What prompted you to begin writing poetry?

What prompted you to begin writing poetry?

A mother thwarted in her dream of becoming a surgeon because, although she got accepted into an accelerated high school program in San Francisco in the ‘30s, her alcoholic father beat her if he found her reading or doing homework at home. Running away at 16, she met my handsome Italian dad and became a mother of three sons. Collecting and reading books was a hobby of hers, and I developed a love of reading, spending a lot of time at the local library. I actually was guilty of sometimes reading page after page of encyclopedia entries while my brothers played neighborhood games outside.

That love of language and curiosity for knowledge served me when, at the age of 14, I entered St. Joseph’s Roman Catholic Seminary (retiring Supreme Court Justice Greg Hobbs was a classmate). As a boarding school student, I began writing weekly letters home. Some morphed into verse – admittedly of the most derivative sort. By second high (my sophomore year), I had written my first real poem – paralleling a river from headwaters to mouth with the lifespan of a person. The following year (1963), a local newspaper featured my first published poem, decrying the scenic blight of recently erected “Power Towers.” I’ve been addicted to the lyric valuables ever since.

How did you become poet laureate of the Telluride Mushroom Festival? Is this a competitive position?

In 1989 I won a $4,000 creative writing fellowship in poetry from the Colorado Council on the Arts & Humanities, along with my friend Karen Chamberlain. Up to that time I’d been the Mushroom Festival’s local director of operations. But I asked that my title be poet-in-residence instead of director, which for 15 more years was my primary function – although for 25 years I did bring an arts component to what was essentially a science event, with annual performances I did or directed.

While that was self-anointed, rather than competitive, I did receive the competitive title of the first Poet Laureate of the Western Slope (PLWS) at the Karen Chamberlain Poetry Festival in Carbondale in 2011. Aaron Abeyta of Antonito served in that position from 2013 to 2015. Rosemerry Wahtola Trommer of Placerville is the current PLWS.

Having been born in San Francisco, were you influenced by the Beat poets such as Lawrence Ferlighetti and Alan Ginsberg? Who are the poets who have influenced you most?

Did I drink my mother’s milk? I came of age in the San Francisco Renaissance. Kenneth Rexroth, Jack Spicer, Lenore Kandel, Lew Welch. Living as a youngster in the suburbs south of the city, I knew about the Bohemians before the Beats took over North Beach and San Francisco Chronicle columnist Herb Caen invented the term “beatniks,” which is what I was called working as a Vista volunteer on a reservation in Montana in the mid-Sixties. But while I read the Beats, heard them read and hung out some with North Beach legend Jack Mueller (who now lives as a hermit in Log Hill Village outside Ridgway), I was more associated with SF street poetry, a legendary poet center called Cloud House, and a gang of artist provocateurs called the Union of Street Poets.

I first read Gary Snyder’s Riprap in 1969, and I was entranced. He was the poet I most admired, living on San Juan Ridge in California’s Mother Lode foothills. His voice resonated best with the ecological and anthropological slants of my own poetics. I drank wine with Gary and heard him read for the first of many times at a bioregional movement conference organized by Peter Berg and the Planet Drum Foundation in the mid-‘70s.

Lew Welch and Snyder had been classmates at Reed College in Portland. For a beginning poet, I felt Snyder’s mythic scan and intellectual rigor complemented Welch’s masterful American language and rhythms. I heard Welch read just once – one of the treasures of my life – a year before he disappeared into the Sierra Nevadas, never to be seen again. Currently I’m a member of a group of Colorado poets loyal to Welch and his American poetic style – the Fire Gigglers. Of course I admired and appreciated Ferlinghetti and Ginsberg as public poets, although my personal exchanges with them were, in fact, actually unpleasant.

In San Francisco, Kush, the crazy Bard College poet archivist and founder of Cloud House, was one of my greatest influences: expanding my mind to encompass the broadest reach of poetry’s grand diversities – from Lautremont and Whitman through Dickinson and Li Bo to Neruda and Ernesto Sandoval; teaching me to listen to others, whether homeless sadhus or Black College masters, unmediated heartsong or polished diamond; believing poetry should be made by all, his motto was, “Poetry is the Heart at Liberty.”

