by Daniel Smith

There are many Colorado wildlife legends, myths and stories, but none can match the fabled chronicles of Old Mose, the giant grizzly who “terrorized” settlers in Park and Fremont counties more than 110 years ago.

He was the badass of all the big bears presenting major challenges to ranchers and homesteaders in the mountains of south-central Colorado around the turn of the century.

His story, inflated and sensationalized in national publications such as Outdoor Life after his dramatic ending in a stand of aspen in Fremont County in 1904, is a glimpse of the environment and attitudes of early settlers as much as the amazing tale of a grand old denizen of the territory.

The Old Mose legend begins with a brutal death.

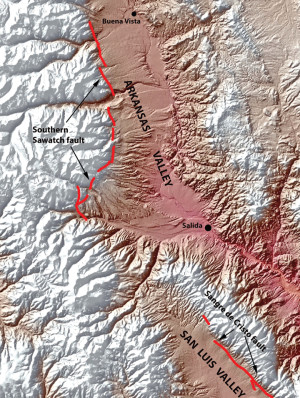

In November of 1883, a hunter, Jacob Radliff, had a terrible encounter with a grizzly while hunting with friends on Black Mountain, about 45 miles southeast of Fairplay.

He reportedly had seen bear tracks but didn’t follow them at the time, because he was after deer and elk.

As he reached the edge of a meadow, a huge bear rushed out from the brush and attacked him. He got off a shot, but the bear, described as “cinnamon,” savaged him, tearing his scalp away, breaking many bones in his legs and ankles and clawing at his face. He was left for dead when his companions found him. Radliff was taken by his fellow hunters to a nearby ranch and a rider went for a doctor in Fairplay, but he died the next day shortly before the doctor arrived; his last words were a warning to his hunting partners.

“Boys, don’t hunt that bear.”

Whether or not that particular bear, most certainly a grizzly, was Old Mose or not (more on this later), the legend of the killer grizzly of Black Mountain was born.

The grizzly population in the state was shrinking in that era, with the human population spreading and encroaching on wildlife habitat as never before. According to Western Wildlife Outreach, grizzlies at the time were being extirpated rapidly: from 95 percent of their original western range between 1850 and 1920. Unregulated killing of bears between 1920 and 1970 eliminated another 52 percent of surviving populations. Man eliminated 98 percent of the big bears over a 100-year period. This was the inevitable trend occurring for Old Mose and a small population of grizzlies in the south-central mountains back then.

At the time, bears preying on cattle were fairly common, judging by the stories about ranchers suffering many losses of livestock, especially young calves, and it was a standard reaction by settlers to mount “expeditions” to hunt bears to cut their losses. There were even other grizzly bears given nicknames, like “Old Four Toes” and a giant named “Old Silver” in the reports of livestock predation then.

Shortly after Radliff’s death, the unfortunately named Wharton Pigg, an outdoorsman and from all reports, an expert hunter and shooter, becomes part of the legend.

Pigg, a Missouri transplant helping on his family’s potato farm during his early life, hunted the killer grizzly he heard about. He entered college in 1886, but he was back home in Park County’s Currant Creek the next year for spring planting when an uncle wrote about seeing the tracks of three bears around Cover Mountain, near Black Mountain. He took his new Winchester big game rifle and went. The trio turned out to be a big sow grizzly and two big cubs. She was thought responsible for several area livestock deaths over the years, but could not be trapped or shot. A reward of 75 dollars was offered.

Pigg found the bear trio in heavy brush and killed first one cub, then the sow when she charged at him in reaction. The other cub ran off toward Black Mountain. After college, Pigg continued to hunt for the notorious Black Mountain killer bear regularly, even mapping his range from the varied reports of a big grizzly.

The definitive work on this remarkable bruin is Old Mose, by James E. Perkins, published in 2002. It contains many detailed and surprising aspects of this story. In researching the story at the Royal Gorge Regional Museum and History Center, I was told that Perkins’ research files there were enormous, and the detail in his book underscores that. It’s apparently still available online and at the library and is an absorbing read. James Perkins notes that the name Old Mose came from Pigg’s comment that the bear seemed to have no set territorial route, but seemed to “mosey around.”

Interestingly, in 1894, a hunter named J.J. Pike killed a very large grizzly on Thirtynine Mile Mountain, northeast of Black Mountain, after spending multiple months himself over the past three years hunting for Old Mose. Pigg was depressed that someone possibly had shot “his bear.” It reportedly weighed near 1,000 pounds and “completely filled a wagon box.”

