Article by Merritt R. Blakeslee

Geography -April 2006 -Colorado Central Magazine

IN 1949 TWO GEOLOGISTS in the Denver office of the U.S. Geological Survey were assigned the task of updating the geological description of that portion of Gunnison and Chaffee counties covered by the USGS Garfield Colorado 15-minute quadrangle. The geology of this area had been cursorily surveyed by the Hayden Survey1 and was the subject of a detailed study in 1913;2 and the two geologists were charged with bringing this previous work up to date.

The project was an important one, as the Garfield Quadrangle had seen some of the most profitable mining activity in the entire state during the last two decades of the nineteenth century and the first two decades of the twentieth century. The project lasted eight years and was published in 1957 as McClelland G. Dings & Charles S. Robinson, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Garfield Quadrangle, Colorado.3

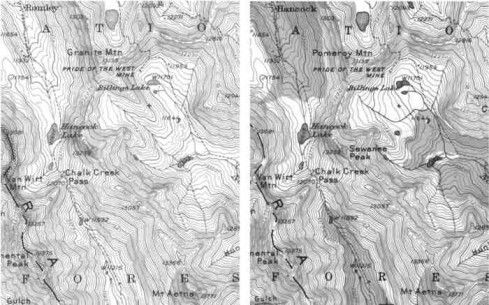

Incidental to their central mission was that of correcting the topography of the quadrangle, first sketched out by the Hayden Survey in 1873. When first surveyed by the USGS between 1938 and 1940, the Garfield Quadrangle had been surveyed by traverse plane tables with open-sight alidades, a technique rendered obsolete by aerial photography. As Dings and Robinson proceeded with their geological survey, they quickly became aware that portions of the USGS quadrangle published in 1945 were inaccurate.

Dings and Robinson resurveyed the Whitepine and Tin Cup mining districts using the same plane table techniques and telescopic alidades used by the original USGS surveyors. By then, however, the remainder of the quadrangle had been photographed aerially, so, using a Brunton compass, a hand level, and an altimeter, they established the locations of outcrops throughout the problematic areas, thus permitting the USGS cartographers in Denver to correct the topography of the 1945 quadrangle by tying the existing map to the new aerial photographs.

Surveying the geology and correcting the geography involved walking the entire area of the Garfield Quadrangle, although “walking” is a pale description of what the job actually entailed — the strenuous navigation of steep, rocky peaks, often up and down slopes covered with loose talus, while carrying heavy, antiquated surveying equipment. This was primarily a geological (and only secondarily a geographical) survey, however, and geology means rock samples. So the “walking” also involved carrying back geologic specimens — rocks — to be sliced into microscopically thin sections for examination by light refraction for their mineral properties.

In 1951, Dings was reassigned to a project on the Front Range, leaving Robinson with the responsibility for finishing the Garfield Quadrangle project. “But he looked over my shoulder, even after he left,” Robinson says.

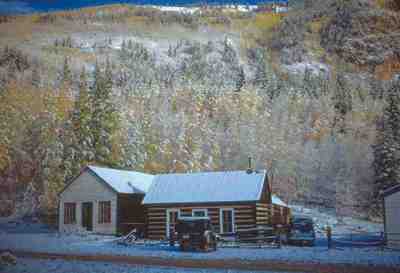

Robinson spent four summers — from 1948 through 1951 — in the field. During the summer of 1948, he and Mac Dings worked out of Pitkin and lived in the Pitkin Hotel. During the summer of 1949, Robinson and a colleague known as “Cornpone” (his real name was Donald Whitebread) worked out of Whitepine. Robinson got married in February 1950, and he and his bride, Elizabeth Hale, spent the summers of 1950 and 1951 in St. Elmo, at the confluence of Tincup Creek4 and the upper Chalk Creek drainage.

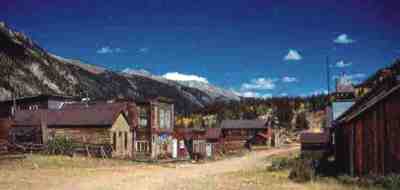

In those years, St. Elmo, which little more than a half century before had boasted perhaps as many as 1500 to 2000 citizens,5 had only two year-round residents, Tony Stark and his sister, Annabelle Stark Ward — although five or six summer families had bought up old mining cabins and fixed them up as vacation cottages.