[InContentAdTwo]

Could you tell us a bit about Talking Gourds?

The perfect segue, as my next biggest influence wasn’t a poet at all. Moving to Colorado, I become poetry editor of Earth First! Journal in 1981. And in 1989, I met Dolores LaChapelle at an Earth First! Rendezvous I helped organize on the Uncompahgre Plateau. It was intellectual love at first sight. Dolores was a deep ecologist, tai chi teacher, mountain climber with several first ascents in Canada, expert powder skier, and director of the Way of the Mountain Center in Silverton (CO). Already a crone, she became my mentor and friend. Through books and around campfires, she taught me that the role of bardic poet is a sacred path. That speaking for one’s place and for all the human and more-than-human living beings in that place was one of the essential ways to return to a Paleolithic understanding of the interconnectivity of the natural world – a perspective we’d lost in our modern allegiance to Industrial Growth Society.

In LaChapelle’s magnum opus, Sacred Land Sacred Sex Rapture of the Deep: Concerning Deep Ecology and Celebrating Life, she also talked of the power of the talking stick circle, like we used to make decisions at the hippie Rainbow Gatherings I attended many times. Also, the power of the gourd as symbol and sacred object (Jerome Rothenberg’s ethnopoetics anthology, Shaking the Pumpkin). Combined with my dislike of sign-up lists, microphones and stages to showcase the sharing of poems and the lesson I’d learned at Cloud House of listening to others as well as performing for them, I dreamed up the Talking Gourds circle – which became the core of an ever-shifting annual poetry gathering. Passing a “partnership” gourd instead of a “phallic” stick around the circle, my poet friends Judyth Hill, Joan Logghe, Mike Adams and I developed (with others) the practice of reading poems to one another in a safe, egalitarian environment, where the holder of the gourd has the floor and everyone else listens. That practice has been used at various poetry gatherings around the region and adapted beyond poetry as a wrap-up for the annual Headwaters Conference in Gunnison. A Talking Gourds program with three branches – annual event, monthly readings and a western states poetry prize – continues in Telluride under the aegis of the nonprofit Telluride Institute.

What about your involvement with Jack Mueller’s Union of Street Poets gang.

I love ideas. Not so much programmatic planning, but rather the serendipity of breakthrough concepts that one can play with and experiment at manifesting in the world we find ourselves in. In ‘60s San Fran, the entire culture was up for grabs. Cheap copying had just arrived, replacing the messy mimeograph machines of the ‘50s. Hardback publishing seemed so old-school – fraught with money and class issues. Inbred and expensive. So Jack decided to bypass all that. He encouraged us to duplicate a couple hundred copies of one of our poems and paste them up around town – in laundromats, on buses, at public parks and all over our neighborhoods. Many of us did, signing them with the “Union of Street Poets” hashtag. They were essentially free broadsides. They livened up the local street scene in the city. Made for lots of surprise epiphanal moments. I still give away free broadsides under the banner of the Union of Street Poets, Vincent St. John Local, Kuksu Brigade (Ret.).

Are you still the poetry editor for Fungi magazine out of Wisconsin? What does that entail?

Yes, I enjoy selecting poems I like from fellow poets and sharing them in nontraditional, non-literary-only magazines. I did that as poetry editor of Earth First! Journal (1981-91), Sustainable Mountain Agricultural Alliance’s Small Talk (1989-1990), Wild Earth (1992-2000), and Fungi currently.

For the last 30 years, as a weekly op-ed columnist for various Telluride newspapers (and for the last dozen years a monthly columnist in the San Juan Free Press out of Cortez), I’ve included a Talking Gourd poem at the end of all my columns, sometimes one of mine, often of others.

I’m also poetry coeditor of an online poetry litzine, Sage Green Journal, with my friend Lito Tejada-Flores, who lives half the year in Crestone and the other half in southern Chile.

Since I buy a lot of poetry books and read a lot of poetry, I enjoy finding poets whose work I like and inviting them to submit their poems for publishing.

You are currently serving your fifth term on the San Miguel County Board of Commissioners. What prompted you to run for office in the first place?

