Column by Hal Walter

Agriculture – January 2009 – Colorado Central Magazine

A FAVORITE OLD RANCHER once told me: “It’s better to get where you’re going on a slow horse than to go to the hospital on a fast horse.”

Frankly, I avoid riding anything with ears that short.

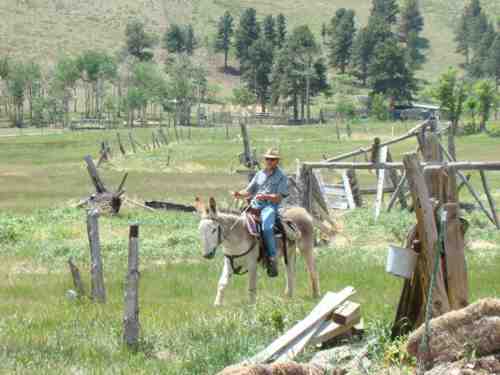

In historical photos from our Central Colorado area it is quite common to see images of people riding burros, or donkeys. It’s easy to guess that burros were the Toyota pickups of the day when veterinarians and emergency rooms were not so common, and when feed, especially in wintertime, was in short supply. Horses may have been the SUV of that era, and mules of course were something in between. Over time the horse and mule have almost fully supplanted the donkey in Western lore, and today we see few people riding burros, though that seems to be changing.

My interest in donkeys began with my involvement in pack-burro racing, Colorado’s only indigenous sport in which competitors race with their equine companions up mountain passes. Riding is not allowed in pack-burro racing, but I can tell you that one does not spend too much time looking at a burro from the ground before he begins to wonder how things look from the animal’s back.

[InContentAdTwo]

One of my first experiences riding a burro was after a long training run with Curtis Imrie back in the early 1980s. We had in fact been out all day and were dead tired. With darkness falling a couple miles out from Curtis’ house, he turned to me and said “You ride, don’t you?” I hadn’t ridden any sort of equine in years, but I climbed aboard Moose and rode him back to Curtis’ house bareback and in the dark. The experience left an impression that never faded.

Today I enjoy riding my burros to gain a different perspective on the country than I get from traveling a little higher off the ground — and I don’t have to pay attention to my footing. There’s also something soothing and therapeutic about the motion of the animal. In fact, we’ve used burro-riding to help with neurological development for my son Harrison, who at age four has his own saddle.

When I first got into pack-burro racing, one of the first things I realized I needed to buy was a packsaddle. I bought a Colorado Saddlery Burro Packsaddle for $175 in 1981, and it is the same one I’ve used in countless races over 27 years. I’ve also used it on a lot of training runs and pack trips with animals of various sizes. All the leather is still original and in good shape, and I don’t think a person can go wrong with one of these saddles for basic packing or pack-burro racing.

But finding a saddle for riding burros has been a different story. When I first started riding my donkeys it was purely bareback. Back then I didn’t really ride often enough to make buying a saddle worthwhile. Over time, however, I became more interested in my donks as riding animals. This interest has paralleled a growing national interest in what is known as “saddle donkeys” or “saddle donks,” and now we are seeing large-breed donkeys bred for this new equine industry. At this month’s National Western Stock Show there will be donkey-only riding events. There’s also a push for gear made specifically for mules and donkeys.

My first saddle was an old McClellan saddle that I found in the corner of a local saddle shop for $50 and then jury-rigged to make it easier and quicker to saddle up. In many respects, this was one of the best choices I made. It is interesting to note that the McClellan was designed for the narrower build of mid- to late-1800s military horses and mules, and would not fit many of today’s horses that have been bred for greater size. But it does come close to fitting modern donkeys. There are numerous ways to adjust its rigging. It is light and can double as a packsaddle. The “centerfire” (one girth) rigging works well on donkeys and keeps the cinch from bunching up on the armpit area. The downside is that a McClellan saddle is hard as a rock and not very comfortable to ride.

I went through a series of other saddles, some of which I bought, rode for a while, and then sold when I found them to be less than ideal. The problem with most of them was that the tree — which is literally the backbone of the saddle — was designed to fit modern horses’ backs, while the back of a donkey or mule is shaped quite differently.

