Article by Columbine Quillen

Pack-burro racing – January 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

IT’S A SHORT SEASON for a professional donkey racer; the pack burro racing season is not nearly as long as the football, basketball, or hockey seasons. And the profession is not nearly as prestigious — nor as lucrative. But to keep winning the ultimate prize in pack burro racing, as Barb Dolan has, you have to train all year. Winter is not an excuse to hang out and watch television for nine months.

Pack burro racing is the only sport indigenous to Central Colorado, and it’s not a game for the weak. It involves running alongside a donkey — which is exactly the same thing as a burro, burro being the Spanish word for donkey — on steep mountain passes and narrow desert trails. The donkey must carry 33 pounds of gear which includes a pick, a shovel, and a gold pan.

The races are long and steep over rocky and exposed terrain, and frequently the donkey decides that it would just as soon not go the distance. But the runner must stay alongside his or her animal for the entire race — often coaxing it in directions it doesn’t want to go, or urging it back on course from directions it prefers. Cajoling the donkey is often a bigger challenge than the actual run.

There are various burro races every summer; and some of them are a mere five or six miles long. But there is a competition amongst the burro racers to see who is the strongest, and it’s called the Triple Crown.

The Triple Crown is composed of three races, a 21-mile race in Leadville, a 29-mile race in Fairplay, and an eleven-mile race in Buena Vista. The winner of the Triple Crown must win all three races with the same donkey, and the races often take place on consecutive weekends — so there’s not a lot of time for recovery.

I’ve run a few pack burro races, and I can assure you that it looks a lot easier than it is. If you’ve ever seen the beginning of a race with twenty donkeys all kicking, braying, and bucking, you can only imagine how out of control the runner can feel. It seems to me that whenever I feel strong and fast, my donkey doesn’t want to move. There’s a reason they’re called stubborn: if a donkey really doesn’t want to move, he isn’t going to.

But on the other hand, when you’re feeling weak and tired and in need of a break, the ornery beast generally wants to cruise along at warp speed. I have rarely run a race where I didn’t come to a point where I just wanted to leave that darned donkey there and never see one of those creatures again. Burro racing is one of the most frustrating things I’ve ever done.

Yet I was always rewarded with the knowledge that I was part of an elite circle — although perhaps that’s because most people are smart enough to know better. Nevertheless, pack-burro racing gives determined runners and athletes — who aren’t seven feet tall and can’t throw a ball more than a hundred miles an hour — a chance to be a professional sports star every once in a while.

BARB DOLAN, however, proves to be a star at every race. She has always been athletic, which is what you might expect from someone born and raised in Boulder, Colorado. Barb has a twin sister, Nancy, and they were competitive swimmers from the time they were eight years old until they were in college.

As they got older, they got more into road bike racing and started racing nationally on sponsored teams. Then Barb started to bike less and run more, and she got interested in trail running.

When Barb met a friend in Leadville who was a pack-burro racer, she was intrigued. “I’m game,” she said. And the rest is just a story about a fast woman and a donkey.

In 1990, Barb ran her first burro race in Fairplay. At the time, the long course was called the men’s race, and the short course, the women’s race. But after that, Barb seldom ran the short course again, because to win the Triple Crown she had to run the long course. But she hated running with a burro. “After the race I swore that I’d never do that again.”

Before long, Barb decided to leave Boulder county. “I had been a dental hygienist in the Longmont area for almost ten years and wanted a change.” She worked in the service industry in Vail and Beaver Creek for six months after leaving the Front Range. But she wasn’t making enough money so she decided to go back to being a dental hygienist.

Barb knew some burro racers in Leadville, and that helped her decide to look for a place down valley. For a year, she worked for Dr. Steinauer, a Buena Vista dentist, and then she started working at the prison, where she still works.

She had made a commitment to a location, but making a commitment to pack-burro racing wasn’t as easy. “That first race was the worst. It was the hardest thing I’d ever done. I didn’t know how to handle the animal, and it ran so fast I could barely hold on.”

At her first race, Barb kept calling out to Mary Walter for advice, and Mary told her how to place the rope to have more control. Still, Barb claims that she was holding on for dear life. “I got so sick that race. I didn’t drink any water.”