I’d long been active in environmental issues, politics and social causes, both in California and Colorado – perhaps springing from my idealism as a youth and the kind of messianic do-gooder complex that goes with entering a seminary. In Telluride, I covered local politics, particularly county government, for several local newspapers as reporter and editor. It was perhaps the best apprenticeship one could ask for in uncovering the local political scene and its power structure.

When a spot opened up in my district (in Colorado you have to live in one of three districts in a county, so as to get geographic representation, but you are elected countywide, so as to reflect in policy the wishes of all the county’s residents), I stepped up to run and won against a fourth-generation rancher whose grandpa had served in the legislature. After cofounding Telluride’s environmental group, Sheep Mountain Alliance, and shepherding an advisory San Miguel County Logging Task Force through two years of meetings, political office seemed the next best step to effect local change.

You were first elected as a Democrat and then you switched to the Green Party. Why the change?

Ouch! It’s a sad tale.

By the time I moved to San Miguel County in 1980, it had become a Dem stronghold, which matched my progressive bent. I served as a county Dem party treasurer, was active as a Dem precinct lieutenant and even went as a Dem county delegate to the state convention one year.

But by 1998, I looked around at the Dems and this is what I saw: Pres. Clinton caught in a baldface lie (I didn’t care what he did or didn’t do with Monica, but lying about it – in many countries he would have been expected to resign, which could have put Gore in office, and the lesser Bush might never have been elected, and there would have been no Iraq War, etc., etc.).

On the state level, I watched as National Dem Party Committee Chair Roy Romer, the former Colorado governor, refused to campaign for his lieutenant governor, Gail Schoettler, in her run for his seat when he left office, allowing Republican nightmare Bill Owens in by the narrowest of margins – which led eventually to the killing of state funding for the arts, the messing up of the human resources computer system to the tune of millions of dollars, and generally sending the Centennial State back into the Reaganomic dark ages.

Finally, on the local level, I saw rich, behind-the-scenes Dem party brokers elect a felon, convicted of child abuse, to the county Dem committee in order to have enough votes to get rid of a black chair – because she wouldn’t toe their political line.

Quite frankly, I was fed up with Dem shenanigans on the local, state and national levels. Luckily, a couple Dem legislators got Colorado to institute a simple “minor party” ballot status process in 1998, in hopes of encouraging Libertarian votes away from the Republicans. But it also empowered the left-leaning Greens. So I switched parties midway through my first term. And truthfully the Green Party’s 10 Key Values more closely conformed to my own progressive beliefs than much of the Dem platform. Changing parties has allowed me to run four times after winning a Green Party state convention vote, instead of having to run in a Dem primary. And my name then has appeared on each ballot as a Green Party candidate, alongside the Dem and Repub candidates for San Miguel County Commissioner.

As co-chair of the Green Party in Colorado, and the only elected Green Party candidate in the West, what do you see for the future of the party?

Actually, I’m not currently co-chair, although I served in that capacity for several years. I was also chair of a national Green Party committee for a couple years, and gave the invocation at the beginning of the national party’s first national convention in Denver, 2000.

And there are literally dozens of elected Green Party officials in the West, with California having at least one mayor, a commissioner, several council members, and a scattering of others elected in several other Western states. However, only a handful of those have won in partisan elections (most municipal elections are nonpartisan, where one’s party isn’t listed on the ballot). And while I have worked at the National Association of Counties in D.C. with a couple Green commissioners from Minnesota, I believe I am the only county commissioner and partisan-elected Green in the interbasin West. Or have been in the past. The national party doesn’t communicate with its elected leaders very well (if at all).

Which is to say, the Green Party has more or less followed the century-old script for minor parties in the U.S., running celebrity candidates or party operatives at the state and national levels without any chance of winning. I believe it tags us as a party of losers. I have long been an advocate for “building the party from the bottom up” – following one of our key party values: grassroots democracy.

I believe the party ought to be running candidates for local offices, school boards, etc.; and we should not run candidates for higher offices until we have built up a core of viable candidates who can realistically compete with better-financed major party folks. And our party ought to be recruiting proven community leaders with strong local issues under our ballot line – not letting party members run “educational” campaigns that embarrass as much as educate. With those strategies, given the difficulty of our minor party status in the American political system, we might have a future. Certainly with over 70 Green Parties worldwide, the Green Party movement internationally will be a wave of the future, although our deeply flawed political system in this country will likely retard American Green Party development for some time.

