By Jan MacKell Collins

During the 1870s and beyond, people in the eastern half of America were eagerly reading about pioneer adventures in the West. Only handfuls of them actually knew somebody who dared to sell what they could, pack what remained into a wagon, and set out to begin a new life in a raw, untamed and sometimes dangerous land. To those in big cities like New York, Philadelphia and other places, such an undertaking was unimaginable. Some stories read like a juicy dime novel, an especial boon to those living boring, menial lives. The right author could lead readers into an exciting other world, one which they knew little about and found simply fascinating.

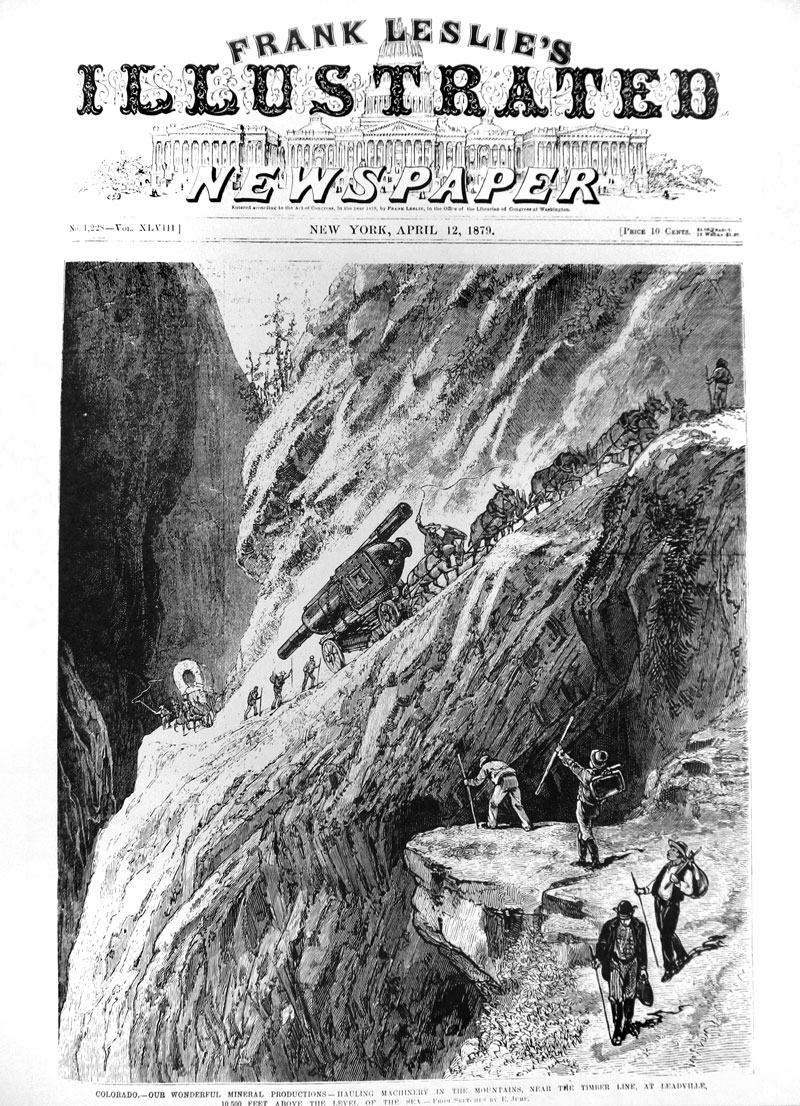

As more and more people went West, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper became one of the most reliable periodicals to provide accurate information about life in and around the Rocky Mountains. In April of 1879, Leslie’s published one of several lengthy articles about Leadville, the newest locale of several mining booms in Colorado. An unnamed writer was accompanied by illustrator Edward Jump, a sometimes sketch artist and photographer who at one time had a studio in San Francisco, among other places. Jump, who had traveled extensively for Leslie’s since at least 1868, was probably living in St. Louis, Missouri when he was commissioned to go to Leadville.