THESE HORSE SADDLES included an Australian saddle with a quarterhorse tree, which in retrospect was way too big for donkeys and also had too much padding between the seat and the animal. But this saddle was easy to sell by consignment at a saddle shop and I actually made money on that deal.

[InContentAdTwo]I parlayed that little windfall into a treeless saddle that was comfortable to ride, but it … well, it wasn’t really a saddle. While there are many people who sing the praises of treeless saddles because of the freedom of movement they may offer the animals, there are just as many people who say these saddles don’t offer enough support to disperse the rider’s weight over the animal’s back and off its spine. That said, I did ride a donkey over Medano Pass to the Sand Dunes and back in this treeless saddle and we both survived.

I replaced the treeless with a synthetic Western saddle built for horses.

This saddle was light, but the tree was still designed for a horse and I noticed it seemed to put me too far forward on the donkey. One day while riding at a trot on a very slight downhill, my donkey tripped and pitched forward, literally landing on his nose. I was launched forward and landed with my head and shoulder hitting the ground simultaneously (the hard head taking the brunt and saving the shoulder from certain injury). I could feel the animal starting to flip over on top of me so I rolled to get out of the way. He, meanwhile, scrambled to regain balance and bounced back up on his feet. Except for a couple of minor scratches, we both were unhurt. But the saddle had to go.

My most recent saddle has been a Steve Edwards Trail Rider Lite, and this saddle has been by far the best. Steve designed this saddle around mule bars that he also developed. According to Steve’s website, he based this mule bar design on the bars used in packsaddles. It’s light at just 18 pounds, and it has a horn.

I’ve had this saddle for nearly a year now and have found my animals seem to move well under it, and it is comfortable for me as well. It doesn’t seem to slip in any direction and there is a close contact with the animal.

One problem in saddling burros and mules is that these animals generally have less pronounced withers than a horse, and thus the saddle tends to slide forward, especially on a downhill.

PACK SADDLES usually come with a “britchin'” which is the rigging used to keep the saddle from sliding forward. While this type of rigging is the only way to go when packing a heavy load, some pack-burro racers instead use a crupper, which runs under the tail to keep the saddle from sliding forward.

While a crupper allows more freedom of movement in the rear end, and eliminates the chaffing that can be caused by a britchin’, some say it can put undue pressure under the tail at a point where a lot of nerve endings come together.

I’ve run a number of tests using both a crupper and a britchin’ and I’ve decided a britchin’ is the only way to go for packing heavy loads, and I also prefer a britchin’ on a riding saddle.

However, in pack-burro racing, when the animal must trot for very long distances and the burro is only carrying 33 pounds, it’s nearly impossible to get a britchin’ rigged exactly right so it doesn’t chaff the rear flanks or limit the range of motion. I’ve gone back to the crupper for training and racing, and have not noticed any ill effects. It is important that the crupper not be adjusted too tightly, and that it be made of good quality leather. The better ones are stuffed with flaxseed.

Recently, a 65-year-old Custer County man died when he was reportedly thrown from a mule while riding near his home in the Antelope Valley area southeast of town. While it’s been labeled a freak accident, this tragic incident is a reminder of the dangerous nature of riding equines whether it be a horse, mule or donkey.

A mule is a hybrid between a horse and a donkey, and can be quicker and more powerful than either of its parents. I’ve had horses try to unseat me, but donkeys actually have put me on the ground before I even knew what was happening. In addition to the aforementioned wreck, I’ve been dumped half a dozen times, twice when donkeys have spooked at something. I’ve never been seriously hurt though I have had my body and ego slightly bruised.

Despite these accidents, I still prefer riding a donkey because they rarely buck and are not as explosive as a horse or mule when they do. Most importantly, they are generally not inclined to run away for great distances or bolt for home as will a horse. Generally, if spooked, a donkey will run a short distance, then turn back to see what scared it. I’ve found it’s often best to just ride it out until the burro stops.

Perhaps there are several keys to the resurgence of the donkey as a riding animal — steadiness, dependability, personality, thriftiness, safety, and the improvement in animals and gear. Regardless, it’s been fun to be along for the ride.

Hal Walter saddles burros on 35 acres in the Wet Mountains, where he also writes and tends neighbors’ livestock.