Article by Columbine Quillen

Arts – March 2004 – Colorado Central Magazine

WHEN YOU MEET Keith Gotschall, any notion you might have of someone who spent twenty-two years in Boulder, such as Vegan, Sierra Club Member, Rolfing guru, or herbal tea drinker — and especially any notion you might have of a Boulder artist, such as arrogant or full of oneself — will be quickly dismissed.

Keith has a quirky smile, an unrefined wit, an engaging sense of humor, and can be charmingly silly now and again. He is also one of the finest wood turners, furniture makers, and sculptors in our region. But Keith would never tell you he was an artist unless you specifically asked, and even then he would probably answer that he makes salad bowls for a living.

Keith Gotschall was born and raised in the Midwest. According to him, his first real exposure to art was in junior high when he went to the Fort Wayne Art Institute in Indiana. Keith’s father must have noticed Keith’s artistic talents earlier, though, and sent Keith to the institute where he was exposed to all different kinds of mediums, such as pottery, etching, painting, and drawing.

Soon afterwards, in high school, Keith became a bit obsessed with wood and began taking as many wood shop classes as possible. “I took back-to-back classes in woodshop. I would go there as much as possible, I made a deal that I could go there instead of study hall.”

Keith graduated in 1980 and started reading lots of Carlos Castaneda novels and hanging out. “I knew that I had to do something for a living that made me happy and that I was good at.”

HE DECIDED NOT to go to college. Instead, he went to Washington to hike near Mount Ranier. While hitchhiking back home, Keith stopped in Boulder. “I was wearing a huge backpack on the Pearl Street Mall and no one looked at me. I had been an oddball everywhere else, and I finally fit in!”

So Keith decided to end his trip and try to make a life for himself in Boulder. He got a room at the hostel and started selling home libraries door to door. A home library is much more than just an encyclopedia set, it includes medical books, famous children’s stories, dictionaries, thesauruses, and the classics. “From hello to goodbye there was a script. They would tell you what to say to the husband as the wife went to get the glass of water you’d just asked for.” Keith hated it and decided to look elsewhere for gainful employment.

He started looking for something that had to do with wood. When he was in high school he imagined himself being a woodworker. “I had an image of a white-haired man in a woodshop. He was a happy man, and I saw myself as him.”

So Keith found a job at a furniture factory called Contemporary Comfort. They made butcher-block furniture out of 2×4’s, all glued together. It would last forever, says Keith.

“I worked all night and climbed all day.” Although Keith was first introduced to rock climbing in Indiana, he really got into it after moving to Boulder.

After a year or so, Keith decided to leave Contemporary Comfort, and he moved to Anchorage, Alaska for six months. “But I couldn’t wait to get back to Boulder. I missed everything about Boulder, like the mannequins on Pearl and 11th. They didn’t have mannequins like that in Alaska.”

AFTER RETURNING to Colorado, Keith started working at a cabinet shop. From there, a furniture designer named Don Schenk handpicked Keith to work in his shop.

“He needed highly skilled woodworkers to make his designs.” Keith became the foreman of Don’s shop. “Don was making wacky wacky stuff. Super avant-garde contemporary. My job was to kind of tone it down…. My experience there was great because I had to take someone else’s vision and make it a reality. And I was able to hone my skills because I had to come up with ways to engineer his things.”

Keith also started coming up with his own designs. After Don Schenk closed his shop, Keith got his own wood studio which he shared with his friend Glen Kalen for twelve years.

Keith describes his furniture style as very contemporary, influenced by Japanese architecture and the Italian Memphis style of furniture. The Memphis style was created by a group of architects and industrial designers led by Ettore Sottsass in the 1980s. They created furniture that was brightly colored with ceramics and glassware incorporated into the woodwork, and it was definitely cutting edge.

Keith’s own designs have strong lines that are rarely truly symmetrical, but always balanced. One of my favorite pieces is a coffee table titled “Stick, Stone, and Broken Bone.” It’s a fascinating piece. The surface area is in a triangular shape, but each leg comes up through the table. One was created to look like a stick, one like a bone, and one like a stone. Obviously, when you see this table and think of its title, you remember that old adage: “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me.” In this case, however, you can’t imagine the sticks and stones doing anything untoward, but they make a delightful conversation piece.

There are two types of hand-made furniture that Keith respects. The first may look plain from far away, but when you see it up close it’s extremely well-made and beautiful; pieces of this sort are flawlessly created products that will long outlast their makers.

The second sort of furniture he admires also has to be exceptionally well-made, but it’s also very creative and thought-provoking with a surprising cutting edge quality. Keith really enjoys seeing pieces that push the boundary and display a completely new idea.

