By Martha Quillen

They say that it takes courage to face old age, but what about the alternative? Although death delivers the inevitable end for all of us, I tended to worry more about old age – especially Ed’s old age. I thought that Ed and I would be together for at least another ten or fifteen years, and I wanted to make them good years.

Of course, medical literature is full of warnings about sudden, lethal heart attacks, but Ed was not one to dwell on what could go wrong – be it money-wise, work-wise, or health-wise. I was the worrier in our family, but I was intent on fixing what was already wrong.

Ed had diabetes and needed a special diet and plenty of exercise. In this age of electronic communication, big metro newspapers were cutting back, and The Denver Post had stopped delivering its Monday through Saturday editions in western Colorado. Ed was down to one column a week, and our financial future looked a bit precarious. So I was working more hours and Ed was sending out more queries.

At sixty-one, we sometimes felt as if we were going to have to start all over again. We weren’t the only ones; other friends in the business were likewise discouraged.

Yet Ed seemed to be doing well. He had slashed sugar, meat, potatoes, and excess carbs from his diet. He’d quit smoking, and had gotten his blood pressure and sugar levels under control. Ed’s self-improvement regimen wasn’t easy, but he worked at it, and in recent months he seemed happier. He was writing more and better, and taking on new projects, and spending more time with friends. He was working on a novel and a news story, and planning a patio project.

But on June 3, 2012 at 3:11 a.m. all of that became a moot point. Ed was pronounced dead at the Heart of the Rockies Regional Medical Center.

The situation had looked dire from the moment I found Ed, about an hour earlier. He was sitting up in a chair downstairs with a book at his side, but was totally unresponsive. I called 911, and with the operator’s instructions I somehow managed to get Ed onto the floor without slamming his head against anything. But Ed was curiously limp and didn’t so much as turn his head or stiffen a muscle in response.

Ed’s death was the most surreal experience in my life. I’ll always remember how Salida looked that night – with the ambulance lights pulsing and the street lights glowing. At the hospital, everyone was extraordinarily kind and asked the necessary questions with tact and patience. But as they continued to work on Ed, I realized how bad his condition was, and started to wonder why I had gotten so obsessed with his diet. Why had we spent so much time and energy overhauling his health care habits? Why had I pushed him so hard to quit smoking? What sort of things might we have been doing instead? Visiting? Traveling? Eating out?

At the same time, I was wracked with guilt about not doing more. Could I have saved him if I had just tried harder? What if I had understood things better and pushed more? It was the perfect emotional storm, mounting into contrary surges.

After Ed was pronounced dead, I clutched his hand while we waited for the coroner. For a moment I thought of taking my husband home, because I couldn’t face the idea of leaving him in the hospital. The hours ticked by slowly, but I was glad to spend them with Ed. And by the time I left, I realized that he was truly and irrevocably gone. My husband would never go home with me again.

For 42 years, our lives revolved around news and politics. Just a few months ago, we were watching the news about the 2012 national primaries, but during this campaign we often turned off the television and played Scrabble or read instead.

I used to like political races back when we were working at newspapers and often attended the forums and dinners given by both parties. But in recent decades, I’ve felt alienated by the duplicity, lies, exaggerations, and self-righteous rhetoric that dominates U.S. campaigns.

And I hate – really hate – the mean-spirited, hollow religiosity that has become such a huge part of our political system. It’s bad for our country, our culture, and our religious institutions, and it downright offends my sense of religious ethics and integrity. What kind of Christianity is it that champions our right to kill trespassers and keep ailing immigrants out of our hospitals? If you ask me, all of this public piety has only served to highlight our hypocrisy and erode our political system and make a mockery of our faith and traditions.

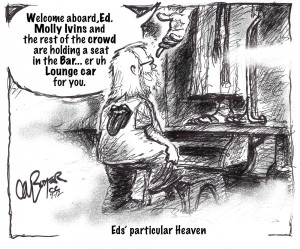

But after Ed’s death I saw a whole different side of American public life. People showered me and my family with a rich and spontaneous outpouring of love; they gifted us with cards, letters, food, flowers, donations, hugs, and sympathy. Many of them knew Ed personally, but most didn’t. Yet they told us about how his life had touched theirs and how much they would miss him.

Many people who had never met Ed, wrote about how they had corresponded with him for years. Others told us how a column or line delivered by Ed had inspired them. Neighbors came to the house; acquaintances offered aid; relatives came from afar; and strangers called to tell us how much they had loved Ed’s writing.

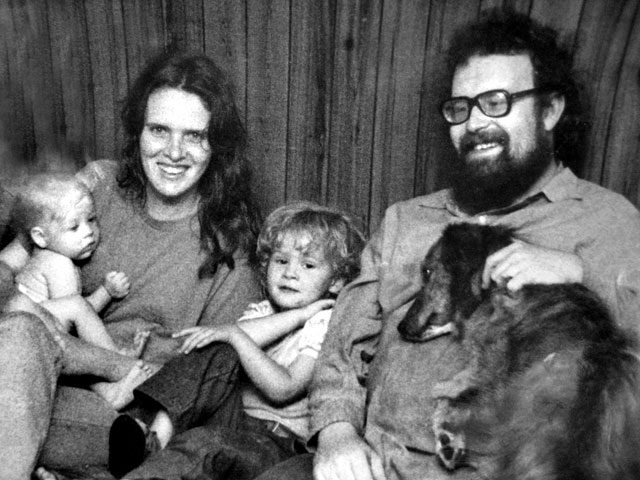

Old acquaintances shared stories that helped me remember the bright, funny young man I met and married in 1969 – that kid who wanted more than anything to be a writer and live in the Colorado mountains.

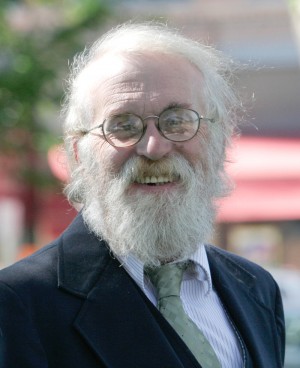

People sent us letters about Ed the history buff, and Ed their boss, and Ed the trivia expert, and Ed the writer. Those letters called Ed a jewel, a sage, an icon, a treasure, wise, bright, honest, and brilliant. It was the most astounding flood of comfort and affection I have ever experienced, and it made me feel so much better about this country I live in.

But I also remember another Ed, the private Ed, who loved his dog and believed that his two daughters had turned out as near perfect as any children could be. That Ed was not always so brilliant; he frequently forgot to take out the garbage or do the dishes that he’d promised to wash. And sometimes that Ed would turn to me out of the blue and announce, “You are so beautiful,” and he meant it, even when I was sixty, and tired, and my hair was a mess.

Now I sometimes miss that Ed so much that it seems absurd that the sun still rises overhead without him being here.

My husband didn’t care about money, or clothing, or accouterments, or who was who, but he loved his home, and Colorado, and history. And if there’s one thing I think everyone should remember about Ed Quillen, it’s that he loved being part of a community and reaching out to other people and having them respond. And you gave him that. Ed became the writer he always wanted to be because of all of you who read his columns and appreciated his work.

Thank you all, so much.