By Glenda Lee Vollmecke

Outskirts Press

Paperback: 192 pages

ISBN-10: 1478712406

ISBN-13: 978-1478712404

Reviewed by Elliot Jackson

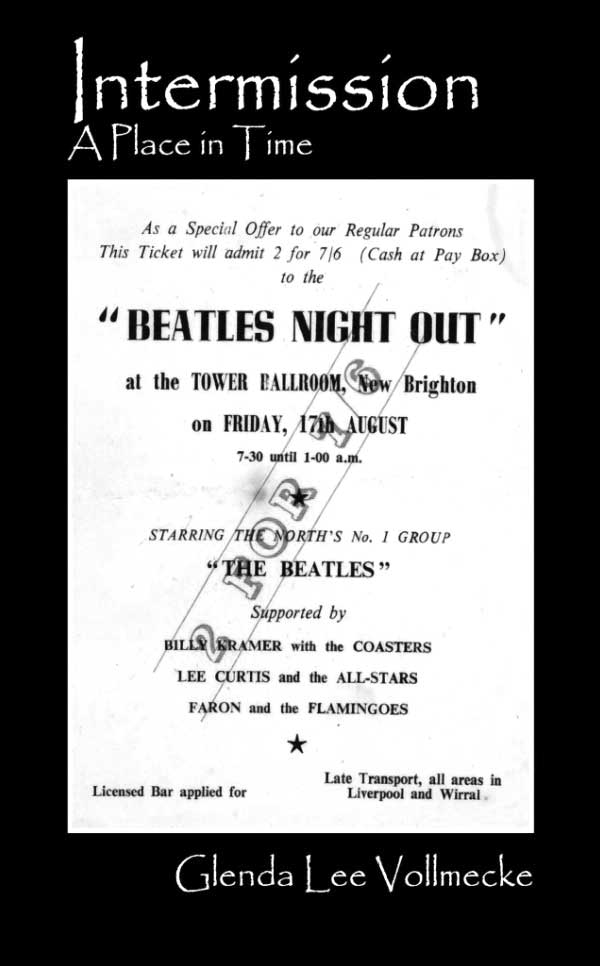

I confess, I started this book laboring under a misapprehension. From the cover art, which shows a handbill for a “Beatles Night Out” at “The Tower Ballroom, New Brighton,” I was expecting a lot more about the English music scene of the mid-1960s. Instead, this series of autobiographical vignettes, written by an Englishwoman currently living in the Sangres, features a discursive range of experiences from her early life – descriptions of eccentric relatives, of various locations in the British Isles where said relatives lived, ghost-hunting and bits of folklore, all mixed together in a way that suggests a series of paths meandering through a garden. As a result, I found it difficult to work straight through the book. If you’re not too fussed about where you’re going and what you’re seeing, however, you could just as easily skip around as read straight through, and this is what I did.

I confess, I started this book laboring under a misapprehension. From the cover art, which shows a handbill for a “Beatles Night Out” at “The Tower Ballroom, New Brighton,” I was expecting a lot more about the English music scene of the mid-1960s. Instead, this series of autobiographical vignettes, written by an Englishwoman currently living in the Sangres, features a discursive range of experiences from her early life – descriptions of eccentric relatives, of various locations in the British Isles where said relatives lived, ghost-hunting and bits of folklore, all mixed together in a way that suggests a series of paths meandering through a garden. As a result, I found it difficult to work straight through the book. If you’re not too fussed about where you’re going and what you’re seeing, however, you could just as easily skip around as read straight through, and this is what I did.

Toward the end, I did encounter the essay I was looking for: “Working at the Tower – The Beatles.” It describes the concert indicated on the cover, and certainly does contain a load of interesting and entertaining details. I had no idea, for example, of the mechanics of 60s-era blow-up falsies, let alone what an awkward business it is to set things to right if one or both of a girl’s mammary enhancements suddenly deflate on the dance floor. (This happens not to our narrator, I hasten to add, but to her friend.) Now, I am enlightened. There is also a strangely compelling portrait of Paul McCartney as a fed-up young Orpheus, angrily bidding a cluster of teenage Maenads in pink curlers to “get off my f–king leg” – this into a live microphone, as a bunch of industry suits are hovering and wincing in the background. A far cry indeed from the polished, smiling, unflappable image the future Lord Paul presents later in his career.

My biggest criticism of “Intermission” is that I found it overwritten, in a strangely ornate style bristling with dependent clauses that caused my attention to wander more than once. (This is a strange criticism from me, I know, who loves a good clause as much as anyone, and more than most.) I would love to see this book re-written in a more conversational style, because there are some real gems of anecdote and history buried in the verbiage. However, Reader, if you are possessed of more patience than I, and a genuine curiosity about working-class English life in the mid-20th century, you will doubtless find a great deal in this memoir to reward your attention.