by Susan Tweit

After a holiday weekend spent cooking for a house full of visitors from age 10 to 81, I have food on my mind, in particular, ways to lighten the carbon footprint of what we eat. According to Stephen Hopp in Animal, Vegetable, Miracle, agriculture consumes about 17 percent of the United States total energy use, second only, Hopp notes, to our gas-guzzling vehicles.

Producing our food is energy-intensive for three main reasons: the distance it is transported from farm to table – an astonishing average of 1,500 miles, how much processed food we eat, and our energy-intensive farming methods, especially synthetic fertilizers.

It takes a surprising amount of energy to turn whole food like wheat kernels or cows into something “conveniently” packaged and ready to eat, whether a box of crackers that relies on additives like high-fructose corn syrup (which itself is so energy-consumptive it might as well be bottled petroleum, as Michael Pollan points out in Omnivore’s Dilemma), or fast-food burgers.

Producing, transporting, processing and delivering just one cheeseburger (plus its packaging) emits about 2.5 pounds of greenhouse gasses. Since Americans eat between 50 and 150 burgers a year per capita, the greenhouse gas cost of our burger habit is equivalent to the emissions from 6.5 to 19.6 million full-sized SUVs. Ouch.

Researchers Martin Heller and Gregory Keoleian calculate that as much as 40 percent of the energy used in producing our food goes to making synthetic fertilizers and pesticides. Producing and transporting a pound of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer releases almost eight pounds of greenhouse gases into the atmosphere itself.

According to Stephen Hopp, if each of us ate just one meal of locally produced, organic food a week, we would save an astounding 1.1 BILLION barrels of oil a year, many times the amount released so far in the Gulf of Mexico disaster.

I wasn’t thinking of any of that when I planned the organic kitchen garden which allows us to step out the kitchen door and pick whatever is ripe to eat – right now, that’s mixed lettuces in green and red, ruffled and lobed, sugar snap peas, baby beets, chard, strawberries, and the last of the asparagus.

I was only focused on the fresh and beautiful food it would produce, and my intimate connection to that food. Now I appreciate how healthy my garden is for the planet, too.

If you don’t garden, shop at the local farmer’s market or local-foods market, buy a community-supported agriculture share from a nearby farm, or search out neighbors who garden or produce food.

Here in high-desert, short-growing-season rural Colorado, eating locally and organically might seem like a difficult proposition. But as it turns out, it’s not only possible, it’s rewarding – and delicious.

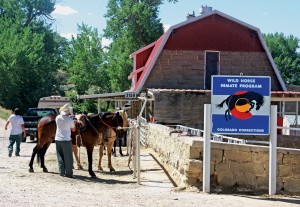

My appreciation to all who produce food in our region, from home gardeners to community farms and ranches, to the aquaculture program at the state prison. Our lives are linked by this web of delicious food and the community of the land it springs from.

Award-winning writer Susan J. Tweit is the author of 12 books, and can be contacted through her web site, susanjtweit.com or her blog, susanjtweit.typepad.com/ Copyright 2010 Susan J. Tweit

Hi, Susan. Although we no longer subscribe I occasionally read CO Central online. Thankfully we are becoming more and more aware of the huge impact our “daily bread” has on our planet. While it’s easy to see pollutants spewing from the exhaust systems of vehicles, industrial plants, and the like it is not at all easy to see the pollution our food system is causing. I am glad to see articles and blogs such as yours as well as books now being written educating people and helping to bring about an increased awareness.