Article by Virginia McConnell Simmons

Fort Garland – June 2008 – Colorado Central Magazine

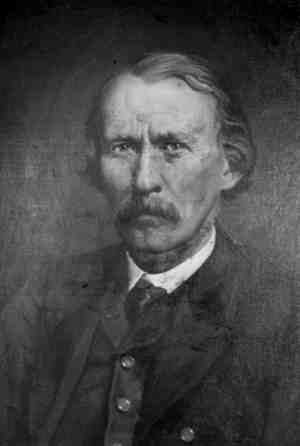

THE MOST CELEBRATED NAME associated with Fort Garland is Kit Carson: trapper, scout, Indian agent, Indian fighter, and Civil War officer. But, in the fort’s quarter-century as a U.S. Army installation, many individuals took part in the life of the old adobe stronghold in the San Luis Valley.

Now, year ’round, the public can visualize military life in territorial days and the early years of Colorado statehood at Fort Garland, the oldest existing military fort in what is now Colorado.

This year, on June 20, 21, and 22, the fort will salute its 150th birthday and long life. For the mud walls to still stand instead of melting into the ground is no small achievement, for which credit is owed to concerned residents of the Valley and to its present owner, the Colorado Historical Society.

After the Mexican War and the acquisition of the American Southwest by the United States in 1848, the U.S. Army took on the mission of protecting travelers and settlers from hostile Indians by creating a network of military installations that fanned out from Fort Union on New Mexico’s plains.

Fort Massachusetts was formally established on June 21, 1852. This rough facility of poles, logs, and adobe bricks was a short distance north of the Sangre de Cristo Land Grant, where small, Hispanic settlements were just coming into existence.

Fort Massachusetts was near a route used by traders, Ute Indians, and other tribes between the Rio Grande and Arkansas rivers, where protection was needed from raids, but the fort proved to be inconveniently located to defend the settlers, travelers, or itself. Nonetheless, during its short life, Fort Massachusetts offered a base for militia who were pursuing hostile Indians after the Pueblo Massacre and support for government surveyors like Heap, Beale, and Gunnison. (The site, on private land, contains no vestiges of the fort today.)

As early as 1856, construction of the larger, better-located Fort Garland was begun on a military reservation leased from the owners of the Sangre de Cristo Grant. Spanish-speaking settlers in the area were hired to produce thousands of adobe bricks and to lay up the walls for the fort.

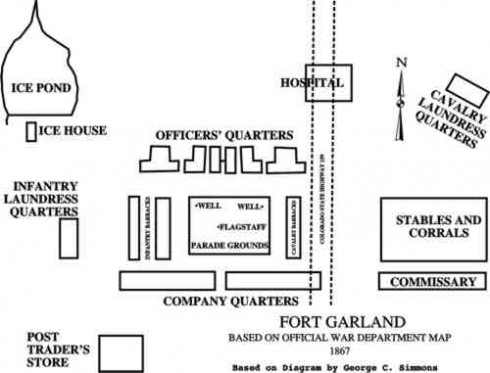

On June 24, 1858, personnel moved six miles south to the new fort. When completed, this facility would consist of long, flat-roofed quarters for officers and barracks for cavalry and infantry, which formed a square around a parade ground, with stables, hospital, laundries, and a trader’s store being located outside. The parade ground, barracks, and officers’quarters still exist and can be visited a century and a half later.

THE MOVE TO Fort Garland coincided with a pivotal moment in Colorado history, for gold had been discovered at Cherry Creek, and the Pikes Peak Gold Rush was about to erupt. Thousands of prospectors swarmed to the Central Rocky Mountains, and Fort Garland, south of most of this activity, was a staging area for prospectors heading to the San Juan Mountains in 1860 and 1861.

Moreover, originally part of New Mexico Territory, Fort Garland found itself in the newly created Colorado Territory in 1861, and even greater change was about to happen.

The Civil War broke out and changed the fort’s role. Volunteer companies assembled at the fort to muster in as regulars in the Union Army. Some took part in the battle at Glorieta Pass, the northernmost engagement with Confederates in New Mexico. New Mexico Volunteers, many of them being Hispaños, were garrisoned at the fort during the war. No military conflicts with Confederates took place in the San Luis Valley.

