Brief by Central Staff

Historic Trails – July 2003 – Colorado Central Magazine

Even though the National Park Service was not in favor of it, the Old Spanish Trail is now a National Historic Trail. The designation bill, pushed by Rep. Scott McInnis and Sen. Ben Campbell (both are Colorado Republicans) passed Congress late last year and was signed on Dec. 4 by President George W. Bush.

At Campbell’s behest, the Park Service studied the trail in 2000 and issued a 152-page report, which concluded that the Old Spanish Trail met all of the criteria for designation, except one: “among historians, there is lack of consensus as to whether or not the Old Spanish Trail is nationally significant.”

Whether the historians agree or not, the Old Spanish Trail now joins better-known routes — like the Oregon, Santa Fé, and Pony Express trails — as part of the National Historic Trail System.

This doesn’t mean that federal engineers will map the route, then reconstruct it to 1840 standards so that you can take a pack mule from Santa Fé to Los Angeles. It means that there will be interpretive signs and the like along the route, and nothing will go on private land unless the landowner wants it that way.

The Spanish Trail was originally developed by Spain’s New World Empire in the 1820s to connect two isolated outposts: Santa Fé and Los Angeles. Although wagons traversed parts of it, it was basically a pack route, often used by horse thieves and slave runners.

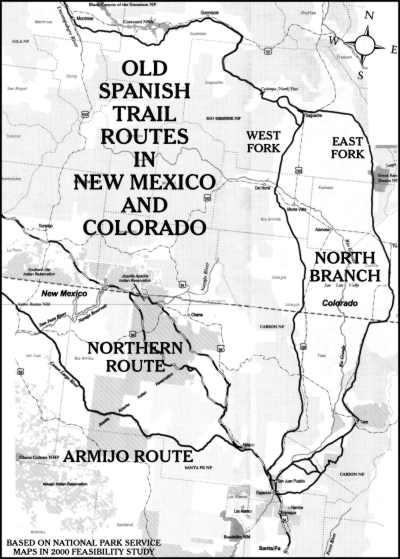

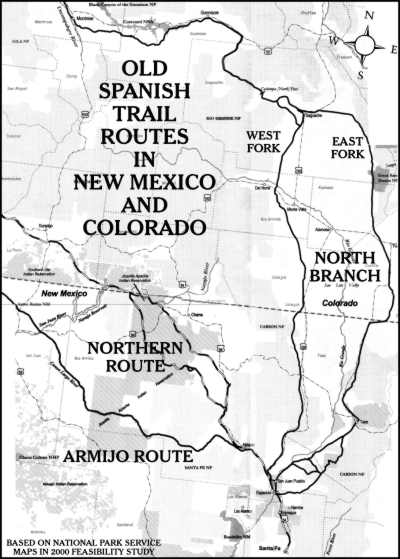

On this end, it’s more accurate to speak of “Old Spanish Trails” than of a “Trail,” because there were several routes to the West Coast.

They all started in Santa Fé and went north to Española. The Armijo Route went northwest to Abiquiu, then west and a little north toward the Four Corners and generally west from there to Littlefield, Ariz., where it joined the other branches.

The Northern Route went northwest from Abiquiu, and skirted the southwest corner of the San Juans to get to Green River, Utah. The Northern Route is different from the North Branch, which spent the most time in Colorado.

From Española, the North Branch quickly split into the East Fork and West Fork, with the Rio Grande between them. Both entered the San Luis Valley, and joined at Saguache to cross Cochetopa Pass to Gunnison and then westward to Green River, Utah, where it rejoined the Northern Route. And then the Northern Route joined the Armijo Route near the place where Utah, Arizona, and Nevada come together. They split again before all coming together near Barstow, Calif., for the last leg into Los Angeles.

Just describing all those forks and branches means that there’s plenty of work ahead for those marking the Old Spanish Trail.

In ways, it’s odd that the trail designation was pushed by legislators from Colorado, because in horse-and-wagon days, trails tended to avoid Colorado (especially Central Colorado) on account of the mountains.

The Oregon Trail (and its related California and Mormon trails) went to the north, and the Santa Fé Trail went to the south (although its Mountain Branch did stay in Colorado long enough to cross Raton Pass). And even a pack route like the Old Spanish Trail had branches that barely touched Colorado.