concoctions contained more alcohol than the drinks served at Rache’s Place saloon and gambling house across the street. Others were made with plant extracts now known to be toxic, physically addictive, or hallucinogenic, properties that may have made users at least believe they were indeed living the good life– if the ingredients didn’t combine to kill them first.

Ltnda La Rocca writes from Twin Lakes.