By Mike Rosso

During World War II – from 1943 to 1946 – Colorado was home to around 43 Prisoner of War (POW) Camps, according to Metropolitan State University of Denver. Nationwide, there were 175 Branch Camps serving 511 Area Camps housing nearly 425,000 POWs, most of whom were German, although some of the earliest prisoners were Italians captured in North Africa. The camps were administered by the United States Army Provost Marshal General’s Office and the Colorado region was administered by the Seventh Service Command.

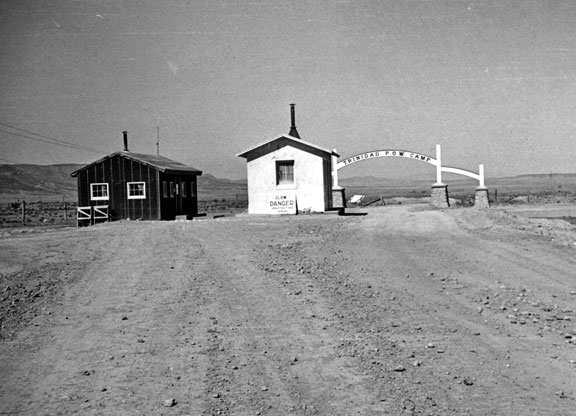

Trinidad, Colorado Springs and Greeley were locations for major POW camps during the war. Camp Carson, in the Springs, housed up to 12,000 men. All three were located in agricultural areas that were experiencing labor shortages and the camps provided prisoners to work in the fields. They were paid with coupons used to purchase goods such as tobacco and toothpaste. Depending upon rank, officers received $20 to $30 per month and enlisted men got ten cents per day.

Some prisoners were chosen to work for the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad, placing telephone poles, laying railroad ties and other labor intensive mountain projects.

Camp Hale near Leadville was the center of a scandal involving POWs after military officials seized three or four stills and 40-50 gallons of liquor. There were also reported incidents of collusion and treasonous acts by American military personnel at the camp. An American private, Dale Maple of the 620th General Engineering Corps, an identified Naziphile, made it possible for two Germans to escape from the camp to the Mexican border. Maple was arrested by Mexican immigration officials and was court marshalled for treason. Originally sentenced to death, he ended up spending life in prison.

Many of the German prisoners housed in Colorado were submariners, and due to the remoteness of the camps, the harsh winters and difficult terrain, escape attempts were rare. Other Germans housed in Colorado were part of the Afrika Korps, and had served under General Rommel in North Africa. The German prisoners were allowed to wear their army uniforms inside the camps according to rules of the Geneva Convention. Guidelines of the camp also dictated that German and American officers exchange salutes in the camps. The somewhat favorable treatment given to many of the German POWs drew criticism from the American public, but the camps were run in accordance with the Convention in the belief the American soldiers held in German POW camps would be afforded the same fair treatment.

In 1945, 200 POWs were housed at the high school in Center, Colorado, and 640 at the Armory Association Camp State Soldiers Home in Monte Vista. In camps such as Hale, prisoners were even allowed to publish their own booklets, such as Die PW Woche (The POW Week), but were not allowed to publish material of a political nature, and they consisted mostly of crossword puzzles, songs and cartoons. Fraternization between civilians and prisoners was forbidden, but a fascinating story published in The Colorado Magazine in 1979 by author Allen W. Paschal, tells of an affair between a Del Norte woman and a German prisoner stationed at a side camp (possibly Punche Valley). Apparently, she would drive out to a farm road in the evening to the waiting prisoner and would then return home. This went on for several months until the couple were discovered. The POW was then sent back to his base camp in Trinidad but no charges were ever brought against the Del Norte woman.

[InContentAdTwo]

Enemy Alien Internment Camps were also established nationally and in Colorado, mostly to house American citizens of Japanese ancestry. The Granada Relocation Center, known as Camp Amache in Prowers County is the most well known among them (see the March 2009 issue of Colorado Central for an extended article on the Granada camp) with a peak population of 7,567 in October 1942.

At the POW camps, German prisoners were allowed to participate in sports, watch movies, play musical instruments and take college classes. Colorado University even offered correspondence courses to the German POWs. After the war, most of the POWs returned home to Germany but some remained in the U.S., marrying American women and becoming farmers in the booming post World War II economy.