By Ed Quillen

Names on our Land

Place names have long fascinated me, and perhaps for that reason, I try to use the right ones, and it grates on me when I hear the wrong name.

For instance, the eminence at the end of F Street across the river from Salida is Tenderfoot Hill, according to the U.S. Geological Survey, which is pretty much the authority on these matters, although for reasons I will explain later, I don’t go by the U.S.G.S. in all matters. The hill with the big letter and the gazebo on top is not “Mt. Tenderfoot,” and I fight the urge to start shouting about ignorance when someone calls it “S Mountain.”

That said, I’ve never been able to find out when it got its name, or why. In the West, a tenderfoot is someone inexperienced, perhaps a newcomer. The term may come from cattle drovers, as cattle not accustomed to being trailed, especially over rough ground, have tender feet which get sore quickly. Or so I’ve heard. I have trailed cattle, but when you’re a kid riding drag, you don’t worry so much about heifer hooves as you do about keeping the bandanna over your nose and mouth so you don’t inhale so much dust.

Tenderfoot Hill is almost barren of trees now, but in pictures from a century or so ago, it boasted quite a few piñons and junipers. One local legend has it that fumes from the smelter, whose stack remains on the edge of town, killed the trees. But it seems more likely that the trees succumbed to economically challenged locals during hard winters when they couldn’t steal enough coal from the railroad.

Anyway, it’s Tenderfoot Hill. And the street that crosses F Street at that end of town is not Sackett Street. It’s Sackett Avenue, named for an early land developer, for my 1885 house sits in “Sackett’s Addition to Salida.” That’s about all I know of Sackett.

That street used to be Front Street (the bordellos and saloons were called “the Front Street Resort District” in The Mountain Mail of yore, and I once spent a couple of days trying to figure out when the name officially changed. At one point in the early 1950s, it changed names at the intersection with F, from West Front Street to East Sackett Avenue.

But search as I might in various records and maps, I couldn’t find anything official. I know that many municipalities changed the names of their tenderloin streets after various reforms. That is, Holladay Street in Denver became Market Street, and State Street in Leadville became Second Street. And as far as I can tell, nearby Stillborn Alley and Hop Alley appear on no modern Leadville street map.

So I suspect that about the time that Laura Evans’s whorehouse was closed in 1951 – she put up a sign that said “No more girls” – the city decided to change the name of her street. But if it was done officially I haven’t found a record of it.

And every once in a while you hear that Salida itself was named after two working girls, Sally and Ida. Few place names are as well documented as Salida’s; it was christened in the summer of 1880 by Alexander Cameron Hunt, a former territorial governor who ran the railroad’s land-development subsidiary, the Central Colorado Improvement Co. Hunt liked Spanish place names, for he also named Alamosa (cottonwoods) and Durango (a Basque place name in Spain and then Mexico).

Hunt romanticized things a little when he said Salida meant “gateway,” when most dictionaries say it means “exit.” At any rate, it’s a Spanish word in good standing, and it doesn’t come from any of the “brides of the multitude” who once worked in that end of town.

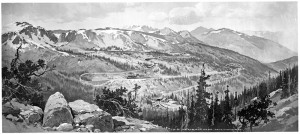

To move on with my place-name nitpicking, I cringe whenever I hear “Collegiate Range.” As far as I’m concerned, the correct locution is “Collegiate Peaks” or “Collegiate Peaks in the Sawatch Range.”

An 1869 surveying expedition from an Ivy League school gave us Mt. Harvard and Mt. Yale. Princeton, Oxford and Columbia came along later. But they’re a cluster of peaks inside a range, distinguished only by their names. They’re not a geological formation like a mountain range.

And besides, where do we draw the line on “Collegiate Peaks?” There’s a Sewanee Peak behind Mt. Shavano. There’s a Mount of the Holy Cross and a Holy Cross College, so is it a collegiate peak? You could ask the same question about Missouri Mountain and the University of Missouri. Or Mt. Belford and Belford University, an unaccredited mail-order operation that even offers doctoral degrees.

