Column by Hal Walter

Mountain Life – November 2006 – Colorado Central Magazine

THE BLACK COWS arrived as only these cows could, stepping timidly out of the trailer and putting their heads down to the fresh grass. The weathered rancher told me he had kept them penned overnight before delivering them so they would not hit the ground running when we turned them out.

A few days before, I had written the biggest check I’ve ever signed to Virgil Lawson for nine Maine-Anjou/Angus cows, five with calves — a total of 14 head. It should be explained that the draft for $11,400 was not out of my own personal account but rather the account for the ranch I manage. Nearly everything I knew about cattle was written on that check.

The cattle grazed calmly in their new surroundings. We watched them for some time and talked. The day was sunny and a few small puffy clouds drifted by. Finally he said with a twinge of sadness, “I suppose they look better up here than they did on my place.”I almost felt guilty for buying them.

“You’ll never lose money if you buy the good ones.”

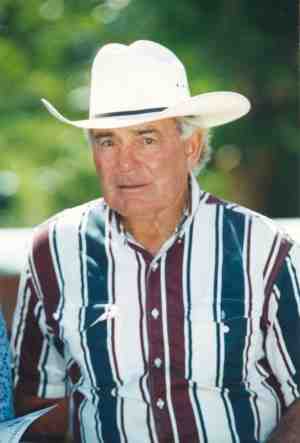

He was born in a cabin in Babcock Hole near Wetmore. His parents, Clyde and Mary, operated a sawmill there and the lumber was hauled out on a wagon over the back roads to Pueblo. By the time the doctor arrived from Florence by horse and buggy on Sept. 29, 1926, Virgil had been born and all there was to do was fill out the birth certificate.

His parents later purchased a dairy near Greenwood, where in addition to dairy cattle they raised grain crops on the hardscrabble farmland that sloped southward off Low Back ridge. Virgil milked cows as a boy and went to school in Wetmore at what is now the Wetmore Community Center. He continued to operate the dairy for many years, branching out from Holstein to Ayrshire cattle.

He and his former wife Evelyn raised three sons, Virgil Jr., Randy and Rick, and a daughter, Cindy. Later in his life, he and Denise Dalton had a daughter, Ashlee.

I first met Virgil in 1984 when I moved to Wetmore. I stopped by his ranch to inquire about buying some hay.

I was awestruck when he picked up a bale by grabbing both strings in one hand, and tossed it into the bed of my truck like a big loaf of bread. It was the first of hundreds of bales I would buy from him, and the beginning of a rare friendship.

I was always impressed by his dedication to agriculture, and his interest in all types of livestock, especially paint and quarter horses, cattle and sheep. Around the Lawson residence there was never any shortage of prize ribbons and trophy belt buckles and saddles, mementos from rodeos and livestock shows ranging from county and state fairs to national and world horse events.

Over the years Virgil seemed to be a permanent fixture in perpetual motion on the area’s highways, hauling horses here, cattle there and hay everywhere. Here was a man who truly loved his work.

“It’s better to get where you’re going on a slow horse than go to the hospital on a fast horse.”

Years ago I was driving home from Pueblo late one spring night and saw Virgil’s pickup truck parked alongside the highway. A flashlight twinkled out in the field. He was irrigating. I owed him some money for hay and so I pulled over and waited. Soon he appeared.

I wrote out the check on the hood of my pickup and he asked, “How’s the jackass business?” I told him I was looking to find a faster one. He said, “I have one you might want to look at. Follow me over to the barn.”

Before I knew it he was driving away and I got in my pickup and drove after him. At the barn he flipped on the lights and in the main paddock stood a nice-looking lineback gray gelding burro. We looked him over.

“I think he’s even broke to ride,” he said. “Jump on.”

I did so without thinking and had no sooner landed on the animal’s bare back when Virgil commenced to haze the burro around the paddock. Somehow I managed to grab some mane and stay on, but we both nearly fell down from laughter after I dismounted.

A few days later I got a call from Virgil. The burro had tried to kill one of his calves. “If you want that donkey come on down and get him.”

“It doesn’t cost any more to feed a good one than it does a bad one.”

A few years later I decided to sell that burro. I stopped by Virgil’s ranch one day because I wanted to make sure that was OK with him. Virgil pulled up a seat on the tailgate of his pickup truck, and after I explained the situation to him, he simply said: “Sell him.”

This was followed by a friendly lesson about how when someone offers the right price on livestock, you sell. In fact, a guy from Missouri had just offered him $25,000 for the stud horse in the corral behind him and he couldn’t turn that kind of money away. This was the real stock market.

All through this conversation his daughter Ashlee played with some baby rabbits. He turned to her and told her to go get her mare. “Ashlee wants to get another colt out of that stud before he’s gone,” he said.