What is your biggest current concern as a representative?

While not a state or national “representative” but a county commissioner, I do represent my local constituents – the majority of the 3,000 voters who elected me and the 7,500 residents of the county. Our biggest interconnected issues are representative of most counties dominated by industrial tourism – income inequity, ecological preservation, insufficient pay for workers, affordable housing, public transportation, controlling growth, promoting economic development (yes, those last two are antithetical, which is part of the reason politics is so tricky), and four personal projects I’m most excited about: trying to develop a Carbon Ranching payment for ecosystem services (PES) program for our ranch community, along with help from the Quivira Coalition in New Mexico; apologizing to the Uncompahgre Utes for their forced, illegal and scandalous removal from San Miguel County in an effort to begin a process of reconciliation (which has never happened before) and trying to figure out appropriate acts of atonement for that injustice 135 years after the fact; working with state and local officials to turn the west end of San Miguel and Montrose Counties into meccas for a burgeoning recreational bicycling industry; and finally seeing hemp ranching develop and thrive in San Miguel County.

You serve on many bodies, including the Colorado Rural Development Council, Western Colorado Congress, the Public Land Partnership and the Forest Service’s Healthy Forest Partnership, among others. How do you find time to write and perform poetry as well as maintain your hobby of hemp basket weaving?

Well, I’ve served on over 50 boards and commissions over the past 20 years in office. Currently I’m on the executive committee of the Telluride Institute, the Public Lands Partnership (Montrose), various Colorado Counties Inc. committees, local cross-jurisdictional groups like the Intergovernmental Committee, and many adhoc groups, like the West End Bicycle Alliance and the Telluride Literary Arts Festival.

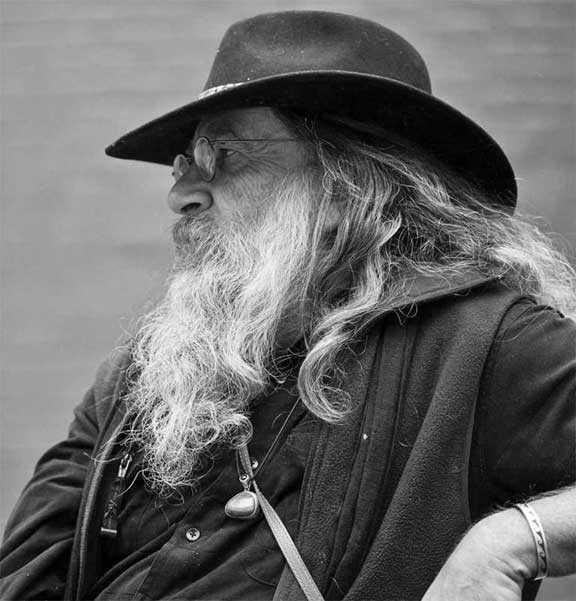

My wife died several years ago, so I single-parent a wonderful young man of 16, in addition to growing 25-plus varieties of organic heirloom potatoes, as well as giving and hosting poetry readings, writing weekly and monthly op-ed columns, and participating in all my political meetings. Even at 70 there still seems to be some energy left in the old ticker. It’s probably because I love working for the people rather than having to work for some corporation.

I learned to weave baskets from a Pomo healer in California, Mabel McKay, and I take advantage of beaucoup sitting time at meetings to keep my hands active as I listen.

I have used hemp twine for my baskets, my versions of which I refer to as “wall mandalas,” since they are intended for their swirling display of colors more than any utilitarian function. Mostly I use cotton yarn found in a variety of places and among any number of styles – although hand-dyed Churro yarn from Tierra Wools in Los Osos, New Mexico, is perhaps my favorite.

You’ve described yourself as a “paleohippie.” Could you define paleohippie?

Someone who’s twice the age of anyone you should trust.

Is Goodtimes an Italian name?

It’s a translation of my Italian patronymic – Bontempi.

Any upcoming events we should know about?

For Central Colorado, the annual Headwaters Conference at Western State Colorado University in Gunnison happens Sept. 18-20. I’ve attended 25 out of 26 years. It’s a never miss, if I can help it. This year’s theme: The Art of Community: Creative Place-Making in the Headwaters.