Article by Allen Best

Historic preservation – July 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

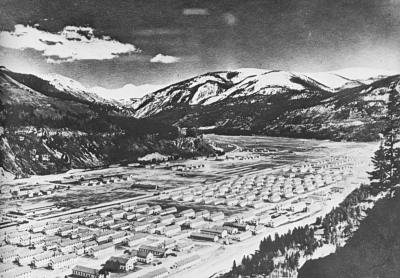

FOR THE CASUAL TRAVELER between Leadville and Vail, there’s little evidence of what was, during World War II, one of Colorado’s largest cities.

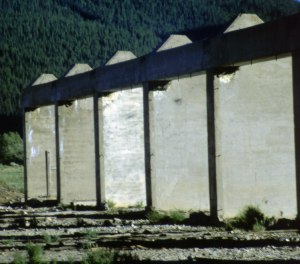

Bunkers, once used for a rifle range, sit a good distance from the highway at Camp Hale, home to the storied 10th Mountain Division. Concrete targets lie among tall grasses like toppled gravestones. At the far end are the crumbling foundations of warehouses. Amidst all this, residing incongruously at an elevation of 9,200 feet, like the bones of some mysteriously beached whale, are the columns of one remaining building.

But one other significant change is still evident and has proponents of historical preservation squared off against those favoring ecological restoration. It’s the river that no longer looks like a river.

To make room for this novel training of U.S. soldiers in snow and cold warfare during World War II, the valley floor was covered with 200,000 cubic yards of dirt and rock. And then, using steam shovels, the infant Eagle River was ordered into a ditch as straight as the streets that adjoin it. It is, by one estimate, 40 percent shorter than it was originally.

The soldiers used this valley for a relatively brief time, arriving around Thanksgiving in 1942, and by late spring of 1944 shipping off first to Texas, and then to Italy. There, they sustained some of the heaviest losses of any American division in the war. Soon after, most of the buildings were dismantled, and in 1966 the Army ceded this valley to the U.S. Forest Service for administration.

Since at least 1989 there have been proposals to restore the river to something resembling what William Henry Jackson saw when he photographed the valley in 1880. That photograph, taken from a narrow-gauge railroad line overlooking the valley, showed meandering water crowded by willows.

“That place stands out as an obvious place to get a fairly significant bang for your buck in terms of restoration,” says Mark Weinhold, a Forest Service hydrologist. “When you look at the national forest as a whole, you don’t see too many instances of this kind of disturbance on that scale.”

But the 10th Mountain Division Foundation, an influential group of veterans, wants to preserve the historical site. Except for the lower end, where the warehouses stood, they want the valley left intact as modified for their training. Earl Clark, president of the foundation, sees preservation of Camp Hale as perhaps his last effort to burnish the reputation and legacy of the 10th Mountain troopers.

“I’m 83, and the youngest of the vets is 77 or 78,” Clark says. “We’re fading from the scene. If we’re going to perpetuate the memory of the men who made this marvelous contribution, then it has to be the type of thing we’re talking about here. I feel very strongly that’s the case.”

Illustrious war record

The “ski troopers,” as they were commonly called, were unusual enough that even at inception in 1942 they were mentioned in the pages of the New Yorker. The U.S. military believed it needed an elite division, trained in the specialized warfare of cold weather and rugged topography, to rebuff a possible attack on Alaska, maybe even New England, or to drive out Nazis from Norway or the Alps.

Responsibility for recruitment was initially given to the National Ski Patrol. That group had argued that soldiers could more easily be made out of skiers than vice versa. Early battalions became a who’s who of skiers at the time, a small fraternity with a strong Ivy League taint. Noted mountaineers also flocked to the division, as did ranch hands, loggers, and others familiar with mountain ways.

Later, as recruitment stalled, non-skiers were drafted and taught how to travel on snow, painfully learning to make turns on the slopes of what is now Ski Cooper. Virtually none of this expertise in skiing was of value when the 10th Mountain finally shipped into Italy’s Apennine Mountains in early 1945, although rock climbing skills were crucial in a pre-dawn raid of Riva Ridge, a pivotal battle now commemorated by a ski run at Vail.

After the war, 10th Mountain veterans distinguished themselves in myriad lingering ways. Pete Seibert, who had been part of that assault at Riva Ridge, founded Vail. Larry Jump was pivotal in creating Arapahoe Basin, and Freidl Pfeiffer teamed up to launch Aspen as a ski resort. Others distinguished themselves in politics, academic research, and even shoe manufacturing. Bill Bowerman, track coach at the University of Oregon, used his wife’s waffle iron, to create the prototype Nike shoe.

