Article by Kate Booth-doyle

Rio Grande Natural Area – November 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

THE RIO GRANDE NATURAL AREA, which was officially designated on October 12 when President George W. Bush signed S. 109-56, winds through an isolated corridor of basalt rock and sand from the Alamosa Wildlife Refuge southern boundary to the Colorado/New Mexico state line.

Now, this 33-mile segment of river and riparian shoreline has federal protection to preserve its historical and archaeological features and habitat. The locals call this region “No Man’s Land”because the term implies inhospitable terrain.

And it is that. The region defies attempts by men to fatten their cattle on the sparse bunch grass, build a house, or successfully drill a well. But it does offer solitude, immense vistas, and a refuge for antelope, mule deer, black bear, and elk. The region also contains numerous archaeological sites dating back to 2000 B.C.

This No Man’s Land presents a wild, expansive sort of beauty that evokes tenderness in the hearts of those who crave and understand the necessity for such places. Those with experience along this stretch of heavily silted river, void of shade trees, know the meaning of inhospitable. Cheap land and low Costilla County taxes opened a portal for a few “back-to-the-land”enthusiasts some years ago. But the detritus of wind-smashed trailers and twister campers on the bare escarpment confirm the shattered hopes of those expatriates.

A discarded station wagon, complete with frayed curtains fluttering against crazed windows, once harbored an outcast from mainstream society. The tenant evaded detection from the occasional passerby like myself, and from the census taker, county tax assessor, social worker, and snooper. Strewn from the tailgate of his wagon were empty pinto bean cans, Wolf Brand chili, yellow corn and coffee grounds. This solitary soul must have skulked from his daylight-hiding place to curl like a coyote behind those curtains at night.

Water is the limiting factor to living here. Tiny communities — San Acacio, Eastdale, Jarosa, Garcia, and Mesita — are sprinkled a few miles east of the river. The residents are farmers and artists, who compete for the water resources, always praying for more rain or a sudden gush from the completely diverted Costilla Creek.

The windswept mesa is studded with fragrant sage, cropped by the harsh conditions of high elevation. The sharp winds of winter hold everything hostage when the temperature drops to 30º below zero. Snakes slither into dens buried deep within the canyon and coil into a snarl to hibernate.

Sparse soil blows into the cracks and crevices of the basalt landscape to provide slight purchase for the lichen, chamisa, fringed sagebrush and stunted shrubs that resemble tiny bonsai trees.

In May, searing sun cracks open the snowfields in the San Juan Mountains 150 miles upriver, and sends down a torrent of icy water. The annual flush ushers the San Luis Valley into its busy season of planting. Agricultural diversions reroute a significant volume of the river to irrigate potatoes, alfalfa, lettuce, and carrots.

Once the snowmelt is exhausted and the irrigation canals are full, the volume of water in the river diminishes and creeps slowly eastward through the silt-heavy Alamosa levee system to limp toward the state line.

As winter releases its grip, the lines in the face of Sugar Loaf come alive with arachnids, insect hatchlings and reptiles. The warm spring thaw entices tarantulas to flip open the trap doors of their underground houses and explore the wrinkled surface of Witch’s Rock. Spring wind howls over this land of staunch solitude, and colorful bull snakes and rattlesnakes coil in the shade of rabbitbrush.

I drove my ’88 Ford F-250 truck with camper out to Witch’s Rock, rattling down half a mile to a flat place above the river. Perched atop my camper one morning, I sipped hot coffee and watched the tarantulas creep from their underground homes to test the air. I think the weather was still too chilly for the snakes to expose themselves.

By mid-summer the river south of La Sauses narrows to little more than a muddy stream. Cattle easily cross the shallow river, mowing down any vegetation they sniff out. The girth of the floodplain expands due to the alluvium deposited on shore. Under the assault of skinny renegade cows that escaped capture during last October’s round-up, young willows struggle to hold on.

THE BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT (BLM) has successfully proven the regenerative capabilities of willow and poplar by fencing the cattle out of small riparian acreages. Shrubs, willow, cottonwood and native grasses thrive within these protected areas.