Barb came in fourth or fifth, but she didn’t give up — even though, immediately after the race, she swore she would never do it again. “But as much as I hated that first race, I had to figure it out. It was challenging in that respect.”

The next year, Barb ran every race. She still didn’t own a donkey, however, and was using a friend’s. She ran with that donkey for a couple of years and then bought Sailor in 1994 or ’95 from her friend Diana Makris.

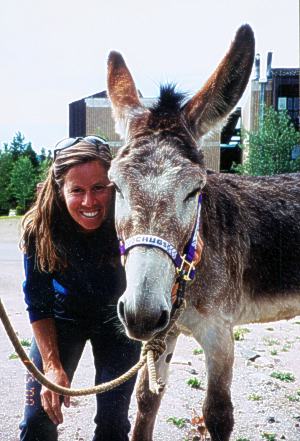

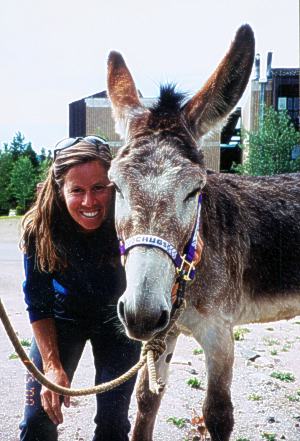

Makris had been racing with Sailor for years but had decided to get out of burro racing, so she sold him to Barb, and Barb still has Sailor, who is easily recognizable because he has an anchor-shaped “tattoo” bleached out on his neck.

Today, Barb keeps racing, even though it hasn’t necessarily gotten any easier. One year, she and her donkey got stuck in the snow on Mosquito Pass. As she came up the hill, her donkey started to sink into the snow until it was mired up to its chest. Jim Feistner was running next to her and his donkey got stuck too. Fortunately, a friend, Ralph Herzog, was nearby and had a decent shovel. Barb and Jim spent the next hour or so digging out the two donkeys.

“It was actually really scary. We had to dig out twenty feet or more. It was a long race.”

ANOTHER TIME, Barb was running up Fifth Street in Leadville with Mary Walter when lightning began to strike. “I am deathly afraid of lightning, and we had to crouch down and try to run. That was really scary.”

After a few years, Barb got a new racing partner named Chugs. At first, Chugs was not such a desirable racing mate. “Sailor was so well trained. When I got Chugs I would be in the trees more than anything. We’d be running right on track and then BOOM, he would take me through who knows where, and then we’d be back on path and then BOOM, we’d be in the trees again.”

Barb says that things have changed in her years of pack burro racing. “When I first started, most races were separated by men and women. Mary, Kendra, and I would all run with each other. If one of us had to stop, we would all stop and wait for one another. The men, however, were all business.”

When Barb started running with the men, she became all business too. In fact, Barb’s best race happened in Buena Vista, and she was able to pass all of the men to win first place overall.

“I had a really good race. I was running with Curtis and then with Hal. I knew I wanted to stay close to Hal, who was really pushing it. At the bridge, Hal’s donkey stopped and I went right around him.”

Right now Barb and her husband, Don Mann, who is also a pack-burro racer, have four burros. They still have Sailor, although Barb now runs with Chugs, and she also owns Samaritan, and Ralph, a mammoth Jack. (Barb doesn’t race Ralph because she feels he’s too big and strong to control, but he is ridable.)

“Donkeys don’t really involve a lot of maintenance, but if you have them, it is important to run them and work them.” Barb doesn’t spend as much time with them in the winter, though. “They probably need a break too.”

Four donkeys is a lot and Barb says it’s hard to find time for the four of them, but fortunately, she has her husband and her sister (who also races) to help her.

Barb is extremely modest about her speed, strength, and awards. She doesn’t even know how many times she’s won the Triple Crown. “I think it’s six or seven years.”

She also does a lot of work to ensure that races take place and that the sport stays alive. For a couple of years there was no race in Buena Vista, and thus there wasn’t a Triple Crown. But in 1996, Barb, with the help of Sean Herrin, brought the race back.

I assume that Barb will be crossing that finish line ahead of the pack for years to come, which — despite her modesty — means that she must have figured it out.

Columbine Quillen, who keeps getting drawn back to Salida, has lost to Barbara Dolan in several pack-burro races.