Essay by Deric Pamp

Mountain Life – December 2005 – Colorado Central Magazine

We walk our dogs, most mornings, in one of several narrow canyons that drain the Arkansas Hills and run down to the flood plain, across the river from Salida. We get there by driving a rough county road that runs only a mile or so to a dead end. The road has few users other than dog-walkers, some dedicated runners, and an occasional beer-drinker who leaves his spoor glinting in the bushes near the road until we pick it up. We recently found that someone had used the road to dump the carcass of a canine: headless, pawless, and skinned, we could not tell if it was a coyote or a domestic animal. Its slim, muscular body seemed naked and pathetic. It had been doubly defiled, stripped of its dignity as well as its coat, then tossed carelessly into the rabbit bushes along a county road. Our dogs found it, of course, but it upset them and they acted very subdued.

This morning we brought a shovel and while Barb took the dogs on a short loop, I buried the body. The ground is stony there, thick with rocks washed down the canyons or eroded off the steep hills directly above, so it was only with some effort that I managed to scrape a foot-deep trench. I moved the body in, then piled two feet of earth on top of it and covered the mound with a good layer of stones. This burial will not defeat someone who really wants that body, but it was the best we could do under the circumstances.

Driving away, Barb and I — and perhaps the dogs, too, although they did not say so — felt much better. The dumping of that canine’s remains seemed so callous and cheap and disrespectful that we felt dirtied by being connected to the act in any way. Burying the corpse was cheering to us because it lent a sense of dignity to the animal’s death and it seemed fitting to return the body to the earth. We wondered if it had been a coyote, “God’s dog,” or a domestic pet that met an ugly end.

In his novels, Tony Hillerman discusses Navajo beliefs about death and dead bodies – how a hogan is abandoned if a person dies inside it, which made good sense when disease was a mystery, and how a Navajo’s body should be treated with respect and then left to the elements. Other tribes had similar views.

I confess that I am not a neutral observer: I wear Navajo “ghost beads,” a necklace of juniper seeds and hematite that protects me from chindi, the malevolent spirits that haunt death hogans. More important, the necklace reminds me of the Navajos’ reverence and appreciation for the beautiful world in which we live. These native Americans’ ideas seem to me much more reasonable than current Western practices. Instead of simply and quickly returning a body to the ecosystem, we fill it full of poisonous liquids, put it on display (sometimes for decades, like Lenin’s corpse), then house it in an expensive casket made of fine wood and expensive metals, then drop the whole package into a concrete sarcophagus before we bury it. What a waste of raw materials, including the carbon and water and what Carl Sagan called “star stuff” contained in the body. What a weird exercise in the name of dignity.

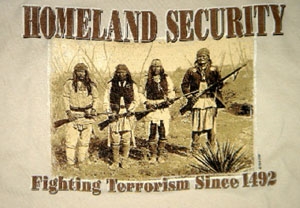

BASED ON DEMOGRAPHICS, it was probably a Caucasian person that left this dog’s body in the weeds, naked and headless and pathetic. Compare that to the native American practice of honoring the animals they hunt, thanking them for the sustenance and materials their bodies provide, giving them dignity in death. Then compare our Western ways to the Navajo practice of meeting the dawn with prayers and reverence, and choosing to live in a place of remarkable beauty that they treat with respect. Some modern Navajos throw beer cans out the window as they drive on the rez, it’s true, but that lazy habit flies in the face of their ancestral teachings to honor the Earth.

We Westerners have only recently started to question our ancestral teachings that all of the Earth and all its animals are here for us to waste and abuse as casually as we wish, leaving much of the world as dry and bare as a mumbled bone. Some of us ask questions about our profligate habits and seek new solutions, but our leaders are hide-bound and narrow of view, proposed that we try to drill our way out of our self-created energy “crisis.” Instead of protecting the Alaskan National Wildlife Refuge or working seriously on alternative energy sources (not since the Carter administration), we are choosing to despoil that magnificent wilderness, and to threaten the animals that live there, for a paltry few months’ supply of oil. We treat the world just the same way that the person who dumped it treated that canine, with little thought and without any dignity.

I wonder which is worse: to sacrifice a pristine wilderness without any reasonable semblance of a national energy policy, or to skin and dump a dog or coyote like a bag of garbage. These acts look much the same to me. Drilling in ANWR while we produce Hummers in four varieties makes me feel dirty.

Among other things, Deric Pamp is a Salida attorney and consultant for non-profit organizations.