By and by, Ashlee and Frank, Virgil’s hired hand at the time, led out a mare and a month-old colt. Virgil explained that you can breed the mare back at eight days after she foals, or at about 30 days. The colt was around 30 days old.

I followed them all into the barn. There was a big central corral with gated paddocks on either side. They locked the stud in one paddock, and then Virgil led the mare with the foal into the big area in the middle to let the stud check her out over the gates.

The stud acted a little crazy and made some noise. Virgil walked the mare over to the stud. The stud snorted and sniffed over the gate, and then nibbled lightly on her neck. After a while, Virgil led the mare to the other side of this main corral, and walked her into the little paddock with the foal following. Then he circled the mare back out into the main area and shut himself and the foal inside the little paddock, where he stood holding the rope through the gate.

“OK, Frank, let him out,” he said.

The stud walked over to the mare, stepped around her, sniffed her, nibbled some more on her neck. There was some squealing and snorting. Some more strutting around. This went on for a good long while, as Virgil quizzed Ashlee about exactly what day the colt was born, and said that the timing just didn’t seem right.

“Animals know,” he said. “They know better than we do.”

In the end, it was pretty clear the stud wasn’t interested in Ashlee’s mare on this particular day. Finally, the horse just walked off.

As they put the mare in the paddock with her baby and chased the stud back into his pen, Virgil said: “You see, Hal, this stud is so smart, he won’t waste a drop of semen unless he knows that mare is ovulating.”

“In the springtime, it’ll blow and blow and blow, until it snows.”

Last fall I hired Virgil to haul the cattle we bought from him to their winter pasture in Avondale. He leaned on a stick and looked at the cows and calves in the old ramshackle pole corral, his trailer backed up to my makeshift loading chute of portable steel corral panels. His back was sore and he was bent over in pain.

“Let me think a minute about how we’re going to do this,” he said, sizing up the cattle. In a few moments he came up with a plan for sorting the animals and loading them in the trailer.

There was a scary moment when we had trouble getting the center gate shut, but everything happened just the way he said it would and the cattle were loaded and on the road in about 15 minutes flat.

“You learn more from listening than you do from talking.”

When one of the black cows was struck by lightning this past summer, it was Virgil’s idea that we contact the insurance company. The next thing I knew I was hiking up the hill with a shovel, a revolver and a digital camera to get a photo for the insurance agent. Expecting a bear, I found only a sea of maggots and the stench of rot and ammonia. Nothing with claws had eaten on the carcass or disturbed it.

The insurance people wanted a photo of the eartag to positively identify the dead cow. Unfortunately that ear happened to be on the side of the cow contacting the ground. I pried the head up with the shovel and not only was there no eartag but there was no ear at all. Strange, thumb-sized bugs, orange and black and fuzzy, crawled out of the carcass.

I decided to take a photo anyway to show the eartag was missing. I set the shovel down and took a slow step toward my camera, which was resting on a nearby rock. The next thing I knew my feet were tangled with a chunk of wood, then they were above my head and I was suspended in the air. It was a rough landing, but luckily I avoided the carcass.

Apparently giving me an A for the effort, the insurance company paid off on the lightning-struck cow. I called Virgil to tell him about the first promise of money we’d seen since getting in the cattle business, and to give him the opportunity to chuckle at my clumsiness. It was the last time I spoke with him.

“I’d rather be lucky than good.”

Virgil Lawson died on Sept. 27, 2006, just two days before what would have been his 80th birthday. On that golden fall day he apparently had a heart attack while working at his ranch. He was buried a week later at the New Hope Cemetery near Wetmore, not far from his ranch, his family, his livestock. I would venture more than 200 people turned out to say good-bye at the cowboy-style service complete with riderless horse. Ashlee read a poem she wrote about her father and there weren’t many dry eyes in the crowd. It was sad to say goodbye but I am thankful for the time he took with me, the things I learned from him, and all the great stories he told me over the 22 years I knew him.

“The only thing wrong with that bull is he’s red.”

The original herd of 14 head of black cows and calves I bought from Virgil grew to 23 head this year, minus the one that got struck by lightning. They’re fat and shiny, and hopefully we’ll have another 11 calves next spring out of Virgil’s son Randy’s red Angus bull, thanks to a deal Virgil helped arrange.

I’m not sure the cattle really look any better up here than they did on his place. But whenever I check on them I think of the old guy who sold them to me. I hope he’s smiling down on these good black cows.

Hal Walter cultivates a family, livestock, and prose from 35 acres near the ghost town of Ilse in the Wet Mountains.

Memorial contributiions may be sent to the Virgil Lawson 4-H Memorial, c/o Rocky Mountain Bank and Trust, P.O. Box 579, Florence CO 81226.