Lobatos Bridge, or Stateline Bridge, built in 1892, swings over the Rio Grande about 8 miles north of the New Mexico state line. Here, the flat landscape along the river transforms itself into a dark, narrow gorge. The antelope and mule deer gaze down from their waterless mesa into the richly green, riparian zone along the river. An occasional black bear trundles along a serpentine canyon path for a drink and to cool off.

Above the rim of basalt, the thermal blue skies carry peregrine falcon, golden eagle and red-tail hawk, hungry for a meal of mice and kangaroo rats. Their cries echo against the quiet æries tucked in the canyon wall.

One might inquire why this insalubrious chunk of real estate needed federal protection? The west side of the river is federal land, managed by the Bureau of Land Management. The BLM issues permits for cattle grazing, mining, and other land uses that extract natural resources. Past policies turned a blind eye to the value of untrammeled landscapes, and the federal agency frequently compromised the scenic beauty of isolated and sparse landscapes similar to this one for oil and gas leases

But in 1997, the BLM embarked on a new vision for the Rio Grande corridor — from the Alamosa Wildlife Refuge to Velarde, New Mexico — which recognized the value of scenic beauty, solitude, protection of wildlife and raptor nesting in the canyon, along with protection of historical and archæological sites.

THE PRIMARY IMPETUS for protection of the river corridor came when the BLM determined this reach qualified for federal Wild and Scenic designation. Panic struck the water users of the San Luis Valley. They feared this designation because they thought it might mean a federally reserved water right would be imposed to assure a specific flow through the 33 miles. Such a water right could curtail diversions upstream and deny essential irrigation waters to farmers holding senior water rights.

The Rio Grande Water Conservation District assigned its attorney, David Robbins, to find a solution. Robbins researched possibilities and drafted legislation for protection of the corridor which wouldn’t compromise the water rights of the upstream farmers. He also engaged the San Luis Valley Ecosystem Council in a collaborative approach to design legislation that would be palatable to the environmental community. Thus, a bill was written, revised several times, and introduced in early 2005 by Sen. Wayne Allard.

The east side of the river is private property, and the threat of losing the river corridor to development is real. Thousands of acres were purchased for development in the 1970s. The developer, Rio Grande Ranches, sliced up the high desert into small parcels, and left a strange grid-work crisscrossing through the middle of nowhere. Thus far, no fortunes have been made, but people from Germany, Japan, and California have bought pieces of what they hoped to be their desert paradise, sight unseen. Fortunately, they seldom come to this remote location in America to build their dream homes.

The few reclusive folks who have settled here have built small shacks or simple homes with solar or wind powered electricity, when they could afford it. Newcomers quickly discover that drilling a well for water can prove expensive and difficult and usually yields dry volcanic dust as the only geyser. This major drawback seems to discourage most city dwellers from packing up their condos and heading into the rugged Rio Grande high desert.

Those who are hearty enough to live out here would rather not have neighbors within earshot or sight. Signs scrawled in rough black paint insist that trespassers BEWARE. Thick-necked dogs roam the property lines outside weather-beaten fences. The people who shove up against the harsh wind of No Man’s Land either make peace with roughing it, or the solitude splits open their darker psyche. Those who are drowning in dry despair gather their disappointments and hitch a ride out.

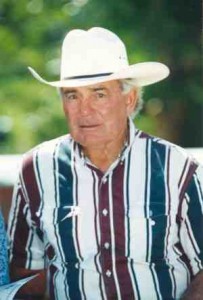

MY HUSBAND, DICK, purchased five acres of riverfront Rio Grande Ranches property in late 1970 with the intention of building a place on the fringes of society. He said he had no need of close neighbors and that still holds true today. “I wanted to wake up like they did 150 years ago and see nothing of mankind.” He now resolves to do absolutely nothing with this land, but leave that tiny segment to the badgers, burrowing owl, and wild horses.

Several other landowners hold a similar vision. I joined the effort to purchase property adjacent to the river for unpaid back taxes with the mission to consolidate the properties and form conservation easements to further protect the corridor from development. The success of our strategy has yet to be seen.

But the Rio Grande Natural Area legislation passed the U.S. Senate on July 26 and the House of Representatives on September 27. The President signed it on October 12. So now No Man’s Land has some protection.

Kate Booth-Doyle lives near Del Norte, and has written for many publications. She is also a guide, outfitter, naturalist, and rafter.