THE GENTLE ROLLING HILLS JUST SOUTH OF Cañon City are covered with the green that a semi-desert landscape can produce: low grasses, cactus, shrub-like pine and juniper trees. Ground and surface waters drain northeast from the Wet Mountains immediately adjacent, though surface waters flowing through the area, like Sand Creek, tend to appear only following substantial rainfall.

Oak Creek Grade Road winds south from Cañon City and within a few miles climbs into the Wet Mountains, eventually reaching Westcliffe to the southwest. Just east of Oak Creek Grade a couple miles south of Cañon City lies the site of the former Cotter uranium mill, a Superfund site since 1984. The large sign that marked the entrance when the mill was operating is long gone. There is only a small sign now with vague wording suggesting little about the site’s past: “Former Cañon City mill remediation project.” There is nothing about uranium, radioactivity, environmental contamination, the fact that it’s a Superfund site or seemingly never-ending process of trying to get the site cleaned up.

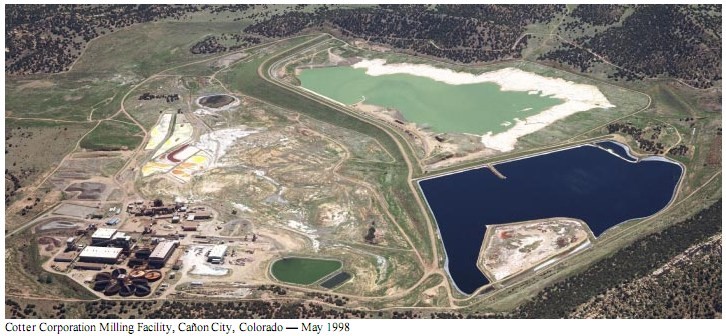

(Photo courtesy of Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment)

The Cotter Corporation uranium mill was established in the late 1950s by a group that included Manhattan Project research chemist David Marcott and two oilmen. The original uranium mill opened in 1958 and could process 72 tons of ore per day. Uranium milling crushes the rock in which uranium is found. Chemical and drying processes are then used to extract the uranium and ultimately produce a dry powder called yellowcake (uranium oxide). Yellowcake is then shipped to facilities in other states for refinement into nuclear fuel. Yellowcake is radioactive, and so are the mill tailings that are left behind.

The Cotter uranium mill site’s long strange history is still adding new chapters today. Established during U.S. postwar efforts to find “peaceful” uses for the atom, the uranium mill was, by the early 1970s, found to be the source of substantial radioactive and heavy metal contamination in area soils and waters. One of the first indications of the contamination was an illness among cows in the area caused by exposure to molybdenum, one of the byproducts of milling uranium. Other milling byproducts include radioactive decay products from the uranium, including radium plus heavy metals such as lead. Radioactive radon gas is also a byproduct of the process.

Economic problems for the mill began in the 1960s when the federal Atomic Energy Commission (now the Nuclear Regulatory Commission) ended its exclusive contract with Cotter and authorized uranium mills to produce for the open market. Cotter subsequently purchased the Schwartzwalder uranium mine near Golden to ensure an in-house supply of ore, which had to be trucked to the mill from more than 100 miles away. But economic problems continued for the mill, even after Cotter acquired and processed 100,000 tons of Manhattan Project waste – highly radioactive waste from the manufacture of the country’s first atomic bombs.

The shipping in of waste for reprocessing raised fears in the community that the Cotter site would become a dumping ground for the nation. A threat in 2002 to bring in radioactive waste from New Jersey, fought by the community and a newly formed group Colorado Citizens Against ToxicWaste (CCAT), signaled the beginning of the end for the mill and tailings impoundments. The company decided in about 2010 to permanently close and dismantle the mill, initiating the long, complex process of working with regulators to determine the ultimate cleanup for the site.

Over the years there have been multiple lawsuits filed against Cotter, alleging property damage and health problems. There was also an investigation by the state, and a variety of radioactive materials license violations. The mill operated off and on, depending on the uranium market, until 2006. Following the decision to close, most buildings, facilities, equipment, and other materials were dismantled and disposed of in the Primary Impoundment.

