By Jamie Devine

The infantry run their daily drills, the smell of sulfur lingering in the air. The cavalry are mounted and heading towards the area of patrol, their horses galloping by and kicking up dirt. The officer signs off on papers in his office, while the sounds of the blacksmith’s forge clang in the background. Children are playing in the parade ground as their mothers chat among themselves. This would have been a typical scene at a military fort in the mid-19th-century West. Yes, women and children did live at military forts. They lived and interacted among the soldiers in a male-dominated environment.

With the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which formally ended the Mexican-American War in 1848, the area we now know as New Mexico and Southern Colorado was ceded to the United States. At that time, the population was overwhelmingly Hispanic. In 1853, the U.S. government established Fort Massachusetts, in a canyon on the east side of the San Luis Valley, to control Ute Indian raids on local Hispanic settlements.

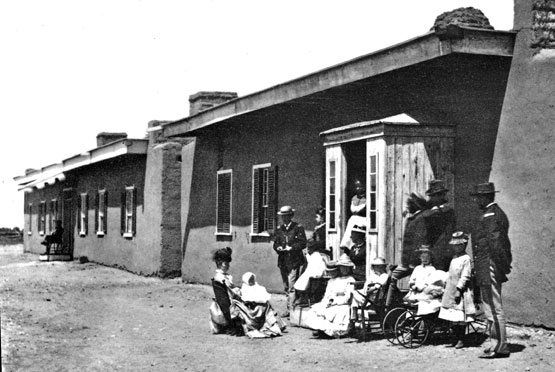

In 1858 the installation was moved about six miles south, onto the valley floor, and renamed Fort Garland. Fort Garland is nestled in the San Luis Valley, with a stunning backdrop of the Sangre de Cristo mountain range. In addition to the protection it provided, Fort Garland was an economic driver; it became the primary consumer of local hay, produce, and lumber, and the source of many civilian jobs. After being involved in several major military campaigns, the fort was abandoned in 1883.

Many officers stationed at Fort Garland had their families living with them. They lived on Officers Row, which is the northern set of adobe buildings. Kit Carson was stationed at Fort Garland for one year, and during that time he had his wife Josefa and their five children living with him. Non-comissioned officers, as well as laundresses, would have also had their children living at the Fort with them. Although we know that children lived among the soldiers at Fort Garland, there is mention of them only in passing in the historical record. What remains are a few photos of these children, and the remnants of their toys scattered throughout the fort property.

These toys left behind by the children are a reminder of what life was like at Fort Garland; not just soldiers running through their daily drills, but children playing and living among them. Not much work In archaeology has ben devoted to studying children, but children play an important part in any society. They reflect how we view ourselves. What we buy for them to play with, how we dress them, how we interact with them: all are part of the messages we as parents are sending out to children to prepare them for their growth into adulthood. Toys are part of the archaeological record at Fort Garland, and by looking at them, we can decipher more of the story of how the fort functioned.

Fort Garland was in commission while the Victorian period in America was in full swing. Victorians believed that women were the center of the household, and that the mother was the symbol of purity and piety. Men on the other hand were encouraged to go outdoors and were viewed as wild and untamed. Children were viewed as angelic creatures, gifts from above. Their clothing and material culture (stuff) reflects this. Younger children, girls and boys alike, had similar hair length and wore white dresses; the logic being that if children are angelic in nature, then they must not be identifiably male or female. Hence the androgynous appearance of Victorian children.

However, although the Victorians had their children appear androgynous, those little children would eventually grow up to live under strictly gendered social rules. Women’s place was in the home, and men provided for the family and worked outside of the home. Toys were instrumental in teaching children to understand these social principles. Girls were encouraged to play with porcelain dolls, paper dolls, and miniature tea sets, while boys were encouraged to play with leather whips, marbles, and toy soldiers.

An archaeological survey was conducted at Fort Garland in the spring of 2012, specifically targeted towards finding toys on the surface. The finds were interesting, to say the least. There were a staggering number of “girl toys” when compared to toys associated with boys. For example, 60 doll head pieces were found, and only three clay marbles. In archaeology, attention must be paid to anomalies like this. Why were there so many more remains of toys for girls? What, if anything, does this tell us about how they loved, what they thought? How they viewed themselves? Archaeology is about people. One has to remember, In examining an artifact, that it used to belong to a person, and attempt to find out how that person used that artifact, before reaching any conclusions concerning what it reveals about the person. These toys, and their condition, tell us something about the environment of the Fort. Porcelain dolls were made to be fragile. That fragility encouraged little girls to be gentle, to be nurturing. At Fort Garland, there were many porcelain fragments of miniature tea sets and of dolls. This may indicate that, despite the fragility of their playthings, these little girls spent quite a bit of time outdoors with them.

And because these little girls were outside frequently, they would have interacted with the soldiers stationed at the Fort. There are several written accounts of little girls being raised in a military fort, and they were treated like little princesses by the men. I believe that this social dynamic, so emblematic of the larger gender dynamics at play in Victorian society, was playing out at Fort Garland as well.

Several small white porcelain dolls were found in various areas of Fort Garland. They are called “Frozen Charlottes,” and are named after a semi-legendary figure: a mid-19th-century poem based on a newspaper account, and later set to music, reveals that Charlotte was, in fact, a girl of about 15 years of age. While she was getting ready for an evening party, her mother warned her to put a coat on for the sleigh ride there, or she would freeze to death. Charlotte, who had her new dress on and wanted everyone to see it, told her mother she would not put a coat on. Her beau placed her on the sleigh and by the time she reached the party, she had frozen to death. The moral of this story, doubtless repeated to many disobedient little girls during the Victorian period, was to heed to your mother’s advice, or suffer dire consequences.

My own children have helped me to understand childhood for these children at Fort Garland. They helped me make clay marbles, and accompanied me through countless antique stores as I compared antique dolls. Having my own children assist me in my research, has enabled me to have a different perspective as I uncover the stories of the little ones who lived at Fort Garland.

Jamie Devine is an archaeologist and a mother of two. When she is not digging for artifacts, then she is digging in the dirt in her garden.