Article by Steve Voynick

Agriculture – March 2002 – Colorado Central Magazine

WHEN A LIFELONG RANCHER passes on, it seems almost obligatory to bring up the well-worn metaphor about “the end of the trail.” But in the case of Mel Coleman, the Saguache rancher whose name is synonymous with natural beef, the phrase doesn’t really fit. That’s because in his life, when Mel came to the end of any trail, he never stopped or turned back; instead, he looked ahead to find an alternative route. When Mel died on February 3, that was one of the things he left behind — an alternative route that is making an impact on life in the West.

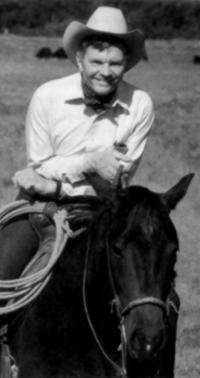

Glenn Melvin “Mel” Coleman was born in 1925 in Saguache, the great-grandson of pioneer families who homesteaded there in the late 1870s.

Mel wasted no time growing up. At age ten, he was already handling horses and helping out with the ranch work. Less than a year out of high school, he was a Navy radar technician aboard the cruiser U.S.S. Vicksburg at Iwo Jima and Okinawa. After the war, he returned to Saguache to marry his long-time sweetheart Polly Curtis, and was all of 25 years of age when he took over the management of the 240,000-acre Coleman Ranch, a spread that stretched from Saguache west to the Continental Divide near Cochetopa Pass.

Few people outside the San Luis Valley would even have heard of Mel Coleman, had it not been for the national economic crisis in agriculture that began in the 1970s. Across the country, farmers and ranchers were losing the battle against higher operating costs, depressed commodity prices, and the soaring interest rates on neck-deep debt. To stay in business, many farmers began seeking alternative approaches in new products and niche markets that would hopefully prove more profitable.

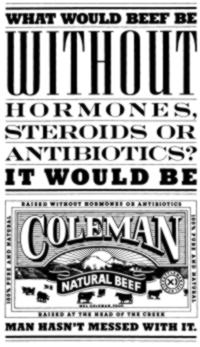

Ranchers were even worse off than farmers. Concerned about the routine use of growth-promoting antibiotics and hormones in cattle, consumers were turning away from beef in droves. And with the beef-processing and marketing industries mired in federal regulation and under the heel of corporate control, no one had yet figured out an alternative approach to cattle ranching — that is, until 1979, when the Coleman Ranch faced foreclosure.

Ranching wasn’t just a job to Mel Coleman, it was a way of life that represented everything that was good about the West. He believed that ranches were the greatest place in the world to raise a family, and that they brought together some of American agriculture’s best elements like good grass, clean water, and open space. The Coleman Ranch had already been in the family for four generations, and Mel wasn’t about to lose it on his watch.

IN 1980, with the help of his family, Mel figured out a way that just might fend off foreclosure. He was going to raise cattle without using growth-promoting drugs, then process the beef himself and market it as “natural beef” at a premium price high enough to generate a ranch-saving profit.

When I first met Mel in 1986, Coleman Natural Beef, Inc., was already six years old, and I expected things to be a little further along.

On a bitterly cold, windy March morning in Saguache, I walked into the “corporate headquarters,” a small, one-floor, red-brick house that showed the wear of every one of its 90 years. Mel, wearing a big Stetson and a heavy leather coat, showed me into his office

“Cold enough for you?” Mel asked.

“Especially with that wind,” I said, looking around at a room that held only a desk, a file cabinet, a telephone, and two wooden chairs.

“Not outside,” said Mel, “I mean in here.”

That’s when I realized that the old house had very little heat and that I could see my breath in the air.

“As you can see, we’re still kind of setting things up,” Mel apologized.

All I really saw was that Coleman Natural Beef was still little more than the dream of the man sitting in front of me. But with a youthful exuberance that belied his 61 years, Mel began explaining his dream.

