Article by Steve Voynick

Transporttion – August 2002 – Colorado Central Magazine

Independence Pass is one of those places that varies radically in the eyes of its beholders. Most folks seem to either love it or hate it. Many Lake and Chaffee county locals love the pass because it’s a fast summertime route to Aspen and the Roaring Fork Valley. But tourists tend to be divided: some love it as the scenic high point of their Colorado vacations, while others curse it as a never-to-be-driven-again death trap replete with altitude sickness, blind curves, and dizzying drop-offs. Since the pass is notorious for serious automobile accidents, law-enforcement officers hate it. But the pass also brings in tourist dollars, so many Lake County business people love it.

Who’s right?

Oddly enough, everyone is.

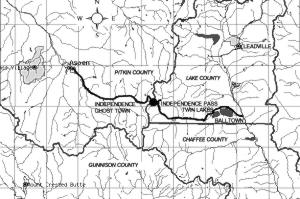

At the lofty elevation of 12,095 feet, Independence Pass is North America’s highest paved crossing of the Continental Divide. The pass itself is the high point of a section of Colorado State Highway 82 that locals call the Independence Pass Road. It’s a twisting strip of asphalt that links the laid-back Lake County village of Twin Lakes with the jet-set community of Aspen, the seat of Pitkin County, which is 32 miles to the west.

Those who love the Independence Pass Road see it as an ever-changing panorama of national-park-quality mountain scenery, with dark conifer forests interspersed with aspen groves, whitewater creeks, waterfalls, soaring cliffs, flower-filled meadows, alpine tundra, and an abundance of elk, mountain goats, and mountain sheep.

But those who hate the pass see only its steep grades, tight turns, spring and fall storms that turn the road into a sheet of ice, and thousand-foot drop-offs with no guardrails over which more than a few cars have plummeted. Those who disdain the pass shudder at the heavy summer traffic which mixes freaked-out flatland drivers pulling campers at 15 miles per hour with impatient tailgaters in Lake County pickups and Pitkin County Porsches for whom double-yellow lines mean nothing.

This love-hate affair with Independence Pass has been going on for more than a century. When U.S. government surveyor Ferdinand Hayden mapped the pass in 1873, it was known as Hunters Pass and was of little significance. The gold camp of Oro City and Granite were far to the east, while the unmapped country to the west belonged to the Utes.

But Hunters Pass started drawing attention in 1879. By then, Oro City had been replaced by the booming silver camp of Leadville. On July 4th of that year, Leadville prospectors struck gold a few miles west of the pass on Hunters Creek at a site they named Independence. Weeks later, prospectors descended an additional 12 miles along Hunters Creek to discover silver at a site they named Ute City, in honor of the owners of the land on which they were trespassing.

By August, burros were packing sacks of rich silver ore back across Hunters Pass and on to the Leadville smelters, where merchants were already preparing for the lucrative business of supplying what promised to become a booming mining industry along Hunters Creek.

But in September 1879, news of the Meeker Massacre 100 miles to the northwest delayed development plans. Fearing a major Ute uprising, prospectors and miners fled back across Hunters Pass to the safety of Leadville, but not before changing the names of Ute City to Aspen, Hunters Creek to the Roaring Fork, and Hunters Pass to Independence Pass.

Several hundred Leadville miners spent the winter of 1879-1880 outfitting for a spring rush to the Roaring Fork country via the shortest route — Independence Pass. From Leadville, a good wagon road led 22 miles southwest to Twin Lakes, then a growing town of 200. From there, the first wave of miners headed for Independence Pass in February 1880, traveling on 12-foot-long Norwegian skis or Canadian-style webbed snowshoes.

A month later, the newly formed Twin Lakes, Roaring Fork & Grand River Toll Road Company, funded by Leadville merchants, began constructing a wagon road west from Twin Lakes along Lake Creek. By May, the toll road had reached the confluence of the South Fork of Lake Creek, eight miles from Twin Lakes, but still short of the pass by eight miles and 2,000 vertical feet of far more difficult terrain.

On May 12, the Leadville Chronicle provided the first description of Independence Pass: “… the ground is either boggy or sloppy, full of rough boulders, or characterized by the general rough surface that renders it practically impassible to man or beast…. On the range the snow is very deep yet, and where the snow has melted there is no way of avoiding the mud, which in places is up to one’s knees….”

Nevertheless, the first wagon crossed Independence Pass on May 25, 1880. Four mules pulled that wagon over a pack trail to timberline at Mountain Boy Park, the last level ground before the final, steep climb to the summit. Freighters then disassembled the wagon and loaded the parts onto sleighs which mules hauled over the pass. The wagon reached Aspen a week later, where it went on public display before being rented out at $20 per day.

Independence Pass was a love-hate affair from the very beginning. The Leadville merchants who reaped enormous profits by selling their goods in Aspen loved it, while the freighters and travelers who had to traverse the pass hated it.

Although the toll-road company made little additional progress during 1880, an erratic flow of foot and pack-animal traffic continued to cross the pass throughout the winter. For these westbound travelers, Mountain Boy Park, elevation 11,200 feet, afforded the last chance to get warm and buy a meal. It was also the last place to buy hay and oats at the exorbitant price of ten cents per pound for pack animals before crossing the summit and descending to the mining camp of Independence.