But in 1895, more large-clawed tracks were found around Black Mountain and Pigg, made rich by a gold mine operation in Cripple Creek, came back to hunt his nemesis. He tracked him, sometimes very closely, but the bear always proved elusive. Part of the Old Mose legend is that he was very savvy about avoiding hunters.

In 1898, after his gold strike, Pigg married a woman from Texas, and bought the sprawling Stirrup Ranch in Fremont County between Black and Waugh Mountains in 1900; he continued to look for Mose while running the ranch.

At one point Pigg tried a new approach. He had a large trap made and placed it in nearby ponds the big bear was known to frequent. He placed it a foot underwater, and about two weeks later, Old Mose was found roaring and thrashing in the pond trap by a boy who had been regularly sent to check on the trap. Before armed men from the ranch arrived, Mose was gone, the trap dragged some distance from where it had been set, with two bloody grizzly bear toes still in it. He had escaped, but at a price. From then on, the story goes, Mose left his unique footprint, with a mangled left hind paw, wherever he roamed in the area.

Pigg continued to get reports of Mose’s preying on livestock from hunters and ranchers, and in 1903, even suffered the humiliation of allegedly losing a 3-year-old Hereford bull to him from his own ranch near the base of Waugh Mountain. He poisoned the carcass, Perkins wrote, but Old Mose wouldn’t come back near it.

That summer, the skeleton of a man was found with boots, spurs and a carbine on nearby Thirtynine Mile Mountain. Rumor held there were large teeth marks on the rifle and the man’s bones. Fuel was added to the ‘killer’ Old Mose story. Additional supposed prospectors gone missing while seeking to gain a bounty for bagging Mose and even more reports of livestock being killed in the area only enhanced the spreading legend.

Pigg hunted for Old Mose for many years without success and in March 1904 was introduced to a noted bear hunter, James Anthony, who had come to Cañon City with a large, well-trained dog pack and who had killed a number of bear and mountain lions. They agreed to go looking for Old Mose in the spring of 1904, Pigg telling Anthony he was certain he knew his range well enough to find him just after he left his winter den.

After many frustrating days of searching, it happened. Riding back toward Pigg’s ranch, Anthony saw his dogs get on a scent and loosed them while Pigg, seeking to somehow get there first, apparently tried to find a shortcut to the bruin as he encountered the dog pack, something that would have been a new and confounding experience for the bear. Then Pigg heard Anthony shooting.

Perkins’ description of Old Mose’s final stand against Anthony, near his Black Mountain home, is worth sharing:

“… after the dogs had him at bay, and Anthony had fired a shot that hit Mose in the throat. He was bleeding and moved uphill toward Anthony until he fired again, twice, apparently missing. The bear turned around at the sound of the shots and Anthony stated: ‘As he went I ran in closer and shot him behind the shoulder, the bullet coming out of his breast at a point generally called the sticking place. He faced me at eleven steps distance (my emphasis) and came on with head low.’”

Next, Perkins notes, Anthony shot at Mose’s head and missed, but fortunately for him, the bullet hit the spinal cord near the neck and, he says, traveled down through the spinal marrow. Other accounts say he was shot in the head.

“He sank slowly to the ground,” Anthony wrote later, “raised himself partly up once or twice and was still except for his breathing which continued for some time, and even after he ceased breathing he seemed a threatening dangerous bulk, as in his life he had been a terrifying, blood chilling destruction to men and cattle for many years.”

An apt description, I suppose, if you’re the victorious hunter, but it also serves nicely, it seems to me, to aggrandize his legend. Perkins notes that all through the encounter with the dog pack and the hunter, Old Mose had not made a sound.

[InContentAdTwo]

The news of the demise of Old Mose brought out the crowds as Pigg took his carcass by wagon through a storm to Cañon City – an estimated 2,000 people came to see the monster bear. A photo from the event has Pigg and Anthony standing on boxes next to the hanging carcass. A description in the Cañon City Times said “Old Mose measured eight feet and six inches from tip to tip and his savage claws were six inches in length, while his ugly tusks were fully three inches long.”

Perkins wrote that Old Mose weighed 775 pounds field-dressed, which meant an estimated 1,000 pounds live weight. Shot and killed a few days out of hibernation, this meant that Old Mose could have weighed as much as 1,300 pound in the fall of the year. By any measure, in any year, that is one helluva huge bear.

The legend was burnished with stories about any number of bullets found in his body, one perhaps from the gun of old Radliff they said, and while Anthony had the hide preserved for himself, to make a familiar open-mouth bear rug, Cañon City residents purchased the meat for their tables. Anthony had the fur, skull and head preserved. He later donated Old Mose’s remains to the University of California, Berkeley Mammalogy Department, part of an impressive 500-bear collection.

