By Martha Quillen

Courtesy of Citizens United, there’s now a surfeit of cash fueling the spin, pander, deceptive advertising, resentment, indignation, and histrionics that characterize modern campaigning.

But it’s not the money that’s driving Americans insane, it’s the inherent duality in our psyche. We regard ourselves as good and bad, right and wrong, Republicans versus Democrats, and us versus them. And in recent years, we’ve started casting ourselves as warring factions too divided to ever cooperate, like the North and South, and Allies and Axis.

So what’s happening now that there is an unending stream of money, time and ingenuity pouring into politicking? We are losing our collective minds. Look at how we campaign. The object is not to illuminate the issues or present workable solutions, it’s to convince people that they must defeat their enemies.

During our last election season, Salidans cleaved themselves in two and labeled the pieces “Moving Forward” and “Taking Back.” Some people actually said they were voting for “Moving Forward” because it sounded better. And one Citizens for Accountability in Government member assured me that their slogan was not “Take Salida Back,” it was “Take Back Salida.”

But that makes no difference because it’s not the words that are doing us in, it’s the battles. Every month there’s a new proposal to wrangle over: a new boat ramp, groover, water park, skating rink … Improvement plans flow faster than the Arkansas, with one side yelling “stop” and the other “go.” And with both sides locked in combat, the city does what it wants, which is apparently to convert Salida into someplace else in record time.

Once upon a time, Salida was slow, stodgy and resistant to mainstream trends. It took more than a century for us to replace our old hospital. Then suddenly our city surpassed being progressive and took to improving at warp speed. Now the city’s got no time to tarry, or even inform citizens before it shuts down streets, cuts down trees, or destroys sidewalks. Damn the torpid people, it’s full-speed ahead.

Recently, Darla Andrews wrote to The Mountain Mail after the city yanked out her sidewalk without informing her first. “Salida did me dirty,” she wrote, vividly complaining about the mess they’d made of her landscaping.

Andrews’ tale resonated with me because my own sidewalk is not so stellar that it couldn’t be next. And her letter worried me because it didn’t sound as if our city crews would show my trees and honeysuckle bushes any mercy if they got in the way.

Nor did the city make it clear who would have to pay to replace the sidewalks – just like it hasn’t made it clear when we will have to purchase new water meters.

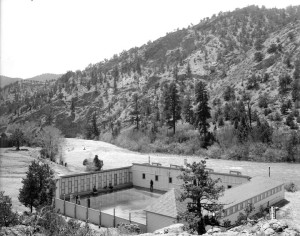

Then the city started talking about putting in new outdoor swimming pools and a skating rink, and I started thinking that if I wanted to have any money left so I could retire before I’m eighty, I should either start protesting immediately or move.

After reading Andrews’ letter, I asked my co-workers if they knew anything about who was supposed to pay for new sidewalks and when we would have to spring for new water meters. No one did, but one of them had read a notice for a city sidewalk meeting.

So I went, and as it turned out, Michael Yerman, the city’s Community Development Director, didn’t know who was going to have to pay for the sidewalks, either, or when they’d be finished. “Maybe not for years,” he said, but that was a matter for the city council to decide. In the meantime, the city had enough money to remove bad sidewalks, so it was taking them out.

To facilitate the process, Yerman instructed us on how to use the colored markers and maps provided to indicate which sidewalks we used most in order to help the city determine which sidewalks to do first. I thought the project was incomplete, haphazard, and more likely to annoy Salidans than serve them – since the temporary road-base walkways the city was installing didn’t strike me as any safer for vulnerable people with walkers, wheel chairs, or baby carriages than the warped sidewalks.

But what did I know? I hadn’t conducted any walkway safety tests. So I marked the routes as instructed, but was left feeling compliant in the city’s questionable annihilation program.

Since then, the city has immersed itself in several new controversies, and our council has gotten so sensitive about objections and “negativity,” that it is fashioning a code to make it clear how citizens must conduct themselves at meetings and what council members are supposed to say. (So much for our First Amendment rights.)

W

hether people are aware of the research on such matters or not, Salida is immersed in a classic “gentrification” battle, with its citizens wrangling over project after project. Gentrification is a term used to describe what happens when wealthier people move into working-class areas and fix them up. It was first coined in 1964 by Ruth Glass, a British sociologist, after young professionals started buying up tired old mews and cottages in working-class London.

“Once the process of gentrification starts,” Glass wrote, “it goes on rapidly until all or most of the original working-class occupiers are displaced and the whole social character of the district is changed.”

But that isn’t how things proceeded in Salida.

One of the first steps toward gentrification often occurs when artists and bohemians move into depressed neighborhoods because they’re cheap. The artists aren’t rich and don’t want much, but they spruce up deteriorating neighborhoods, fix up buildings, and open trendy shops and restaurants which attract young professionals, who move in, buy homes, and demand more services and infrastructure. Then taxes, utilities, and housing prices soar, and the artists and old-timers have to move out because they can no longer afford the place.

Salida started heading in this direction more than thirty years ago, but got stalled in the initial stage – until recently, when our progress was prodded back into life by considerable investment, including a lot of public investment. Now we’re in the midst of it, and the costs are starting to rise.

Gentrification is a painful, problematic, and unfair process, but it’s also a proven asset to economic development, so it’s usually encouraged, and there are scads of materials available to help mitigate the pain.

But the City of Salida and its supporters keep dismissing what’s happening. It’s just those naysayers, they contend. They’re ungrateful, cheap, outmoded, and want something for nothing. Supporters seldom express a smidgeon of concern about the city’s plans, budget, or how improvements are being financed, which is ironic, because, by the time it’s clear whether Salida will become a third-rate Park City, second-tier Moab, or bankrupt wannabe Aspen, most of the opponents will have moved on.

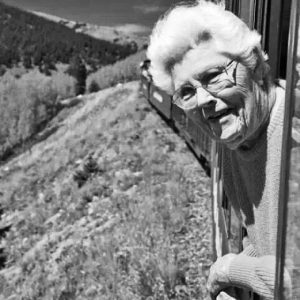

I will miss the old Salida, which was friendly, funky, low key and affordable; in fact, I already do. But what I will miss more is something that may have only existed in my mind: a serious, inclusive, fair political process that makes sense.

Martha Quillen lives in Salida and loves swimming pools, but can’t afford to buy one.