By Mike Rosso

It’s quite likely there may never have been an arts scene in Salida without the arrival of sculptor Chris Byars. One of the ironies of this is that many recent artists to town have never even met the man.

While on a back roads tour of Colorado in 1971, the Denver native stopped in Salida to visit his older brother Jack, who was living there at the time. The following weekend, Chris followed suit.

It was the plethora of large commercial buildings, at bargain basement prices, that had Byars encouraging his artist friends in Denver to consider relocating to Salida back then. Many ignored his advice, but other more visionary types put the big city in their rearview mirrors and moved to Salida with the possibility of creating an affordable arts scene. At the time, the town was mainly blue-collar workers with a little tourism thrown in. Many of the downtown buildings were empty and boarded up. There was little commerce going on.

“Twenty-five years ago, I never would have believed that someday there would be two dozen artists and galleries here. I sometimes wished for something like that, though,” he is quoted as saying in a Colorado Central interview from 1996. He was also concerned about rising real estate prices and their effect on struggling artists and now admits that little has changed. Even with its Arts District designation, it is a tough place for artists just starting out. “I think it’s a good place for established artists to make it … if you’re at the top of your craft, you’re going to make it,” he said recently. “Personally, I rarely sold anything locally.”

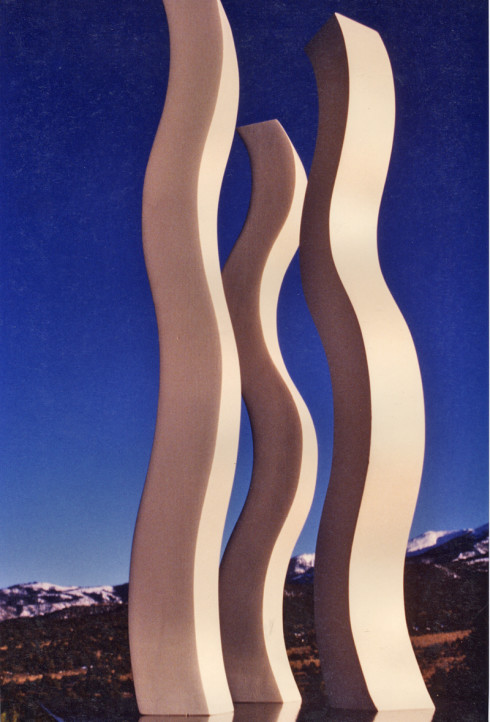

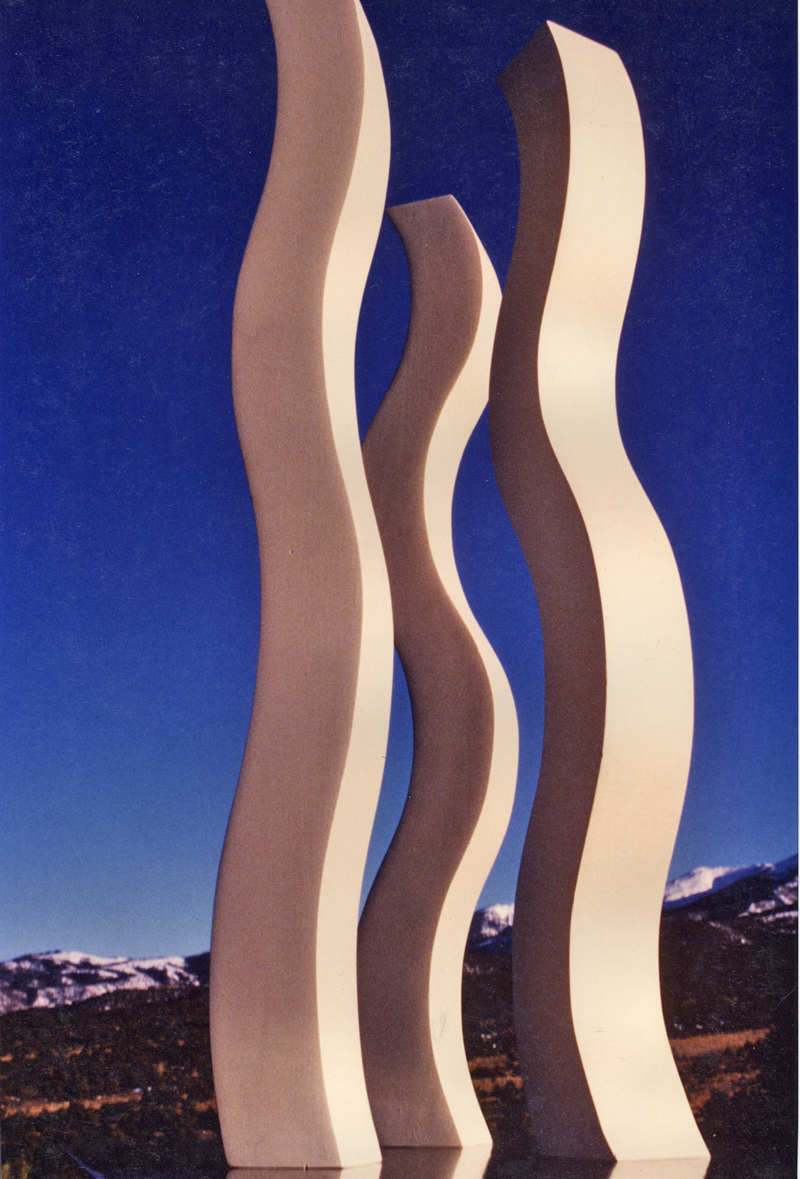

His first large commission – for the then-brand-new Sangre de Cristo Arts Center in Pueblo – is still on display there, 42 years later. In the years that followed, he began to create an extensive portfolio of large abstract sculptures commissioned by various design agencies, including the Alfred Taubman Company, the pioneers of the modern shopping mall.

In that same 1996 CC article, Byars described getting razzed about being the “king of shopping-mall sculpture,” as many of his earlier works were incorporated in the ascetics of those early monuments of retail. In fact, one of his long-standing pieces is still on display at the Cherry Creek Mall in Denver, although it invariably led to his abandonment of corporate commissions. The initial proposal was to have the large metal sculpture on a rotating base with colored lights controllable by shoppers in a glass foyer. “It was supposed to turn at a slow, almost imperceptible rate … always in transition.” Instead, the mall owners decided they wanted a static piece with the lights controlled by a computer. “They took 20 thousand from my commission and gave it to an engineering company who said I couldn’t do it … the steel alone cost $20,000.”