NATURAL BEEF, he said, was much more than just a value-added product. If it caught on with consumers, it could better the environment, further conservation, and shift the emphasis of beef production from feedlots and grain back to where it belonged — to ranches and grass. It could also help preserve both open space and the ranching way of life.

That was pretty heady stuff, coming from a rancher in an unheated office in Saguache. Yet Mel believed every word that he said, and he knew he was going to help change agriculture for the better.

I kept in touch with Mel and Polly, writing occasional articles and watching how their effort to build a natural-beef business took them on a roller coaster of ups and downs. When they finally enjoyed increasing sales and favorable national publicity, it came too late to head off foreclosure on a big piece of the Coleman Ranch in 1988.

Although devastated, Mel and Polly never lost their faith in natural beef and what it might do for agriculture. When most other folks would have called it quits, they hung on and by 1990 had turned the corner.

With natural beef sales now far exceeding the production capacity of the Coleman Ranch, Mel began enlisting other ranchers to raise cattle under his drug-free guidelines.

Not being a corporate-executive type, Mel didn’t know how to take the company further.

But he did know that to make a difference in agriculture, Coleman Natural Beef needed much higher sales volume, more capital, executive expertise, new ideas, and more effective marketing. He got all that, but only by taking in outside capital, losing control of the company, and stepping down as president to become chairman of Coleman Natural Meats, Inc. In many ways, that worked out fine, for it gave Mel a chance to devote himself full-time to the aspects of the business in which he excelled — public relations and promotion of natural-beef ranching.

By 1996, Coleman Natural Meats dominated the growing natural-beef market, and Mel Coleman was one of the best-known ranchers in the United States. His photograph and comments were printed in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, and major business magazines. He appeared on radio and television talk shows, sat on university discussion panels, and addressed groups that represented everyone from beef producers to radical environmentalists. Sure, he pushed natural beef — but he always ended up talking about land, grass, water, and preserving the ranching way of life.

So what did Mel Coleman really leave behind? From a business standpoint, the obvious things were a company that now grosses $70 million a year, firm financial footing for the Coleman Ranch, and renewed consumer respect for beef — natural or otherwise.

But Mel left behind even bigger things. He proved that alternatives do indeed exist, and that things can be done differently, and often for the better, even in such grassroots industries as ranching that historically have resisted change.

Ever since barbed wire and European cattle breeds arrived in the West, ranchers had few choices. They either earned a profit in the regular cattle market and kept ranching or, if the profits weren’t there, they sold out or faced foreclosure. During the 1970s and 1980s, thousands of ranchers around the country got out of the business and moved to cities and suburbs, while their land often ended up in the hands of developers. The big losers were rural life and open space, two of the most desirable and appealing elements of the West itself.

Mel Coleman had his share of detractors, from vegetarians and animal-rights activists to those who simply resented his success. The latter saw him as a guy with a big hat and big grin who happened to sing the right song at the right time, and they saw natural beef as a gimmick that would never make a difference in anything.

BUT TODAY, the numbers say otherwise; more than 700 ranchers in 17 western states have joined Coleman Certified Ranchers, a network that raises, without the use of growth-promoting drugs, a half-million cattle on tens of millions of acres of rangeland. Many of these ranchers remain in business only because of the premium prices they receive for their natural-beef cattle. And that adds up to a big boost for the economies of small, rural towns, and the preservation of a lot of open space that might otherwise have been cut up for 35-acre “ranchettes” and suburban sprawl.

These numbers relate only to the production of Coleman Natural Beef, which now supplies roughly half the national natural-beef market.

Add in the other companies that are copying Mel Coleman’s approach to beef production, and the numbers double.

In the end, Mel Coleman did a lot of the things he said he was going to do, and they went far beyond natural beef itself. He did indeed made a difference in agriculture, and in doing so helped preserve a bit of the West’s rural life and the open space that he so loved.

So the “end of the trail” doesn’t really apply to Mel Coleman.

His legacy lies in leaving a better trail ahead.

Stephen M. Voynick lives in Twin Lakes. Among his many books is Riding the Higher Range: The Story of Colorado’s Coleman Ranch and Coleman Natural Beef, published in 1998.