By Richard R. Cuyler

Up close, Mount Princeton is an ugly pile of granite; from a distance, it is beautiful in all its changeability of weather and seasons.

At 71, should I have known better? Six of us, Princeton University alumni and friends, gathered for the annual climb up “our” eponymous mountain. Since it was mid-August, I dressed in my usual eastern gear: shorts, T-shirt and hiking boots, with a fleece pullover and a poncho for good measure. We met in a drizzle, so out came the poncho. I was chilly, but why break out the fleece when the climb would soon warm me up? Our late start didn’t concern me. I knew about the furious afternoon storms but thought they couldn’t happen on an overcast day, since heat wouldn’t build up, a condition I understood as necessary.

First the road, then the trailhead, then the short stretch of tundra before the boulders, interrupted occasionally by sections of rough trail. I could tell the air had become thinner, but the light rain had stopped. I was warm and content. Although I had to stop frequently to catch my breath, I was exhilarated. Sometimes I could hear water purling through the jumble far below my feet. Everything, including my knees, was right with the world.

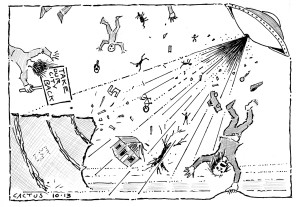

Treeless, open heights under dark skies seemed ominous enough, but we pressed on. About a quarter of a mile from the summit, we heard thunder; it didn’t sound very close. We’d do it. More rumbles – louder, closer. Our summit pictures show apprehensive faces. Then came a huge explosion of sound we could not ignore. If the capricious gods had not yet eliminated us with their cannon, they were certainly finding the range. They added hail, then made it travel sideways with an imposing wind. Had I more hair, I might have felt as though it was standing on end, as others did.

This might be serious, I thought, as I bounded down as best I could, slipping from boulder to boulder, with the poncho an added menace in the wind. The storm passed over, but the energy used to reach the summit and outlast the elements had abated as well. I was cold and my fingertips were numbing in my wet gloves.

I was with two women, but where were we? In our rush to some safety, tracing the trail back had not been on our minds. We saw campsites and a lake far below us. Why not get down the mountain that way? We negotiated a short but nasty wall, but soon found our way blocked by a more definite drop. We backtracked, then started to argue about what to do. We were getting so tired and confused we knew we couldn’t effectively help ourselves. Calling for rescue seemed the only option.

Mount Princeton sports one happy hallmark of civilization – a cell tower – and all of us had phones. When we called for help, almost right away a man from Chaffee County Search and Rescue returned the call. I gave him our GPS position from my wrist-wonder Garmin, and he told us what to do. Relief came and energy returned. We started down the way we had gone before. Then he called again, saying he had misplotted our position, and that we should climb up, heading north and east to a saddle below the summit. He hoped we could get there by nightfall, but if there was more lightning, we’d be on our own, since he would not dispatch a team if they would be in danger themselves. I now felt a different kind of cold.

Again we backtracked and realized we were looking at a huge scree and boulder field that appeared to pitch toward us at a 45-degree angle. Discouraged and scared, what could we do except follow the directions? My mind was not its usual rational instrument, instead registering the dread that we would probably die unless the rescuers could contact us.

Already one of the women had taken an awkward slide for forty feet or so, banging an arm hard and giving her leg a good twist. As for me, the whole seat of my shorts was ripped out. The rocks had made a good start on my underwear and had done some damage to my rear end as well. Our snacks had been consumed, it seemed, in some distant time past, and we were rationing our small store of water. We climbed, stopping often to pant and call up resolve as sunset and night became more of a possibility.

We whistled, and someone whistled back. They saw our flashlight beam and we saw theirs. Salvation! They had warm clothes and gloves and hats – and energy-rich snacks. I was shaking, hypothermic, unsteady.

At midnight, we started down. I was worst off. A rescuer tied a rope around my chest and held onto it at my back. I stumbled and lost my balance, and I had to stop often. Patient and professional, the team kept us going without ever urging us to a faster pace. At 3:30 a.m., we arrived at the trailhead; at 4:30, we were off the mountain and in the rescue trailer.

My wife drove the two women and me back to our house, where she put out towels in the bathroom and pointed to the guest bedroom. She took me to the emergency room, where I was found to have no serious problems. I enjoyed the hot soup much more than having the grains of rock tweaked out of my skin. Of course, no Neosporin tube could come with enough to cover the scrapes – some deep – to my legs, arms and bottom. The quantity I used made me wish I had stock in the company.

So this forbidding mountain accidentally became a part of me. Quite simply, I could have died. That possibility gave my life a shadow from which I live more compassionately and fully. There were less extreme lessons: I was not surprised to find out how selfish and needy I was, because each of these components was a part of me before; now they each have an exponent attached. I wish I had been braver, but I came to realize that I had to forgive myself because I had seen the possible end of my life’s rope. The whole ordeal, an extreme endurance test that I struggled to pass, has instilled some perverse pride – and the definite hope that I will not be required to take such a test again. I had “frost nip” down to the first knuckle on all of my fingers. Literally, the experience left me numb, and faded slowly over the months as the nerves returned to health.

As a Princeton graduate, I realize I’m supposed to be an intelligent guy. I have questioned that assumption before but never as deeply as on that mountain. I feel like that donkey who, although he was smart, needed to be conked on the head to focus his attention. Mount Princeton certainly got my attention and made me more focused. I also know the answers to the questions I should have asked before attempting the ascent. The mountain just stands there, implacable, uncaring. It posits no ethical code, points with no moral compass. But for me it became the rough, capricious actor in a personal morality play where I worked out some conclusions face-to-face with its dumb presence.

Granite hardness and majestic beauty: I’m glad I know both and that they have become an integral part of me.

Although retirement offered many chances to be useful, Dick decided to scribble instead.