ON FEBRUARY 1, 2003, KHEN 106.9 broadcast on-air for the first time. This moment represented years of hard work for volunteers of the Salida-based radio station. The task required both the construction of a physical space and the navigation of licensing logistics with the Federal Communications Commission. However, while KHEN might hold the honor of being the first legal community station in Salida, it was not truly the first. That distinction belongs to Free Range Radio. This pirate station, active circa 1997, operated out of a windowless room above First Street with a 1-watt transmitter and an antenna made of copper plumbing pipe.

Free Range Radio became a reality due to the efforts of the Salida Radio Club, which consisted of a few dozen people including Mark Minor and Jane Carpenter, who were both instrumental in getting the pirate station up and running. Jane volunteered at KGNU in Boulder in the mid ’80s and loved listener-driven radio. (When she moved to Salida in 1989, her only regret was that there was no community radio station.) She describes the SRC as, “A group of people who had migrated to Salida in the ’80s and ’90s and really loved the idea of community radio. It just sort of evolved.”

Minor brought a passion for subversive, underground radio and a frustration with the mainstream media’s lack of important content (even NPR, which he described as “the friendly part of the machine, but still the machine”). He became a fan of Free Radio Berkeley (FRB), headed by Stephen Dunnifer, a prominent member of the microbroadcasting movement. The FRB existed to subvert the corporate broadcasting model and encourage community members to create their own media content with low-level radio transmitters. Dunnifer sold low-cost transmitter kits to help small, unlicensed stations get up and running.