The Stark family had built the first house in St. Elmo in 1880.6 Tony Stark was an old telegraph operator from the Denver, South Park & Pacific Railroad, which ran through St. Elmo until 1926. Annabelle, who had a college education, beauty, charm, and fashionable clothes, moved to St. Elmo sometime before 1910 so she could care for her two brothers after the death of her mother. There, she became known as the “Queen of St. Elmo.”7

Tony and Annabelle operated the Home Comfort Hotel and the Stark Bros. Store. The store housed the post office, which they also ran. Notwithstanding St. Elmo’s tiny population, “it usually took about two hours for them to get the mail s orted and put up after it arrived … because the Starks had to read it all first.” In 1952, the year after the Robinson’s last summer in St. Elmo, the post office was closed.8

“We lived in a log cabin with no heat except a wood stove and no electricity. My wife loved it,” Robinson recalls. Only two houses in St. Elmo had running water. “Ours was one. At least it was after I took the dead cow out of the intake. The pipe that brought the water into the house ran through a heating coil in the wood stove. On Saturday afternoons, my wife would put something in the stove that needed to cook for a long time, baked beans or bread. Most of our neighbors would stop over. They all took hot showers, one after the other. Then we had a big picnic.”

Unlike the summer people, however, the Starks were not partial to showers or other common forms of personal hygiene. “Annabelle never took a bath. And they kept caged animals in their store. Between them and the animals, the place smelled like hell.” In 1958, after Annabelle suffered an accident, it was discovered that she and her brother “were both suffering from malnutrition and that they were living in filth. The home had one room full of firewood; another was piled high with newspapers, bones, decayed food, tin cans, clothing and bags full of silver dollars!”9

Robinson climbed on and over Sewanee Peak many times. “You have to cover every square foot of what you are mapping. Once when I was on the summit ridge of Sewanee, I found myself thinking, ‘No one has ever set foot up here before.’ A few minutes later I found an empty Coors bottle from 1890 lying in the bottom of a shallow prospect hole!” Like other geologists before him,10 Robinson greatly admired the western face of Sewanee Peak, which presents a particularly striking example of a contact zone between two geological bodies: Mount Pomeroy quartz monzonite and the darker quartz latite porphyry of which Sewanee Peak is made.

* * *

Robinson was born in 1920 in East Lansing, Michigan, where his father was a member of the Experimental Chemistry Department of the Department of Agriculture. The family lived there until 1931, when his father joined the faculty of the Vanderbilt School of Medicine in Nashville, where Robinson attended the Peabody Demonstration School. When he graduated in 1937, his father urged him to apply to the University of the South in Sewanee. “Dad had a great respect for Sewanee” and particularly for Roy Benton Davis, Sewanee’s professor of chemistry; and his urging prevailed. Robinson matriculated in 1937, a member of the class of 1941, and attended for two years.

The University of the South, “Sewanee” to all who know it, was founded shortly before the Civil War by the Episcopal dioceses of the southeastern United States. It occupies a large, wooded domain — the second largest campus in the United States — on the rim of the Cumberland Plateau in southeastern Tennessee, roughly halfway between Chattanooga and Nashville. While the college is known as “Sewanee,” the domain — and, by extension, the college — is usually referred to simply as “The Mountain.”

From the beginning, Sewanee modeled itself on Oxford University, and it has, over the years, produced a disproportionate number of Rhodes Scholars. Even today, professors teach in academic gowns, and the Order of Gownsmen, admission to which is by academic achievement, provides the school’s student government.

Sewanee is a place of great physical and architectural beauty, a distinguished academic and intellectual tradition (the Sewanee Review is the oldest continuously published literary review in the United States), and a pervading sense of both place and history. It is a true statement that Sewanee exercises an unusual attraction over those who — like Charles Robinson — have come to know it.

During the summer between his freshman and sophomore years, Robinson studied geology at the University of Michigan. In 1939, he transferred to the Michigan College of Mining and Technology (today Michigan Tech) in Houghton, Michigan in order to continue the study of geology — Sewanee having no such course in its curriculum at the time. The war interrupted his studies, and he graduated hastily in 1942, before completing his work in geology.

After the war, Robinson found himself without marketable career skills, so he enrolled in the doctoral program in the University of Colorado’s Department of Geology. He completed his course work before joining the USGS in 1948 and finishing his dissertation in 1956.