Keith was earning a living making furniture in 1987 — almost all from referrals, many of whom became close friends — when one of his friends decided to throw away a piece of alabaster during the Boulder spring clean up. Instead, the friend gave it to Keith along with a fifteen-minute rundown on how to carve stone. And soon Keith was hooked.

Keith carved his first piece with a hammer and a screwdriver. He created a half-abstract and half-lifelike Asian face, which is still one of his favorite sculptures. After Keith made this piece he went to a marble-carving symposium in Marble, Colorado. This turned him on to carving, so he got another studio space and started carving stone in addition to making furniture.

Keith began winning art shows and museum awards, and showing in galleries. His work at the time included a commission for a statue called Transfixtion which is on 9th Street and Evergreen in Boulder.

BUT STONE JUST DIDN’T SELL as well as furniture, so Keith couldn’t put all of his energy into it. It did allow him to come up with some new furniture ideas, though. “I started doing a lot of furniture that was more three-dimensional.”

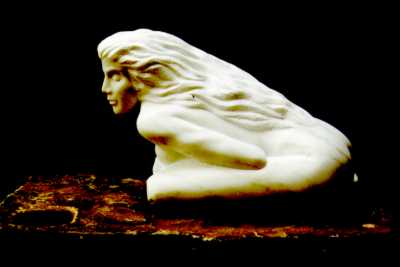

Keith’s stone sculptures are all of people, most of them of women with sensuous curving lines. Some are more basic than others, some headless and some just giving the idea of a man or a woman, whereas others are extremely polished fabrications with detailed strands of hair, delicate lips, and sinewy muscles. All have nice long lines with a focal point that makes them enjoyable pieces to look at. Unlike Keith’s furniture, which is very original and different, his sculpture is more classical in its lines and subject matter.

Keith continued sculpting and furniture making until 1998 when he started making bowls. “When I made the decision to be a woodworker in high school, I was working on a wood lathe. But I had never worked in a shop that had one.” Then he went to a friend’s shop which had a lathe and he got addicted.

“I saw him changing wood so fast, and it was so beautiful. I thought: that’s the art for me. I’m sick of being a starving artist, I did the math and figured that someone could make a good living from the wood lathe.

“My mind works really well when I’m working on something subtractive. If I have to mold something out of clay, I get a big glob and whittle it down. The lathe is subtractive.”

KEITH FOUND HIMSELF playing around on his friend’s lathe instead of doing his furniture commissions, so he started thinking about getting one for himself. In 2000 he stopped taking furniture commissions and started marketing his wood turned vessels nationally.

Keith gets most of his wood from scraps that Boulder tree trimmers don’t want, but he gets some semi-precious and precious woods from all around the world, many of them burls from the West Coast.

Although making a bowl or vessel takes much less time than a sculpture or a piece of furniture, it is still time-consuming. First Keith must go and get the wood, which involves a V10 pick-up truck and a long trailer. Keith then takes the log and uses a chain saw to shape it into a specially shaped block and then he bandsaws the corners off.

From there he mounts it onto the wood lathe, where it spins very quickly and Keith uses a variety of tools to shave it into a shape. To hollow it out, he puts the base on the lathe and then uses curved tools to hollow out the top as it spins. On many of his more expensive pieces, the opening at the top is quite small, so he cannot see what he is doing.

This is called blind turning and in order not to go through the walls he listens to the pitch that is created when the wood is spinning.

In 2002, Keith decided that he needed something new in his life. He had spent 22 years in Boulder. He wanted to buy a house and live in a quieter, less hectic place, so he moved to Salida. He now lives near Sands Lake with his two dogs, Enzo and Pepper.

Keith sells most of his work in retail shops around the country, but he also does wholesale shows and an occasional retail show. This year his work will be featured in a new book titled “500 Bowls” and he will also be at the International Museum Show in Provo, Utah.

Keith also teaches and demonstrates at several national symposiums for the 200 woodturning clubs in the country. His work can be found at his own shop, right here in Salida, and sometimes at Gallery 150 in Salida, or at the Artists Co-op in Boulder. Bowls range in price from $45 to $400; vessels from $100 to $2,000; furniture commissions from $600 to $6,000. His stone sculpture begins at $200, and prices go to $7,000. You can reach Keith at 719-539-4231.

When she’s not writing or making jewelry, Columbine Quillen tends bar at Benson’s in downtown Salida, and was recently named “Best Bartender in Chaffee County” by respondents to the Mountain Mail’s annual community poll.