The work still stands outside the mall, but the gels in the lights have faded and trees have been planted in front of it, obscuring the art with each passing year.

“I was so fed up when I got done with that piece, I said f**k it, I’m not doing bid work anymore.”

His son Paul who was born and raised in Salida, explained some of his dad’s struggles: “If the art buyers take you out to dinner, it’s actually going to cost you thousands of dollars ’cause they’ll spend the whole evening trying to talk you down – also they would change the original artwork and that would bum him out.”

Since that time, Chris abandoned the idea of large corporate commissions and begun concentrating on a different style of art closer to home. He began to salvage materials found along the Arkansas while kayaking and welded them into static as well as kinetic sculptures, many of which are still on display at his “ranchito del basura blanca” (small ranch of the white trash) located just east of Salida fronting U.S. Hwy. 50.

He’s lived there, mostly off the grid, since 1979 but continues to create works in a commercial building on 1st Street in downtown Salida that he first purchased in 1974 (at a ’74 Salida price), which he has since sold to his son, who lives with his family upstairs and leases out two storefronts downstairs. Paul recalled accompanying his father to assist with several of his installations around the country and to participate in a number of peace marches, of which his father was a strong supporter. Just out of high school, his father took him to the then Soviet Union for the Great Peace March for Global Nuclear Disarmament in 1988. “He’s kind of a Socialist – he wants things to be more equal.” said Paul.

Chris also took his son to help out on several of his installations including one at a shopping mall in Washington, D.C. in 1985. They camped out in a teepee on the far edge of the soon-to-open mall, frantically trying to meet a deadline, which was continuously being changed on them. Teepees being a rarity in suburban D.C., they attracted quite a bit of attention from some of the locals, including a large truck full of yokels, whom they eventually became pals with.