In the late 1940s, Cañon City officials and the then-museum curator tried to get Old Mose back, but the UC Berkeley Museum of Anthropology declined, citing Anthony’s original donation, and saying the hide was not in good enough condition to ship.

In his book, Perkins research reveals what one might begin to surmise from the reports in the media of the day – the legend of Old Mose is mostly myth, inflated and made more spectacular because, well, how many legends ever shrink?

Perkins astutely contacted the UC Berkeley Mammalogy Department and requested to have a tooth removed and sectioned by an expert at the Arizona Fish and Game Department. He undoubtedly suspected Mose could not have singlehandedly caused such a reign of terror over more than 25 years (some said over 40 years at the time). The expert, who had dated hundreds of bear teeth, found Old Mose was in fact a sow grizzly, estimated to be between just 10 and 12 years old. It was in the prime of life, in other words, and not born at the time Radliff was attacked in 1883.

The irony of the fact Old Mose was not old at all is disappointing, naturally. Perkins holds that Mose’s legend is really a compilation of grizzly incidents from that era, conveniently rolled into one mammoth bear, the lore distilled into a mythological creature.

I suspect that the huge bear killed near Waugh Mountain in 1894 by Pike, which “filled a wagon,” (a photo reveals that was not an exaggeration) and which reportedly weighed in at nearly 1,000 pounds, could have been another chief suspect. One newspaper at the time called him the ‘father’ of Old Mose; I’d like to think that’s a possibility. The Denver Post heralded: “King of the Grizzlies is Dead” and repeated the exaggerated stories of his exploits, even using the photo of the grizzly shot ten years earlier by Pike to represent the carcass of Old Mose.

Until fairly recently, there had been reports of grizzly sightings in remote areas around the lower San Juan Mountains, but most experts seem to think no sustainable populations could exist there now.

The very last grizzly killed in Colorado technically occurred as late as 1979, when a bow hunter and guide, Ed Wiseman, came across a smaller sow grizzly in the southern San Juans near the New Mexico border and was attacked and nearly killed. Press reports indicated Wiseman tried to play dead, but the bear would not stop mauling him, possibly because it had a cub. He reported he managed to grasp one of his hunting arrows, and plunged the sharp head into the bear’s throat, slicing a major blood vessel, and also stabbed it into the bear’s rib cage. It then collapsed and died.

It’s quite a story, and reports at the time indicated Wiseman even took a lie detector test. That bear, however, was thought to have been a non-native grizzly that had perhaps wandered down from Wyoming.

Old Mose was also fabled in a newspaper ad from the then-Public Service Company of Colorado by longtime artist Ben Cooper, who himself had a ranch in the vicinity of this story, and who died in May of 2014.

The copy with the ad art showing Old Mose fending off the dog pack in his final moments reads in part:

“It’s true, some predators in our state … must be controlled. But others must be protected. While we can never hope to restore a true natural balance, or to bring back our once-numbered grizzly bears, we can and must regard predators with enlightened tolerance and respect for their place in the scheme of things.”

In 2006, Adams State College (now University) in Alamosa changed the name of their athletic teams from the Indians to the Grizzlies, and a 12-foot bronze statue of a (naturally) menacing Old Mose by artist Jim Gilmore was dedicated. It stands in the center of Grizzly Court with a plaque proclaiming some of the more extravagant parts of the legend. The statue is larger than Mose actually was, but that seems appropriate, with him being bigger than life even while alive.

In some sense, perhaps Old Mose was aware of the changes in his environment near the end of his life, or perhaps not. Wildlife populations were certainly diminishing, his home range being invaded by human populations and the inevitable conflicts they brought.

If you tend to favor the side of wildlife, his death by dog pack and rifle may seem almost tragic. If, as was the mindset of the time, you see him as a rogue bear, used to preying on livestock (and maybe humans) instead of a more natural existence, you might agree he was a major nuisance, needing to be eliminated.

Old Mose will continue to be the stuff of robust legend, an animal enshrined in Colorado history, and his story engenders more than that – a look back in time at our impact on the nature of wildlands, and an unfortunate reminder that there once existed a wilderness we can no longer have any relationship with ever again.

Old Mose’s spirit can only mosey through our imaginations now.

Daniel Smith is a former Denver Post and Rocky Mountain News reporter-photographer and broadcast journalist now living in not-so-quiet contentment in Salida.