By Ann Marie Swan

Life has a way of moving us along, and it’s taken me far from my hometown, New Orleans. This surprises me because I always assumed I’d be back home by now, taking my place in this city of misrule.

I adore New Orleans. It’s a mixed bag of excitement and heartbreak, lovely yet exasperating. At times, it feels like urban transcendence despite deep pockets of poverty and crime.

New Orleans has that rich, earthy smell of a place in a constant state of decay. The swamps try to reclaim the city, seeping up through it, buckling her sidewalks and roads.

It’s a place where lineage is casually traced by the question, “Who is your mother?” A place where manners are so important, it’s a means of natural selection, pinning participants on the evolutionary scale.

New Orleans is a city that values its writers. Maybe not monetarily, but with some regard and that occasional round of drinks. The lost art of conversation is treasured there. It’s a celebrated skill.

My hometown is a city for the senses. It’s enticing with its luscious food, music and art. Visitors marvel at the plethora of stages at Jazz Fest and enjoy the fragrance of spring as they walk in the shade of live oaks.

It’s so enchanting, they actually believe they have what it takes to live in this city and make it their home. That is, until the summer heat becomes oppressive, their car is brazenly stolen or they end up nursing a friend who was robbed at gunpoint. These short-lived transplants don’t understand the emotional stamina the city requires of its denizens. New Orleans needs and takes everything. Her people are long-suffering.

New Orleans remains its own category. For me, it’s a place of well-worn comfort where I understand social nuances and what’s expected of me.

Beyond the physical locale on the Mississippi River, home is my family there. I return when I can to see my parents. As I’ve lived and worked in other parts of the world, it became more challenging over the years to get home. It was a place I couldn’t seem to visit enough. New Orleans became a point of self-reflection, a collision of past and present, where I measured who I am against what I imagined for myself.

I’ve pitched the move to New Orleans many times, but my family doesn’t bite. It’s fun for them but they wilt and wither in the heat. I’ve punched the numbers and looked at my daughter’s school curriculum, wondering whether we could live in two cities.

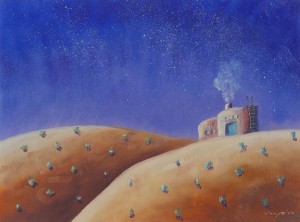

This plan isn’t reasonable, so home has transformed into a longing. This longing has expanded, taking on a devotional quality and its companion, grief.

Now that I’m settled in Salida, intent on raising our daughter here, the longing takes on new sensations. Sometimes it throbs. Other times it’s a dull ache. Home becomes out of focus, like a long-ago, fuzzy memory.

I was born a fourth-generation New Orleanian. In a sort of mass human migration in the ‘80s, my peers and I moved away. We sought adventure and employment as the oil business slumped, its misfortune rippling through the bayou country. We also wanted solace from the crack years that ruled the city, poisoning the bodies and minds of so many. Weary of being fearful of crime, we shared stories of close calls as young black men killed other young black men.

After all these years and the misery that was Hurricane Katrina, how to get back? How to satiate this longing? How to truly love winter in the Arkansas Valley when it seems to last through May? What does it mean to be home anyway?

My fingertips become numb in the schoolyard as I consider this. Why can’t I be completely serene in beautiful Colorado? My daughter, who has eked out every opportunity to play here with friends, wanders over. As the sun dips below the mountains, she slips her hand into mine and says, “Let’s go home.”