Robinson spent seventeen years in the USGS. Since then, he has worked as a private-sector geologist and engineering geologist throughout the Rocky Mountain West. Today, he lives in Golden, Colorado; is president of his own company, Mineral Systems, Inc.; and continues to practice as a consulting geological engineer. He has published more than forty articles and books.

* * *

Crawford, the author of the map from which Robinson and Dings worked, candidly admitted to a certain element of imprecision in his work: “Traverse plane-tables with open-sight alidades were used in both triangulation and traverses…. It is too much to hope that, with the instruments used, there are no errors in the topographic map. However, … [i]t is not probable that many of the contours are in error more than two contour intervals.”11 The contour intervals on the Crawford map are 100 feet.

But in Robinson’s considered view, formed after all that “walking,” the errors were more significant than Crawford admitted … in some cases by a factor of ten. “The old map was full of errors. One 13,000-foot peak was shown as only 11,000 feet. It used to make me mad every time I had to walk over it.”

Robinson and Dings communicated their corrected survey data directly to the USGS in Denver. But Dings had charged Robinson with correcting all of the errors in the 1945 Garfield quadrangle, not just the topographic errors. The USGS proposed to reissue a corrected version of the 1945 edition of the Garfield Quadrangle in 1953. Robinson, who was then on a tour of administrative duty in Washington, D.C., wrote to the Board on Geographical Names of the USGS to propose a series of corrections and additions to the nomenclature of the Garfield Quadrangle.12

Robinson informed the Board that in the process of carrying out the geological mapping of the Garfield quadrangle, “it was noted that several names on the published topographic map did not agree with the names used on earlier maps or with those in local use.”13 Robinson pointed out, for example, that the name “Romley” was erroneously attached to the site of the old town of Hancock, and that the real Romley was actually 2 and 1/2 miles to the north down Chalk Creek. “The postoffice building in Romely [sic] is still standing, with the name on it.” He proposed restoring the name “Pomeroy Mountain” to a peak shown in the 1945 Garfield Quadrangle as “Granite Mountain,” one of several so named in the immediate vicinity, because “Crawford used this mountain as his type locality for the rock type termed the Pomeroy quartz monzonite.”

Finally, Robinson wrote, “There are several names of geographic features that we would like to have added to the quadrangle sheet to aid in the description of the geology.” Our sources of these names are Crawford’s [i.e., the 1913 work on the geology of the region] or local usage.14 He proposed adding three such names. Two of these — Lost Mountain and Calico Mountain — do, in fact, appear on Crawford’s 1913 map; indeed, Calico Mountain also figures on Altman’s 1881 map of the region. The third was Sewanee Peak, which has neither name nor elevation on Crawford’s map, and which, on the 1945 Garfield Quadrangle, bears only an elevation, 13,259′.

Even a half century ago, the Board on Geographic Names was not inclined to accept proposed name changes on the strength of an uncorroborated claim of “local usage.” It firmly rejected one of the corrections proposed by Robinson — Tincup Creek for North Chalk Creek — notwithstanding that Robinson cited as his sources for “Tincup Creek” ” the only 2 people living permanently in St. Elmo (old telegraph operators from 1910) [these were, of course, Tony and Annabelle] and 2 old timers at Tincup.” 15

But the proposal for Sewanee Peak passed unchallenged. Indeed, in its comments on the name changes proposed by Robinson (all fell within either the San Isabel or the Gunnison National Forest, making recourse to the Forest Service mandatory), the U.S. Forest Service, which had successfully overruled the North Fork-to-Tincup revision on the ground that “[o]ur Supervisor … after 20 years in that locality has never heard [it] referred to as Tincup Creek,”16 wrote of the proposed “Sewanee Peak”: “Locally accepted. Unknown origin. No further information on elevation.”17

Of the seventeen name changes made by the USGS in Colorado between 1950 and 1954, eleven — including “Sewanee Peak” — were those proposed by Robinson.18 “I had to correct a hell of a lot of names and I just slipped it in.”

Why did he do it? Certainly his sense of humor was involved. & quot;The USGS work [he was pushing a desk in Washington at the time, riding herd over the publication of mineral studies] was pretty tedious.” But, far more than a prank, it was a tribute to a university that had, far more than the two institutions that had granted him learned degrees, imprinted itself upon him.