We had these cool experiences together.” said Paul. “It was great to be a part of his life.

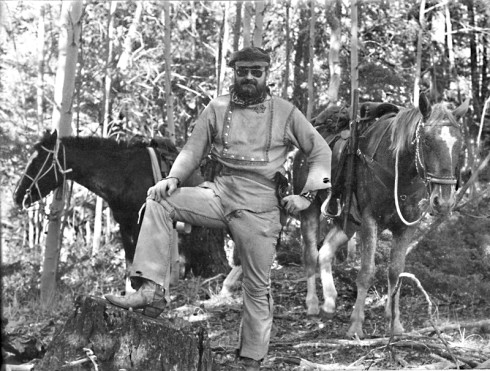

Byars dropped out of high school in the late 1950s and joined the Navy, afterward attending the University of Northern Colorado in Greeley in 1964. There he earned a B.A. in art and was then hired to work in the Cleveland, Ohio school district as a teacher. The mid-60s was a tumultuous time in many American cities, and Cleveland was no different. He personally experienced martial law on at least three occasions. After four years, and a one year stint at the Lincoln Arc Welding School, he returned to Colorado, where he was convinced by sculptor Bob Mangold to go to grad school. Chris did, with the help of the G.I. Bill, attending the University of Colorado in Boulder. He says he was only “one book report” short of a Master of Fine Arts.

In his first year in Salida, he arranged for a year-long independent study from CU. It was during that time that he began to envision, and create, the large abstract metal sculptures that he became known for. Chris estimates he’s recognized nearly half a million dollars in sales over a 30-year career, but is quick to note, “That did not all translate to profit, or my current lifestyle would be quite different.” Much of that income went into materials and transportation, which is one of the reasons he is an admirer of British sculptor Andy Goldsworthy, whose site-specific sculpture and land art requires no material or transportation costs.

Although examples of Byars work may not be very visible in Salida today (he did have a piece at the original Sculpture Garden at the SteamPlant, which now sits rusting behind the building on 1st Street, awaiting resurrection), he has placed sculptures in places such as Denver; a United Way commission; two site-specific pieces in Addison, Texas, a suburb of Dallas, (one of which was used in an ad for the Geo Metro); and a commission for the Universal Oil Products Corporation in Des Plains, Illinois (Chris seethes when he speaks of this, as the last time he visited there, not only was his sculpture decommissioned and missing, the entire building had been replaced). He also did works placed in Gaithersburg, Maryland and Fairfax, Virginia. He still has a piece on display at the Territorial Prison in Cañon City from 1986, a 24-foot steel sculpture, but it has been trashed and neglected with the ultimate insult – Christmas lights were hung from it. According to Paul, his dad got a hold of the prison lawyers and had the ornaments removed.

“It’s now got blisters on it ‘cause they wouldn’t paint the son of a bitch.” said Chris. At one point he went back, hoping to have a look at it, and they “wouldn’t allow me to go anywhere near it.”

Locals can view one piece of Byars’ work at the Heart of the Rockies Regional Medical Center, donated by the late Adrienne Marks. Otherwise, there are examples of his later work scattered among the rabbitbrush on his ranchito, which he’d like to open up for other sculptors to display their work. “I’m in the process of turning it into a place where you can display sculpture … one for anyone who’s got relatively sturdy work, as I can’t pay for insurance.”

Although he says he retired in 2005, he showed me three paper cutouts of a sculpture he’d like to create someday. The three are designed to work in any number of assemblages and at any size. Evidence of his current activity can also be found in the downtown shop, where his son Paul showed me some whimsical metal art his dad had recently welded together out of random metal parts. Chris also entered a design contest for the new World Trade Center after 2001. His model for a 220-foot building was one of 550 that was ultimately rejected. “Had they chosen his design, it would have been finished by now,” declared Paul.

Asked to reflect on his career as an artist, Chris, a self-described eternal bachelor, responded, without hesitation, “I should have been an electrician!”

So nice to see Chris getting the recognition he deserves! It is always nice to see family in print as well. He is an outstanding artist in many media, not just sculpture. Good going, Chris.