By Bill Hatcher

Sherlock Holmes is, perhaps, the most famous detective of all time. Recently, he has received renewed attention in film and on television.

However, a different sort of detective has been investigating a real-life enigma here in central Colorado for the past eight years. And if his pursuit seems less glamorous than what happens on the silver screen, his findings have been no less dramatic. This detective is a geologist who has been solving the riddles of a local super-volcano. Doctor Peter Lipman taught geology at Colorado State University in the 1970s, but has been a research scientist since then. He’s now 77 and officially retired. Still, his passion for rocks takes him high into the mountains each summer. And as he told the story, I imagined him puffing on a pipe like Sherlock, pondering.

Eight years ago, Peter was mapping the geology of Cochetopa Park – an area west of the town of Saguache – when he noticed something peculiar. He had stumbled upon samples of welded Bonanza tuff – rocks made from superheated ash – that were over 30 miles from Bonanza. In short, they shouldn’t have been there.

Geologists have long known that the nearby San Juan Mountains were once a volcanic hotbed. The Bonanza townsite itself rests near the center of an ancient caldera – a volcano that collapses after ejecting its supporting magma. A study in the 1980s determined the Bonanza eruption occurred between 30 and 35 million years ago. Researchers from that study called it “a small, incomplete collapse,” which had only deposited ash up to ten miles away. “So,” Peter said, “(the 1980s team) thought that compared to the areas around Creede this was a small-potatoes eruption.” But after hunting around, Peter found rocks that matched the chemical makeup of Bonanza tuff as far away as Cañon City. Peter remapped the geology and what he found was astonishing. Instead of 10 cubic miles of ash, the Bonanza volcano had erupted 250 cubic miles of ash – 1,000 times greater than that of Mount St. Helens in 1980!

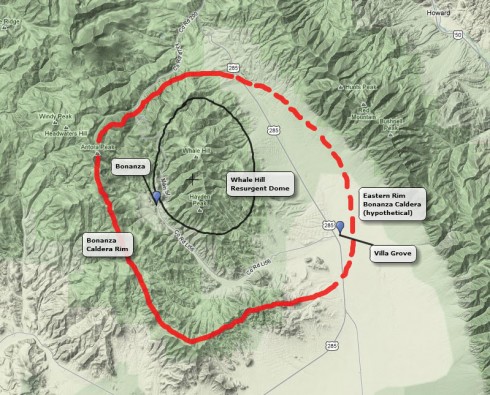

But there was more. Earlier researchers interpreted a fault system under the Kerber Creek as a “trap door.” Basically, they thought that as the volcano had erupted and emptied its magma chamber, one side of its floor – the Kerber Creek side – collapsed. Meanwhile, they said, the feature we know today as Whale Hill remained elevated. Whale Hill was the “hinge” on the “trap door” and was thought to mark the eastern rim of the volcano. The western rim ran from Flagstaff Peak to Sheep Mountain. It sounded “elementary.” But was it?

On a hunch, Peter studied the old lava flows that had filled the “trap door” structure and found they were angled as much as 80 degrees! “The lavas that fill the caldera are tilted, and that isn’t the way it’s supposed to work … things that fill holes should be flat. They couldn’t have solidified at such steep angles.” I imagined him quoting Sherlock: Once you eliminate the impossible, whatever remains, no matter how improbable, must be the truth.

Peter double-checked the rim structures, the valley fault lines, and the array of minerals present. And from all these factors, a new story began to emerge. Whale Hill had never defined the eastern rim of the Bonanza caldera; instead, it was the crest of an uplift – called a resurgent dome – at the center of a much larger volcano. The lavas were tilted because after filling the floor of the volcano and solidifying they were pushed up. It was, as Peter said, “like inflating a balloon beneath a sheet of paper.”

It was a huge breakthrough. Instead of a run-of-the-mill volcano five miles across, the Bonanza caldera had been at least three times that size, and its rim had once soared two miles above the caldera floor. (Crater Lake in Oregon is only about five miles in diameter and stands one-half mile from floor to rim.) One reason the Bonanza caldera had been so misleading is because the entire eastern third of the rim is now completely gone. It slumped and eroded away as the Sangre de Cristo Mountains began to rise 25 million years ago – about 10 million years after the eruption. Alpine glaciers acting over the last 100,000 years have dealt the most recent large-scale erosion.

This mystery may be solved and the perpetrator revealed, but there are still plenty of details left to wrap up. An aerial survey conducted in 2011 measured magnetic variations in the floor of the San Luis Valley. As the data is analyzed, this survey should help determine the shape of the vanished eastern portion of the caldera’s rim.

And if you happen to see a man in the mountains around Bonanza whose geology students are trying to keep up, it is likely Dr. Peter Lipman. He and his team of “Watsons” are continuing to track down clues to solving more riddles in the rocks.

Bill Hatcher is a local writer and an amateur geologist. Watch for Bill’s upcoming book, “The Marble Room: How I Lost God and Found Myself in Africa”, scheduled for release this November. (www.billhatcherbooks.com)

Thanks for this very interesting article!