Following the Civil War, homesteaders began to take up land in the area. Some of the new farms and ranches were made possible by bonuses received by veterans who had served at Fort Garland. As Hispanic settlements also increased, farmers and ranchers near Fort Garland found work and outlets for produce, livestock, flour, and hay at the fort.

The principal function of the U.S. Army after the Civil War was the control of Indians in the western part of the United States. In that period, the geographical arena of Fort Garland took in not only the San Luis Valley but also much of the southwestern part of Colorado, as well as the mountains east of the Valley, where raids on small settlements and remote ranches were still taking place.

When Colonel Kit Carson arrived in the spring of 1866, he was already well known to the Native Americans of the region, particularly the Ute Indians under Chief Ouray, whose special enemies — the Navajo — Carson had been instrumental in subduing during the Civil War. While Carson was at Fort Garland, Lt. General William T. Sherman visited the fort, and he, Carson, and Ute Chief Ouray succeeded in containing festering trouble.

During his brief tenure at Fort Garland, Carson enjoyed the presence of his wife, children, and acquaintances in the San Luis Valley during the warmer months, but he spent the winter at his home in Taos. Illness forced him to resign as commandant in the autumn of 1867. Shortly before his death in late 1868, however, Carson traveled to Washington to help negotiate the Treaty of 1868, which set aside land west of the Continental Divide as a large reservation for the Ute Indians.

A new cause of conflict arose when dreams of easy riches lured trespassers into the San Juan Mountains in the 1870s. The San Juans belonged to the Ute Indians under the terms of the treaty, and troops from Fort Garland were engaged in quelling trouble between Utes and the white miners. Detachments were frequently sent out on patrol during this period, until the Army established another post, Fort Lewis, on the Western Slope in 1878.

Other famous occupants also resided at Fort Garland. From 1876 to 1879, an all-black Company K, Ninth Regiment, called “buffalo soldiers,” was garrisoned there. Also, an integrated Company C, Sixteenth Infantry, was garrisoned at the fort around 1880. Arrival of the Denver & Rio Grande Railway at a station in the town of Fort Garland in 1878 made supplies easier to obtain and brought more families and visitors to the fort’s doorsteps, but, in truth, except for occasional fandangos, Fort Garland was a quiet place in the 1870s.

EVERYTHING CHANGED when the Meeker Massacre took place at the White River Agency in northwestern Colorado in 1879. Company D, consisting of “buffalo soldiers,” was patrolling in Middle Park at the time and participated heroically in a nearby scene of action.

After the trouble at the White River Agency, the entire state expected a widespread uprising by Ute Indians, and large numbers of troops were moved to western Colorado from other regions. Hundreds of troops encamped temporarily outside Fort Garland, and during that time, the fort took on the function of supply depot for the forces on the Western Slope.

The feared uprising did not occur, and the Ute Indians were thereafter confined to their reservation in southwest Colorado and to another reservation in northeast Utah. With straying Ute Indians gone, Fort Garland’s presence was no longer needed in the San Luis Valley, and it was deactivated in 1883. Troops at the fort were then transferred to Fort Lewis.

After the departure of the U.S. Army, Fort Garland was used by private citizens and businesses as a warehouse, office, and a residence while the adobe buildings inside the fort decayed and those outside it disappeared. The Fort Garland Historical Fair Association was organized in 1928 in order to preserve the property. Efforts by ranchers, businessmen, teachers, and other professional people in the San Luis Valley saved it until it was accepted by the Colorado Historical Society in 1945, and a new life began.

Preservation initially involved repair of the leaking flat roofs, adobe bricks for broken walls, and planks for rotting floors. Much of this careful restoration was performed by local people who had experience with adobe construction. Museum director Rick Manzanares points out that the recently repaired, 90-foot flag staff on the parade ground duplicates the appearance of one that was photographed there in the 1870s. Recent archæological investigations continue to reveal information that had been lost.

A new interpretive exhibit, “Saving the Fort,” occupies more than three rooms, and will be dedicated during the sesquicentennial celebration.

The Colorado Historical Society supervises restoration and operates the property, while a nonprofit group, the Friends of Fort Garland Museum, sponsors programs, provides volunteers for activities, and has established the Milton Mueller Memorial Research Library at the fort. Reenactors participate at special events to share information about military life of the period.

Fort Garland State Museum is open daily from April 1 through October 31, and Thursday through Monday in other months.

Virginia McConnell Simmons of Del Norte is the author of many regional and other histories.