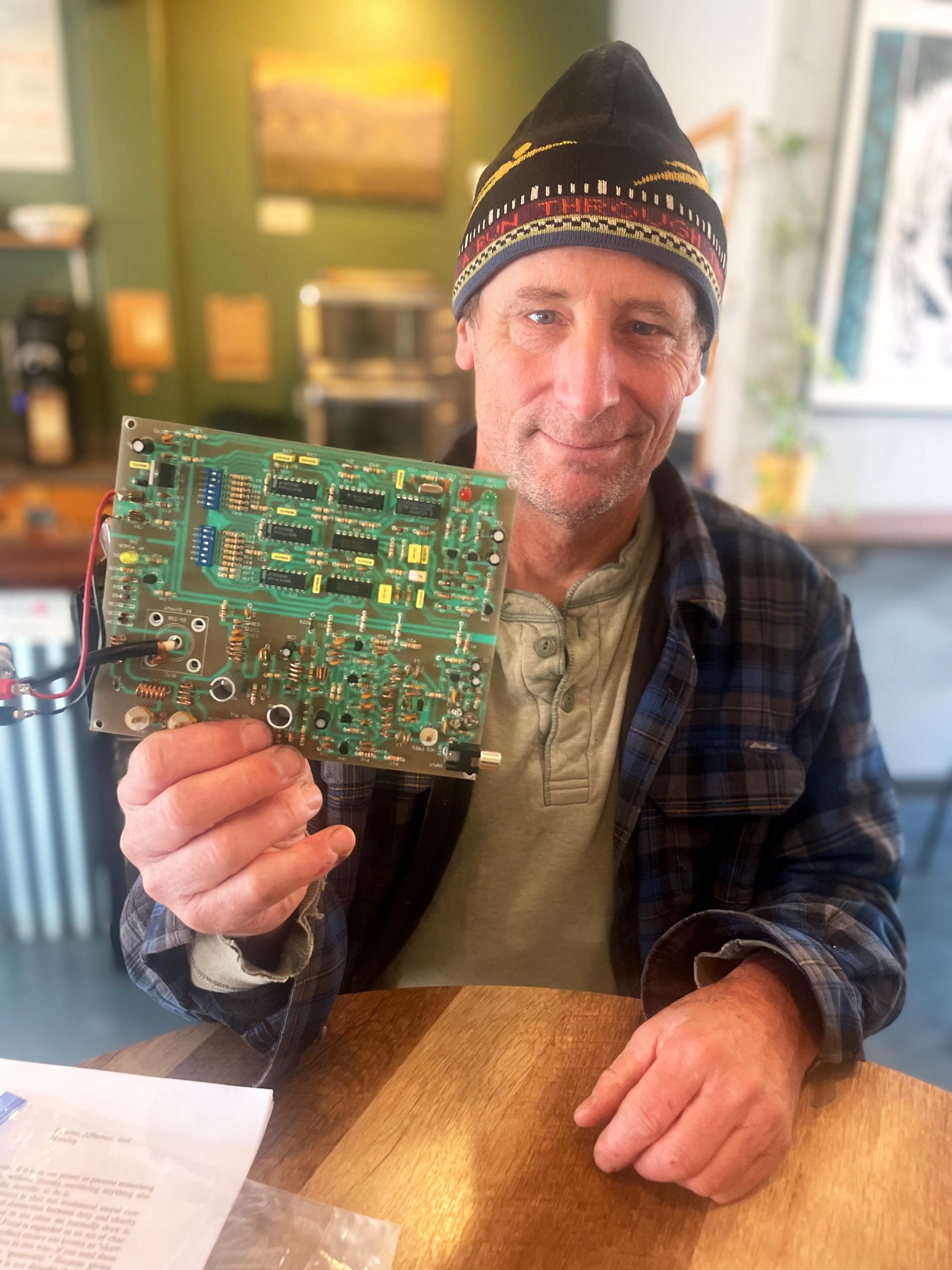

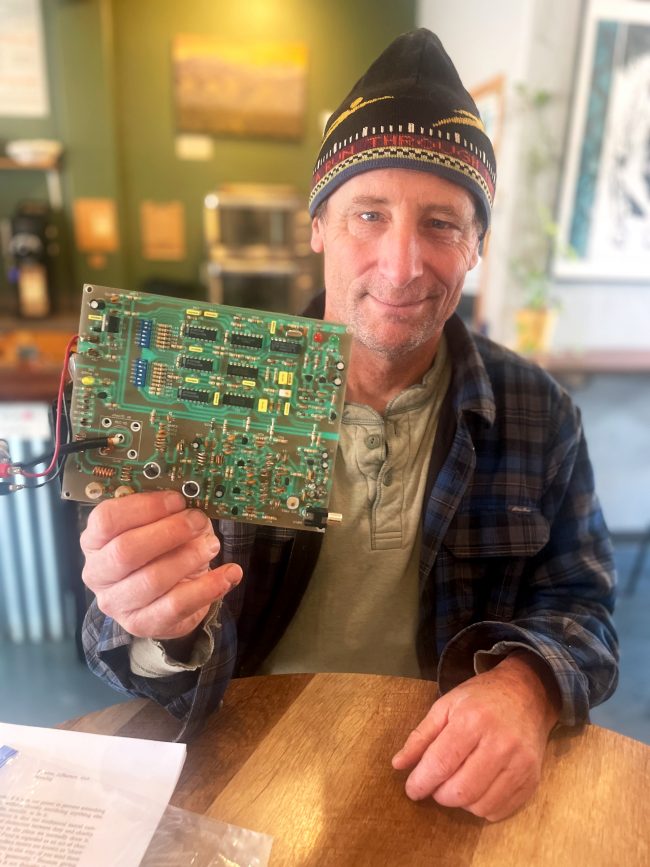

Minor purchased a kit and assembled it on his kitchen table. Free Range Radio was born. The transmitter, which he still has today, initially powered the station from his building on First Street. “If we had the zombie apocalypse, this could be the only thing you might have communication with. You hook this to a car battery and you’ve got a radio station.”

According to Carpenter, the initial signal didn’t reach very far past downtown; but eventually the station upgraded to a 6-watt transmitter. Technically, 6-watt transmitters shouldn’t send a signal outside city limits. But Minor recalled getting calls from prisoners in Buena Vista, saying they could listen in their cells.

Once the signal started transmitting, Free Range Radio was there for the community. “We were not secretive about it,” Minor said. “It was out in public.” The station posted a schedule listing shows and times; and for the most part, DJs adhered to FCC guidelines. Although Minor recalled scolding the late-night high school DJs for “a five-minute string of F-bombs,” he also said they knew where to hold the line.“We were trying to conform to what we thought was a community standard. We wanted, like, an old lady to be able to listen to it and not be turned off.”

The content on Free Range Radio varied from show to show. Minor described the intention as “community media activism … not entertainment.” In his estimation, “It was political. It was super organizing and grassroots and communication. That was our motivation.” On his show he sometimes played prerecorded, independently produced news segments from groups like the Micro Radio Network, who were looking to transform the media landscape.

Carpenter said she cared most about how radio could support the community. “For me, it was about giving voice to the people. … We were portraying a different view of America. We didn’t have access to the internet but anybody could go to Caring and Sharing and buy a radio for $1 and listen to a station that had all kinds of information that wasn’t controlled by corporate media.”

In Carpenter’s estimation, the content on Free Range Radio varied from person to person. Her show, Radio Wrangling, featured cowboy songs she thought might appeal to the local ranching community. Others would report on the weather, she said, or play their favorite songs. On an unscheduled segment called the Dumpster Report, people regularly called to let listeners know “if they heard of a good score in a dumpster somewhere.”

However, despite the on-air adherence to FCC guidelines and the community-minded intentions of Free Range Radio, the station was still illegal. “Pirate had a shelf life,” Minor said. “It would get shut down. It was not sustainable.” He remembered a visit from an older guy in a collared shirt who seemed a little too square and a little too curious. While it was never confirmed, Mark suspected the visitor was from the FCC.

Carpenter recalled that, as more unlicensed radio stations popped up around the country, more stories of raids started circulating, too. “When you have multiple pirate stations across the nation being busted down with law enforcement carrying guns and throwing people in jail, we had every right to be paranoid. And the more those stories came out, the less people wanted to continue the Salida Radio Club. We just decided to shut it down.” About a year after it began, Free Range Radio was off the air.

But the story doesn’t end there. Carpenter said, “The Salida Radio Club may have decided to stop broadcasting, but there was still that core group of people who wanted community radio. It was a dream.” Carpenter stressed the importance of keeping Free Range Radio separate from the legal entity that eventually became KHEN. But the experience of running a grassroots station planted the seeds for the dream.

When word started traveling through the grassroots radio community that the FCC would open a window of opportunity for low-powered licenses, the dream endured: the Salida Radio Club was ready to go legit. But that’s a story for another day.

To be continued … ?

Lisa Ledwith has always been a radio child. She lives and loves in Salida.