Jump had visited Leadville before, as his sketches of the area had already been featured in an article about the town in February. It is not known whether he knew of precarious Mosquito Pass, which the artist and writer accessed to reach Leadville in April. Jump’s anonymous partner had clearly never been over the pass, writing that “there were moments when my heart beat backwards as the vehicle lurched over a yawning precipice of fathomless depth.”

The men were not alone on the pass; mules dragging mining machinery, other wagons, and plenty of travelers formed an endless line, also headed to the new “El Dorado.” Upon passing through the gulch where mines and miners dotted every hillside, the men reached Leadville on a late Sunday afternoon. The Leslie’s writer called it, “the Mecca towards which all true believing miners are now engaged in making pious pilgrimage.”

Indeed, Leadville was as raw, raunchy and ribald as a boomtown could be. The population was guessed to be around 20,000, mostly miners who fairly swarmed the city each Saturday afternoon and returned to work on Monday morning. “The town was literally writhing with men in the rough but picturesque costume of the mines,” the correspondent observed, “many wearing blood-red sashes around their waists.”

precarious highway leading to Leadville. Courtesy of the author.

From his hotel room window the writer counted eighteen saloons within one block alone. “I could not sleep one wink for the pistol shots,” he wrote, “the miners use their revolvers to express joy, sorrow, anger, surprise.” During the day the crowd, overall, “seemed both good-natured and jovial; almost everybody had money.” Night time was a different matter. “At Leadville, night is turned into day,” the author said. “Miners swarm in the streets, having come in from the mountains to spend their eighteen or twenty dollars at faro, or in the saloons.” Of the 4,000 or so females in town, it was noted that “no woman is safe from insult if she walks about after dark.”

The men were making their money from ore that was proclaimed to be “richer than that at the Black Hills. A miner will drive in his pick and a piece a yard square will roll to his feet, containing sometimes as high as 95 percent of ore.” All around town, some 50 mines were in operation, the top ten being the Little Pittsburgh; Birden, Tabor & Company; Argentine Group; Iron Mine; the Adelaide; the Little Chief; the Double Decker; the Dyer and the Climax. Ore from these and smaller mines were estimated to be worth around $100 per ton. Within five miles of Leadville were over 200 prospect holes, and “new lodes are discovered nearly every day in the week.” Claim jumping was becoming a problem; those staking claims had to make a mad rush to the claims office, lest someone else who knew about it beat them to the punch.

On average, miners were earning four dollars per day. Rent and real estate were incredibly high. Offices rented for ten dollars per month, while a simple store-room rented for as much as $400 per month. Town lots were selling for up to $1,500, but one corner lot passed quickly from owner to owner and soon reached $10,000 in value. Leadville’s population, it seemed, was on the brink of outgrowing itself if building did not continue. Also, “the water in Leadville is so bad that a supply has to be procured from some distance.” The tainted water was blamed for outbreaks of diphtheria, as well as pneumonia.

Clearly, Leadville was bound to be one of the biggest and best-known boomtowns in the West. The writer assured that more articles would be published by Leslie’s by concluding, “Leadville is very wicked; vice in its most civilized and most repugnant form is everywhere rampant.” For his part in the article, Edward Jump sketched out a record of the wild journey over Mosquito Pass, as well as a busy street scene in downtown Leadville.

More illustrations would come in subsequent articles about Leadville through June, showing miners sleeping on the floor of a billiard room for the price of two bits, and the interior of a dance house. It is unknown whether the writer was the same one as the man who wrote about the goings-on in April. The last article, in July, did not include Jump’s work because the artist had quit and was trying to establish his own newspaper in Montreal. When that failed, he moved to Chicago where he committed suicide in 1883. Jump’s passing is sad for more than one reason, for his colorful sketches remain today as an accurate testament to Leadville’s unbridled, bawdy days.

Jan MacKell Collins balances her writing career with building a time machine so she can visit Leadville in 1879.