Granted, it can be difficult to say where a mountain range starts and ends. Consider the south end of the Sawatch Range (a simplified spelling of Saguache, which it is on some old maps). Mt. Shavano is the last 14er. South of that is Ouray, at 13,976, and certainly part of the Sawatch Range. The next real peak to the south is Antora (not Antero which sits north of Shavano). It’s only 13,269. Maye it’s the south end of the Sawatch Range. Or perhaps it’s the start of the La Garita Hills that eventually become the San Juan Range. Such boundaries aren’t all that definite.

For instance, when I first lived in Salida I learned that the low mountains across the river were called the Arkansas Hills or less formally, the Ark Hills. But for a while I worked with a guy who grew up here, and he called them part of the Mosquito Range. To me, the Mosquito Range started at Fremont Pass and ended at Trout Creek Pass, whence began the Arkansas Hills that extended to the Arkansas River after it turned east near Salida.

Who was right about the proper name for this range? You could doubtless find a reference to support either view. But I’ll keep the Mosquito Range north of Trout Creek Pass. As for how a mountain range got named for an insect, the story goes that the pioneer miners held a meeting to name their mining district in the Fairplay area. The meeting adjourned without agreement, but when they opened the record book at the next meeting, a mosquito was squashed on that page. They took it as a sign and so christened the mining district, which gave its name to the pass and the mountain range.

As for other place names hereabouts, I sometimes wish our pioneers had been a little bit more creative. Salida’s downtown grid with its numbered and lettered streets is relatively easy to navigate, but pretty boring. And you’ve got to remember that the East and West are not compass directions, but railroad East (toward Cañon City) and West (toward Leadville). In days of yore, the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad had milepost 0 in Denver. If the milepost numbers increased as the train progressed, it was a westbound and a decrease made it eastbound. Like most railroads, it didn’t bother with northbound or southbound.

Anyway, these non-creative place names extended to certain waterways, as in “Middle Fork of the South Arkansas River.” The South Arkansas was christened the Rio San Augustin by Juan Bautista de Anza in 1779, and I wish that name had stuck. But locals often call it the Little River, a name I like even though the U.S.G.S. does not list it, and one developer made it into some Real Estate Spanish (the leading commercial dialect of the American Southwest according to New Mexico writer Stanley Crawford) with a Rio Poco subdivision.

Another place where I part company with the U.S.G.S. is on apostrophes. Before we go there, I’ll note that the U.S.G.S. does not have any legal authority to enforce place names. All it does is decide what will be used on federal maps and other publications. We’re free to use the traditional “Son of a Bitch Hill” for a grade west of Gunnison, rather than the civilized “Blue Mesa Summit.”

The U.S. Board on Geographic Names, a part of the U.S.G.S., forbids genitive (possessive for you non English majors) apostrophes in natural place names, with five exceptions, among them Martha’s Vineyard in Massachusetts.

That’s why the map shows “Pikes Peak” when English grammar and orthography say it should be “Pike’s Peak,” a locution I tried to use when we had this magazine. Or Brown’s Cañon instead of the federal mapmakers’ Browns Canyon.

And let us not forget that we’re Coloradans, not Coloradoans. The rule is simple. If a place name ends in “o,” add “an” – except if it’s Spanish, in which case you drop the “o” before adding “an.” Idaho and Chicago are not Spanish words, so you get Idahoan and Chicagoan. Mexico and San Francisco are Spanish, thus Mexican and San Franciscan. Since Colorado is a Spanish word, Coloradan is the proper term.

Someday, perhaps, I’ll compile the Grumpy Old Natives Guide to Colorado Place names. If nothing else, it should be better at starting arguments than settling them.

Ed Quillen lives and works in what he calls Central Colorado, even though the Colorado Division of Wildlife makes Central Colorado the greater Denver area, which is nowhere near the center of the state.