The environmental disasters began with Cotter dumping contaminated mill tailings on bare ground at the mill site and were exacerbated by a major flood in the area in June 1965, which brought contamination from the mill site into parts of the Lincoln Park neighborhood. Over the years both flood waters and groundwater that flow generally north and northeast from the site led to the contamination of soils and private water wells in Lincoln Park. Wells that were used for domestic use plus watering gardens and livestock could no longer be used. Cotter was forced to construct new lined tailings impoundment ponds in the late 1970s. Also during the years the mill operated, intense winds carried contaminated mill tailings hundreds of feet in the air which were blown miles from the mill site, generally to the east toward the small town of Brookside and no doubt beyond.

An often-overlooked fact about the Cotter uranium mill is that it should never have been located where it was: uphill from a community and significant orchards and other agricultural production, and upstream from a major river, the Arkansas. There was no significant uranium ore within about 100 miles; and it was built on ground which had been extensively mined for coal from the 1890s until about the 1930s, leading to suspicions that contamination may have found a “deep path” toward the Arkansas River through the coal mine workings. The uranium mill was an environmental disaster waiting to happen.

Infamous industrial waste disasters around the country in the late 1970s led to the passage of the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) in 1980. CERCLA is informally called Superfund. The legislation allows the Environmental Protection Agency and state agencies to clean up contaminated sites, and forces parties responsible for the contamination to perform the cleanups or to reimburse for the cleanup work that public agencies oversee. The goals of Superfund are to protect human health and the environment by cleaning up contaminated sites, make responsible parties pay for the cleanup, involve communities in the Superfund process, and return Superfund sites to productive use when possible.

Central Colorado is home to seven of Colorado’s 20 Superfund sites on the National Priorities List, needing further assessment and cleanup: California Gulch in Lake County, the Standard Mine in Gunnison County, the Colorado Smelter in Pueblo, the Nelson Tunnel in Creede, Smeltertown in Salida, Summitville Mine in Del Norte and the Lincoln Park/Cotter Mill Superfund site just south of Cañon City. While other sites are often associated with metals mining, the Lincoln Park/Cotter site was only a uranium mill with no nearby uranium mine.

Over the years there have been stories of significant human health issues in the nearby rural residential neighborhood of Lincoln Park, but occasional limited examination by state and federal agencies have failed to show that the incidence of cancer or autoimmune disease is significantly beyond the expected rate. However, there has never been a comprehensive longitudinal study to examine possible human health impacts from the mill’s contamination of the area.

Today, community members who are part of the Superfund site’s Community Advisory Group (CAG) meet monthly with state and federal regulators plus the current site owner, Colorado Legacy Land (CLL). Community members of the CAG, also referred to as the “CAG-only,” provide substantial historical context to the current regulatory activities. As regulatory staff (and site owners) come and go, community members provide the essential institutional memory regarding the site to ensure that a comprehensive environmental assessment is completed and to guide decisions about the ultimate cleanup.

Approval of the Draft Remedial Investigation Report is expected soon. Once the draft report is approved, CLL will have 60 days to submit a work plan that will detail the environmental testing still needed to determine the full nature and extent of the contamination. A Human Health and Ecological Risk Assessment will be conducted concurrently with the remedial investigation. Ultimately, there will be a feasibility study to determine the best long-term plan for cleanup of the site and nearby neighborhoods. Once the cleanup is completed, the core area of the mill site may be placed under permanent monitoring and ownership of the U.S. Department of Energy if it is viewed as too contaminated for any human use. It is expected, though, that a significant portion of the property will ultimately become available for development or at the very least, open space and trails, as conditions allow. Developers and a land trust are already following the Superfund process at the site, hoping to help determine possible future uses.

Meanwhile, area residents who have followed the saga of the Cotter uranium mill — some since the late 1970s — have one clear goal: to achieve the best possible cleanup of the site, hereby putting decades of contamination and controversy in the rear-view mirror.

Emily Tracy has been an activist regarding the Cotter Mill site since the late 1970s. She chairs the Community Advisory Group for the site and is a Cañon City Councilmember.

When I wrote “Yellow Cake Road” I kept my back up documents because I suspicioned Cotter might want to sue me. After a couple of threats, I placed my documents in the stacks at Florence Historical Archives. They are available (but only with my presence) to anyone who wants to check on facts. Lynn’s original documents were taken, by CUBoulder, to their historical documents at Colorado University in Boulder. Deyon Boughton