Although Mountain Boy Park was just six trail miles from Independence, the journey was a true test of endurance that sometimes became a matter of life and death. For much of the way, a single line of traffic plodded through a narrow trench between eight-foot-high walls of snow that were rarely wide enough to allow pack animals to pass each other. Depending upon weather and traffic, covering these six miles could take several days. During the winter of 1880-1881, more than 100 pack animals attempting to cross the summit became so weakened by exertion, cold, and lack of feed that they had to be shot.

In March 1881, the owners of a Leadville bakery made the mistake of trying to haul a large iron oven on a six-mule sleigh to Aspen. For four days, the overloaded, slow-moving sleigh blocked the summit trail, and a two-mile-long string of pack animals trailed behind it, unable to pass. Finally, two miles west of the summit, a group of irate freighters threatened to shoot the oven’s owners unless they cleared the trail immediately. Fearing for their lives, the owners pushed their iron monstrosity into a snow bank and abandoned it. Broken and rusted, it remained by the side of the trail for decades as a landmark called “The Big Oven.”

Spring mud could be a worse impediment than winter snow. When overloaded wagons bogged down in mud, teamsters lightened their loads by throwing out as much of their clients’ cargo as necessary — until the trail was littered with abandoned goods. Whenever that happened, scavengers left Twin Lakes with empty wagons, filling them as they went, then selling their salvaged cargo in Aspen at boom-town prices.

Thanks to the labor of 250 men, the Twin Lakes, Roaring Fork & Grand River Toll Road Company finally opened its Independence Pass Toll Road to through traffic on November 1st, 1881. The company’s initial round-trip rates from Twin Lakes to Aspen were $1 for a pack animal, $6.50 for a double team, and $9.00 for a four-horse team, payable in installments at five toll gates.

Sixty Aspen-bound wagons per day immediately began crossing Independence Pass, and two express companies carried passengers on regularly scheduled stages between Leadville and Aspen. These were not Concord-type coaches with their relatively soft suspension systems and dangerously high centers of gravity. The Independence Pass stages were modified freight wagons outfitted with wooden seats and canvas siding draped over wooden frames. While not affording the comforts of Concord coaches, the wagons were far safer on the steep grades, tight turns, and very rough road.

But a mere week after the toll road’s opening, snow forced teamsters and stage drivers to switch to heavy sleighs. To keep the road open, shovel brigades on both sides of the summit labored mightily to clear away the deep snow deposited by frequent drifting and almost daily avalanches.

Eastbound wagons usually hauled hand-cobbed silver ore containing several thousand ounces of silver per ton. When road conditions were bad, teamsters continued to work by hauling wagon loads of ore as near to the pass as possible, caching it, then returning to Aspen for more. When the summit finally became passable, they retrieved their cached ore and completed the job of hauling it to the Leadville smelters.

When ore thieves began raiding the caches, Lake and Pitkin counties posted rewards for information leading to their arrests. But the rewards were never claimed. Instead, justice was meted out along the Independence Pass Road, where at least three ore thieves caught in the act were summarily shot to death.

In a newspaper interview in January, 1935, former freighter John Borrel recalled his last crossing of Independence Pass exactly 50 years earlier. “It was the dead of winter and snow had been falling until it was ten feet deep,” he said, describing a round-trip between Twin Lakes and Aspen that took 14 days and nights. “Although traffic was heavy, the snow drifted so badly that the road was not kept open. We were near the top of the range for three days and nights in a traffic jam. Someone got stuck in the snow, teams began to line up, unable to pass, until they reached in both directions for a great distance. We finally cleared the jam by carrying sleds, stages, and wagons and their loads out of the road and to new positions. It was mighty labor and we were all exhausted.”

Borrel also recalled that brakes often couldn’t hold the heavy loads on the steep downgrades, and if a horse in a team of six fell, it would be dragged hundreds of feet before the wagon could stop.

A stage passenger described his crossing in April 1886. “We started to make Independence Pass in two four-horse sleighs and encountered one of the most terrible wind and snow storms the driver had ever seen,” he recounted to a Chronicle reporter. “The snow was blinding and the wind cut like a knife blade and we found our passage impeded by extensive slides. For a time we thought we would perish from the cold, which was simply excruciating, and the poor horses suffered more than the men. We unhitched the horses at the pass, abandoned the sleighs, mail, and baggage, and tried to make our way through the deep drifts. That was impossible, so we sent one man down to the [Mountain Boy Park] toll gate for men and shovels. In the meantime the lead horse began to flounder and finally went over the precipice. He slid about 500 feet when he struck a tree breaking his back completely. The driver climbed down to the poor animal but found it already dead. We walked, rolled and tumbled down the m

The Twin Lakes, Roaring Fork & Grand River Toll Road Company had improved the Independence Pass Road so much by 1886 that summer travel between Twin Lakes and Aspen took as little as 10 hours. But that was the last full year of travel over the pass, for railroads (the Denver & Rio Grande, soon followed by the Colorado Midland) finally reached Aspen in September of the following year. On October 24, 1887, the final stage crossed Independence Pass and the toll road was abandoned. Noted the Chronicle, “Thus another relic of the early days gives way before the great civilizer, the iron horse.”