At Camp Hale, meanwhile, little happened. As the war continued, German prisoners of war tore down the 245 barracks and most of the other buildings. Even the gymnasium where Joe Louis and Sugar Ray had once sparred in the thin air, and where Ronald Reagan’s first wife, Jane Wyman, had displayed her winsome charms, was disassembled. But when the U.S. Army transferred the final portion of the 247,000-acre military reservation to the Forest Service, nothing had been done to restore the Eagle River.

Historic designation

In 1989, Forest Service biologist Stephen R. Mighton proposed a plan that he thought would honor the history of Camp Hale while undoing some of the environmental damage. He envisioned creating 600 acres of wetlands and 13 miles of river habitat in the lower valley, but not touching the upper end of the valley, where the rifle range is located. He also imagined an interpretative center along U.S. Highway 24, which skirts the valley, to tell the story of Camp Hale.

With the U.S. Army pledging use of heavy equipment and Ducks Unlimited and other conservation groups offering money, Mighton calculated all this could be accomplished with a Congressional appropriation of $4 million to $5 million. However, when Mighton left Colorado for another assignment, the effort fizzled.

Instead, in 1992, the site was named to the National Register of Historic Places. Although a Forest Service official at the time declared the designation would not preclude wetlands restoration, a 1998 report discourages it.

Signed by Bill Kight, Forest Service staff archæologist, the report says that “from the perspective of cultural landscape preservation it is necessary to understand that the channeling of the Eagle River is a crucial element of the Camp Hale site.”

In other words, for visitors to understand this temporary Army post, they must see the river as the soldiers saw it, straight.

“To allow the River to return to its former channel or it to take active steps to re-establish the meanders in the river through Camp Hale would be an adverse effect to this National Register site,” the report adds.

By law, the Forest Service is required to consult with an advisory council, in this case Colorado’s State Historic Preservation Office. However, final authority lies with the supervisor of the national forest in question, the Glenwood Springs-based White River National Forest.

Clark, of the 10th Mountain Foundation, argues that Camp Hale deserves preservation because of the unusual training mission.

“We not only knew everything the average soldier knew, but we also had to learn mountain survival and skiing and so forth, skills that the average soldier just didn’t have,” says Clark, now retired and living in Denver.

Clark disdains “tampering with the stream,” except in the lower valley. Doing so, he says, “would be against the wishes of the 10th Mountain Division Foundation. We would oppose that very strongly.” River restoration, he says, “would destroy what the camp was. The historic site is Camp Hale, not the valley before it was Camp Hale.”

A rare opportunity

Weinhold and other hydrologists see rare opportunity. Most losses, such as those from construction of Interstate 70, are irreversible. But the Army long ago abandoned Camp Hale. They see no real impact to existing users. Bill Andree, a state wildlife biologist, whose district includes Camp Hale, also believes that wetlands restoration would discourage off-road vehicle use, which has hastened the spread of toad flax and other invasive weeds. “It’s a weed-infested gravel bar,” he says.

Also favoring restoration is the Eagle River Watershed Council, a non-profit citizens advocacy group. “The straightness of the river channel does not define the historical nature of the site,” says Caroline Bradford, executive director.

Even some 10th Mountain vets argue that the emphasis upon historical preservation is misplaced. Martin Murie, a retired biologist who served in the 10th Mountain Division, thinks restoration of the Eagle River and its natural flood plain is the most appropriate memorial to veterans.

“We’re loaded with honors already — highways named after us, a monument on Tennessee Pass, and more,” he says. “Now is the time, before it’s too late, for us to be truly generous, push for a memorial, not of our glory, but for those grand, hard, unforgettable mountains.”

For those travelers who do tarry to dwell on the history, the Forest Service has posted street signs as well as interpretative panels. Two bridges across the river are planned this summer, and $20,000 in planning has been invested in an interpretative center.

But street signs, panels and a grid of streets alone do not sufficiently commemorate a valley’s history, says Kight. More is needed, he argues, to truly commemorate the World War II veterans. “They truly did fight for world freedom and peace. If we forget that in our history, what do we have, when called upon to do the same?” he said in an interview conducted in 2002.

“I would ask what members of the public are as passionate about wetlands restoration?” he asks. “I haven’t seen them come forward, and until I do, I am going to stay on the side of the Camp Hale veterans.”

Allen Best enjoys skiing in Colorado and the history of skiing in Colorado, of which Camp Hale is a major part. He lives in Arvada and Eagle.