The first of the Collegiate Peaks to be named were Mounts Harvard and Yale. Their names were conferred in 1869 by a group from Harvard University’s new Hooper School of Mining and Practical Geology (composed of four students led by Professors Josiah Dwight Whitney, the school’s director and one of the most eminent geologists of his day, and William Henry Brewer, a botanist, physical geographer, and professor of agriculture in the Sheffield Scientific School of Yale University). When the Harvard expedition came to Colorado in the summer of 1869, it was in search of a solution to the greatest geographical problem of the day — identifying the highest point in the contiguous United States. And when it departed, it had debunked rumors of 18,000-foot peaks in the interior of the Rocky Mountains and confirmed that Mount Whitney in California was the highest point in the contiguous United States.

Mount Princeton received its name in 1873, when the Director of the civilian Hayden Survey, then locked in struggle for congressional funding with the Army’s Wheeler Survey, champions of a more traditional methodology, named the peak in honor of Arnold Guyot, a celebrated Swiss geologist who, in 1855, had assumed the chair of Physical Geography and Geology at Princeton University.

There is a certain satisfying symmetry between the early geologists and topographers, who named Mounts Harvard, Yale, and Princeton, and Robinson, another geologist and topographer, who, three quarters of a century later, named the last of the Collegiate Peaks.

This article is reprinted, with permission, from the Winter 2005-06 edition of Trail and Timberline, the quarterly magazine of the Colorado Mountain Club, and Colorado Central is grateful. For more information about the club and its good deeds, check its website at www.cmc.org.

Merritt R. Blakeslee is a member of the American Alpine Association and has been climbing in Colorado since the 1960s. He is working on a scholarly history of the naming of the Collegiate Peaks for publication by the Colorado Historical Society. He received a B.A. from the University of the South, and lives in Alexandria, Virginia. He practices international law in Washington, D.C.

SOURCE NOTES

1) F. V. Hayden, Annual Report of the United States Geological and Geographical Survey of the Territories Embracing Colorado, Being a Report of Progress of the Exploration for the Year 1873 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1874) 305-51.

2) R. D. Crawford, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Monarch and Tomichi Districts, Chaffee County, Colorado, Colorado Geological Survey Bulletin 4 ( Colorado State Geological Survey, 1913).

3) USGS Professional Paper 289 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1957).

4) The USGS knows this stream as “North Fork of Chalk Creek,” Robinson having failed to persuade them that it was known locally as “Tincup Creek,” rising as it did on Tincup Pass on the Continental Divide.

5) Louisa A. Ward [Arps], Chalk Creek, Colorado, The Old West Series of Pamphlets, No. 9 (Denver: John Van Male, 1940) 36.

6) John W. Jenkins, “Ghost Towns: Southern Saguache Range,” Trail & Timberline Sept. 1994: 218.

7) John K. Aldrich, Ghosts of Chaffee County: a guide to the ghost towns and mining camps of Chaffee County, and eastern Gunnison County, Colorado, written and photographed by John K. Aldrich (Lakewood, Colo.: Centennial Graphics, c1987) 35.

8) Aldrich, Ghosts of Chaffee County, 35.

9) Aldrich, Ghosts of Chaffee County, 35.

10) Crawford, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Monarch and Tomichi Districts, Plate XIIIb.

11) Crawford, Geology and Ore Deposits of the Monarch and Tomichi Districts, 19.

12) Memorandum dated Jan. 15, 1953, from C. S. Robinson, Geologist, U.S. Geological Survey, to Board of Geographic Names, re: “Proposed changes in geographic names on U.S. Geological Survey Topographic sheet of the Garfield quadrangle, Colorado.”

13) Robinson memorandum of Jan. 15, 1953, 1.

14) Robinson memorandum of Jan. 15, 1953, 2.

15) Handwritten note of telephone conversation on July 28, 1953 between a representative of the Board on Geographic Names and Charles S. Robinson.

16) Letter dated July 7, 1953 from Richard E. McArdle, Chief, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, to the Director, Division of Geography, Department of the Interior.

17) McArdle letter of July 7, 1953.

18) United States Board on Geographical Names, Decisions on Names in the United States, Alaska and Puerto Rico: Decisions Rendered from July 1950 to May 1954, Decision Listing 5401 (Washington, D.C.: Dept. of the Interior, 1954).