Dwindling numbers of freight wagons continued to cross the pass in summer on the deteriorating old toll road, but traffic virtually stopped after 1893, when the silver-market collapsed and closed the Aspen mines. In 1911, when Colorado established State Highway 82 from Glenwood Springs to Aspen, there was no reason to extend the highway east over Independence Pass to Lake County.

But slowly increasing numbers of automobiles and trucks renewed interest in a highway linking Lake and Pitkin counties. In 1927, the Colorado Highway Department opened an eastern extension of State Highway 82, a graded, gravel automobile road crossing Independence Pass that was built, in part, atop sections of the old toll road. Open only during the summer, the new Independence Pass Road eventually became popular as a tourist attraction.

But the Independence Pass Road might still be gravel today had Aspen not developed into a major tourist destination in the 1950s. Because the pass route was significantly shorter than the Denver-to-Aspen drive via Glenwood Springs, the road was widened where possible, rerouted in a few places, and paved in 1967. This is the road that exists today.

Unfortunately, road-building efforts of the 1920s and the 1960s did some lasting environmental damage. The biggest eyesores and problems are associated with the “Top Cut,” the 1.5-mile-long grade below the west side of the summit where blasting and blading has created an orange gash of erosion visible for miles.

Because the Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) had its hands full just maintaining the Independence Pass Road, Aspen biologist and educator Bob Lewis established the Aspen-based Independence Pass Foundation (IPF), a nonprofit, volunteer group dedicated to reversing the environmental degradation and improving the safety of the road west of the summit. Since its founding in 1989, IPF has already spent $2 million, acquired through donations and grants, to build retaining walls, stabilize eroding slopes, remove summit snow fences that damage alpine tundra, and replant hillsides. IPF is now raising another $1.6 million to fund a five-year project to restore and stabilize eroded areas along the Top Cut.

But in Lake County, where the economic picture is considerably less rosy than in Pitkin, concerns about the pass focus not on environmental restoration, but on economic benefit. Average daily traffic volume over Independence Pass is now a record 1,200 vehicles per day. Some 180,000 vehicles therefore travel the Independence Pass Road during the five months it is open each year. All pass through Twin lakes and many through Leadville, where their occupants leave behind respectable numbers of dollars at gas stations, restaurants, motels, and historic attractions.

Of course, these economic benefits could be considerably greater if the pass were open year-round. That hasn’t happened in 116 years, but it stands to reason that if brigades of men wielding snow shovels could keep the pass open during the winters of the 1880s, then CDOT’s heavy, diesel-powered snowplows should certainly be able to do the job today.

Several years ago, State Senator and Leadville resident Ken Chlouber proposed just that. But CDOT wasn’t interested in shouldering the additional and substantial costs necessary to keep the pass open.

“CDOT then had enough in its budget, which is not the case today,” Chlouber says. “But we keep high passes open all over this state, so why not Independence?

“Independence Pass has huge potential as a winter recreational site for snowmobiling, cross-country skiing, snowshoeing, and sightseeing,” Chlouber continues. “And a growing population is creating more pressure to utilize these areas. I can’t say when it will happen, but I guarantee that some day Independence Pass will be open year-round.”

Lake County Undersheriff Herschel Blackford thinks differently. “C’mon,” Blackford says, “You’re talking about deep snow, blizzards, whiteouts, and avalanches, all mixed in with steep grades and tight turns. You start putting tourists up there in January, tourists who don’t like to drive mountain roads even in the summer, and all you’re going to get is lots of trouble and expense.”

State Representative Carl Miller, also a Leadville resident, takes the middle road. “Because of its economic impact, I’d like to see the pass open year-round,” says Miller. “Unfortunately, that’s just not practical. But I do think CDOT should open the pass earlier and close it later, conditions permitting, and not lock into traditional opening and closing dates. This year is a good example. The pass opened on May 24th, but with the dry spring, it should have been opened three weeks earlier.”

Nowhere is the opening-and closing-of Independence Pass felt more profoundly than in Twin Lakes. “It’s like night and day,” says June Hervert, owner of the Twin Lakes General Store. “I keep this store open all year because it’s also the Twin Lakes Post Office. But I literally do 99 percent of my business in the five months that the pass is open.

So does Hervert, who probably stands to gain more at the cash register than anyone, want to see the pass open year-round?

“No,” she says, after a moment of thought. “To make the pass truly safe for winter travel, the state would have to spend millions building avalanche sheds, installing guard rails, and widening the road. Since that’s not likely, it’s better to leave the pass open five months each year, just the way it is now.”

“Just the way it is now” is pretty much the way Independence Pass has always been, at least since 1887. It’s a spectacularly beautiful, admittedly dangerous, summertime-only, high mountain pass that folks either love or hate.

Steve Voynick lives in Twin Lakes at the eastern foot of Independence Pass.